Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

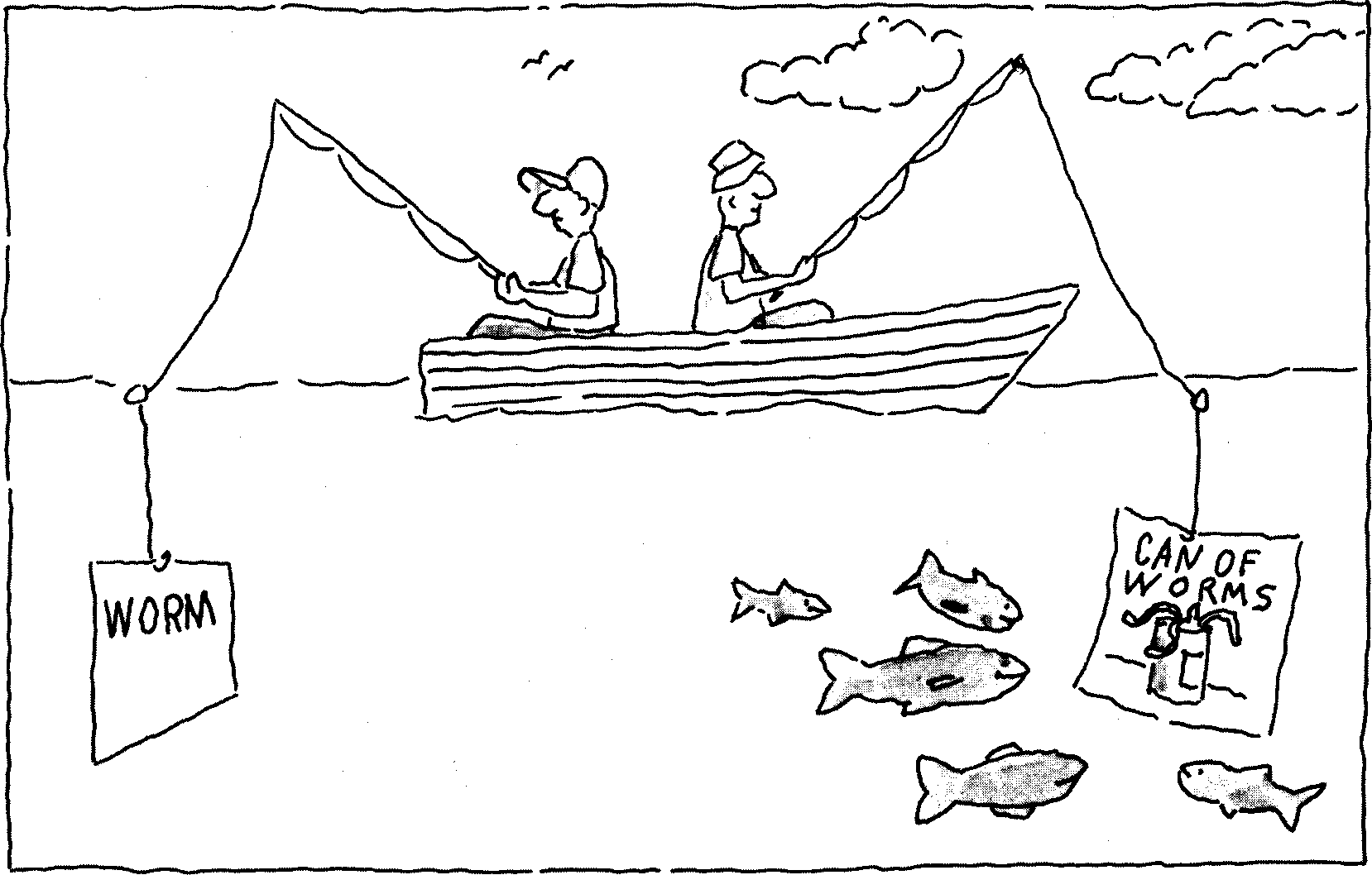

Like a fisherman catching fish with bait, a speaker lures an audience with a title that whets their appetite.

An admirer of the british writer Somerset Maugham said to him, "I've just written a novel but I can't come up with an intriguing title. Your novels have such wonderful titles - The Moon and Sixpence, Cakes and Ale, The Razor's Edge. Will you read my story and help me with the title?"

"There's no need to read your story," replied Maugham. "Are there drums in it?"

"No."

"Are there any bugles in it?"

"No."

"Well, then," advised the famous author, "call it No Drums, No Bugles."

Somerset Maugham's fan knew the pulling power of an intriguing title in selling a book. Nothing grabs the reader's attention faster than the title. Just as the title first attracts the eye of a book buyer, so the title of your speech first reaches the listener's ear when you're introduced. Like a fisherman catching fish with bait, a speaker lures an audience with a title that teases, that is, wets their appetite.

