|

|

Great Companies, Great Investments?

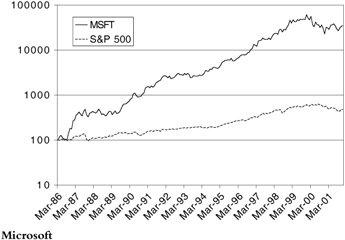

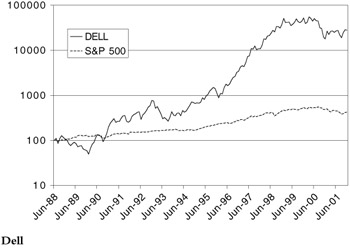

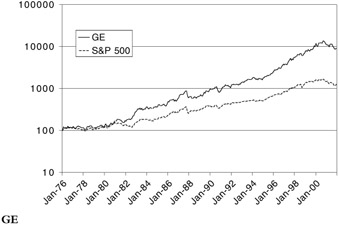

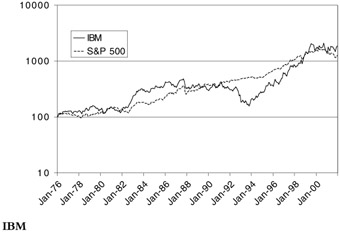

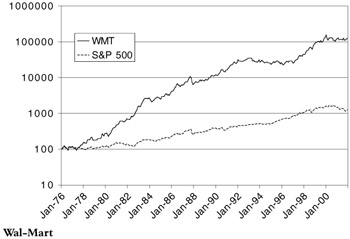

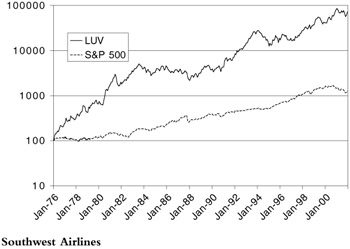

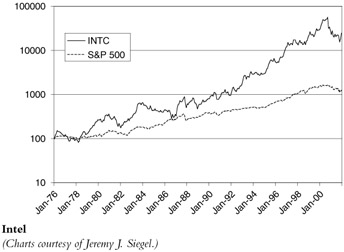

Shareholder returns are one of the most important metrics used to evaluate the performance of a publicly traded company—and, by extension, the CEO who heads it—over the long run. In their respective heydays, all of the companies run by the CEOs profiled in this resource have enriched their shareholders over the long term (as indicated by the following charts, which show the stock market performance of these seven companies).

For example, Bill Gates cofounded a company that for several brief periods, including late 2002, was the most valuable company in the world, beating out Jack Welch's GE. This is all the more remarkable given that Microsoft was one of the last of the seven companies to be founded (in 1976). The success of the company's stock made the moniker "Microsoft Millionaire" part of the business vernacular, particularly in the better neighborhoods around Seattle.

Michael Dell, of course, was responsible for the stock of the 1990s. During this decade, Dell's stock price soared an astronomical 89,000 percent. During the great NASDAQ meltdown in the early 2000s, Dell held up better than most, and, as we will see, the company increased its market share during this difficult period.

Dell was exceptional, but he wasn't a complete anomaly. All but one of the CEOs in this resource headed companies that outperformed their peers and the S&P 500 for long stretches of time in the 1980s and 1990s. Intel, Microsoft, and Wal-Mart, for example, trounced the S&P almost from the very beginning.

GE was also a star performer under Welch. When he became CEO, GE's annual revenues were about $25 billion. When he stepped down in 2001, they were about $130 billion. GE has grown at a rate of between 10 and 17 percent through all economic cycles since 1979. At the company's zenith, GE was worth some $596 billion, and its stock sold at a price-to-earnings multiple of 48, far outpacing the typical multiple for a blue-chip stock. On average, the GE's returns under Welch were double the average for the S&P.

The only company that had difficulty beating the S&P during the 1980s and 1990s was IBM. By the time Gerstner arrived at IBM in 1993, "Big Blue" was so deeply in the red that it took 5 years before IBM's returns outperformed the S&P 500, and then only by a slim margin. However, the turnaround was no small feat considering how deep a hole the company had dug for itself: In 1993, IBM had recorded an $8 billion loss, eclipsing the prior year's loss of $5 billion.

It is important to inject a note of caution at this point. While market capitalization is a useful metric for evaluating the performance of a major corporation and its leaders, there is considerable risk in getting too wrapped up in financial measures. First, these measures can be manipulated. Second, these measures are a sort of report card, a judgment on how well the organization and its leaders have played the game, but they are not the game itself.

John Bogle, one of the titans of the investing world, put it another way. Cautioning of the "perils of numeracy," he decreed "that today, in our society, in economics, and in finance, we place too much trust in numbers. Numbers are not reality. At best, they're a pale reflection of reality. At worst, they're a gross distortion of the truths we seek to measure." In light of those sagacious words, in this resource, we want to focus on the strategies and tactics that lie behind, and contribute to, financial success.

For example, although Southwest Airlines became the leading discount airline in the United States, it has never been the largest. However, Herb Kelleher takes great pride in the fact that in the three-plus decades of its existence, Southwest has been the only airline never to have a losing year (including the year following September 11, 2001). But what he is probably most proud of is that Southwest has won the airline industry's coveted "Triple Crown"—best monthly on-time record, best baggage handling, and fewest customer complaints—32 times. If you're a frequent flyer, you know that this is an astounding record.

What was going on here? Kelleher told his people not to worry about profits. Instead, he said incessantly, worry about service, and everything else will fall into place. The marketplace proved him right, and rewarded his airline. In the fall of 2002, a year after the tragic terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center—which, among other outcomes, shook the airline industry to its core—the market capitalization of Southwest was eight times that of AMR, the parent company of American Airlines.

|

|