Former Toastmaster Joel_Weldon, who became a professional speaker and was awarded the Golden Gavel by Toastmasters International, titled one of his speeches, "Elephants Don't Bite: It's The Little Things That Get You." This title gave his speech a lot of mileage at a convention of the National Speakers Association, where listeners immediately perked up their ears, ready to identify those annoying "little things" that could derail them.

Another speaker titled his speech, "Pardon Me - Your Knee Is On My Chest." When the title was announced, business people in his audience were all ears, wondering "What's he driving at?" The title made them eager to know his message. This was done simply by using a metaphor (an implied comparison between two unlike things that have something in common) in the title. During the speech the audience learned that the speaker considered too much government regulation of business as painful as pressure of a knee on his chest.

Note that neither of the above titles directly tells the audience what the subject is. Are the titles then unrelated to the speeches? No. The title should not tell all. Build up suspense until the time is right to make it known.

You may think, "Isn't it better to get to the subject fast, using self-explanatory titles?" Not at all. Titles providing direct and quick identification of the subject are as ordinary and dull as labels on file folders. Lacking originality and vitality, they fail to attract attention. On the contrary, a title that arouses curiosity, such as Real Men Don't Eat Quiche, made its book a best-seller and generated such sequels as Real Men Don't Vacuum and Real Women Don't Pump Gas.

Business people use teasers to attract customers by offering something extra or free. Television and movie producers use attention-getting highlights of films, shows or newscasts before the start of a program.

For the same reasons, speakers and authors use titles to attract attention or build up suspense right from the start - before the audience hears the speech and readers open the book. Any title is justified if it piques the public's interest and implies a logical connection with the subject.

Because the results are tremendous, much time and effort are devoted to creating titles that tease. Despite its unusually long title, If Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries - What Am I Doing in the Pits? became a best-selling book. Humorist Erma Bombeck, who wrote the book, went through dozens of possibilities and hours of discussion with her agent and editors before selecting that title. She chose another long title for its sequel, When You Look Like Your Passport Photo, It's Time to Go Home, also a best-seller.

Serious books with long titles have also become popular. Among them are Harvey Mackay's Swim With the Sharks Without Being Eaten Alive, a best-selling business book on how to beat the competition. Note the title's effective imagery - It makes readers "see" themselves struggling and surviving in the sea of competition. The author's next book was another best-seller titled Beware the Naked Man Who Offers You His Shirt.

Author Robert Fulghum also wrote two books with long, intriguing titles: All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten and It Was On Fire When I Lay Down On It. Both became best-sellers, though the author thought the titles were too long. He said, "Nobody could remember the names, so people referred to them as that 'kindergarten thing' or 'fire' book."

Interestingly, both Mackay and Fulghum titled their third books with only a single term, Sharkproof and Uh-Oh, respectively. Length of title is not as important as quality, though short titles are more popular than long ones. Speakers normally prefer short titles, but also use long ones. Here are examples of actual speeches with long, effective titles:

"After You Get Where You're Going, Where Will You Be?"

"If They Pay The Fiddler, Should They Get to Call the Tune?"

How can you devise effective titles? Sometimes they emerge suddenly from your sub conscious mind. Mostly, however, you develop them with certain surefire techniques.

One such technique is alliteration (repeating the initial letters in two or more adjacent words). This rhetorical device produces a sound pattern that reinforces the meaning of the words and makes them memorable. When spoken, the words seem to echo in the listener's mind.

I don't remember the tune or lyrics of a song that was a big hit many years ago, but its alliterative title is unforgettable: "Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered." "Tart, Tingling and even Ticklish" is the alliterative headline in a successful advertisement for a soft drink.

To achieve the same impact, a professor of speech communication titled his inspirational speech, "Attitude, Not Aptitude, Determines Altitude." See how alliterative words result in a rhythmic sound pattern that attracts quick attention?

Rhyme (using similar-sounding words) also creates alluring sound effects. Believing that the adage "You are what you eat" applies to the brain as well as to the heart, muscles and bone, a physician titled his book, Eat Right, Be Bright.

Using rhyme for the same impact, another speaker used the title, "Communicate Or Suffocate" for his speech encouraging companies to respond to their critics.

Another sure way to develop speech titles that tease is to frame a question. A question invariably causes listeners to think of possible answers and look forward to the speaker's response. A wise speaker who defended large corporations thus rejected the ordinary label, "In Defense of Big Corporations" for the question, "Who Needs The Biggies?"

No matter how you come up with your speech titles, what's important to remember is to construct them in such a way as to quickly capture attention, create suspense, excite curiosity and motivate your audience to sit up and eagerly listen to your entire speech.

By Thomas_Montalbo