Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Part I: Developing the Leadership Message

Part Overview

Communication is the glue that holds organizations together; it is the chief means by which people relate to one another. The aim of organizational communications is to ensure that everyone understands both the external and internal issues facing the organization and what individuals must do to contribute to the organization's success.

Communications belongs to everyone in the organization; it is not a functional responsibility limited to marketing, public relations, or human resources. Communications must become a core competency - the responsibility of everyone within the organization.

A key element of organizational communications is the messages from the leader that we call leadership communications. The chapters in Part I will show you how to develop your own leadership point of view, which you can develop into your leadership message.

At the end of each chapter are vignettes of exemplary leadership communicators. Frequently they focus on a specific moment in time when the leader used his or her communications skills to convey a leadership message in a manner that affected the vision or mission of an organization and resulted in a positive outcome.

This collection is by no means definitive. In fact, a good argument could be made that every successful leader is at heart an effective leadership communicator. The leaders presented come from all walks of life. The single unifying thread is that they all have a personal leadership style that is rooted in communications as a means of accomplishing their vision, mission, and goals as a leader for the good of their organization and for themselves as contributors to the organization.

It is worth noting that not all of the leaders included in these vignettes are world-class orators - few leaders are. All of them, however, do have an exceptional ability to communicate their ideas with words and to listen with their hearts. Each of them shows us how to lead in thoughts, words, and deeds, and in that, all are exceptional leadership communicators.

Each of the vignettes concludes with Leadership Communications Lessons that are designed to help you identify particular leadership communication strengths. You will notice that many of the lesson points occur repeatedly - with new examples, of course. This is for good reason. Good leadership communications depends upon constancy, consistency, and frequency.

Chapter 1: What Is Leadership Communications?

Overview

Of all the talents bestowed upon men, none is so precious as the gift of oratory.

Winston Churchill

Steven F. Hayward, Churchill on Leadership: Executive Success in the Face of Adversity, p. 97.

The company is a bona fide success. Its stock price is climbing. Market analysts are praising the management team. Morale is high. For a brief, shining moment, it seems that the company can do no wrong.

Then it all comes apart. Perhaps it's a new product failure, a defection of a senior leader to a competitor, or a market reversal, but suddenly the only people calling on the company are members of the media looking to find out what went wrong.

When this happens, and it seems to happen in the cycle of any successful enterprise, the company's leaders have two choices when it comes to communications: They can say nothing and hope the story just goes away, or they can speak out and work out their issues with input from key stakeholders.

Invariably companies make the wrong choice - in the face of bad news, they hibernate rather than proclaim. Worse, senior managers huddle quietly among themselves rather than speak even to employees. When this happens, communication does continue. Communication, like nature, abhors a vacuum. In the absence of word from the leader, people will create their own messages, typically in the form of rumor, innuendo, and gossip. The net result is a compounding of difficulties: Employees who could be part of the solution instead become part of the problem. Why? Because they are uninformed - worse, they are ill informed. The leader needs to get out front and tell the truth, instead of letting people draw their own conclusions. When you leave employees to draw their own conclusions without providing the proper message, they will draw the opposite conclusion from the one you want them to draw. They will automatically assume the worst, when perhaps the problem is not so grave, if it is addressed in time.

Have you ever heard something that sounds right but does not feel right? For example, when the boss says, "Our people are this company's most valuable resource," you groan because you know it's a cliché. You also know better. The boss rules by fear and looks over your shoulder constantly. Your coworkers are frustrated at their inability to make decisions. Your subordinates are fearful of losing their jobs. And the bean counters are making noises about impending job cuts. And this from a company where people are important! Could it be that there is a disconnect between the speaker and the message? Exactly! The words are not consistent with the boss's behaviors. As a result, what sounds well and good comes across as phony and false. This is an example of a situation where speaker and message do not intersect; there is a lack of credibility.

Effective messages are built upon trust. Trust is not something that we freely grant our leaders; we expect them to earn it. How? By demonstrating leadership in thought, word, and deed. Credible leaders are those who by their actions and behaviors demonstrate that they have the best interests of the organization at heart. They are the type of bosses who view themselves as supporters; they want their people to succeed, and they provide them with the help they need in order to achieve. These bosses know that they will be judged by the accomplishments of the individuals or teams who report to them, and that is why they invest so heavily in those individuals or teams.

When a leader makes a commitment to the success of individuals in order to achieve organizational goals, that leader is well on the way to earning trust. All of the leader's specific actions, such as articulating the vision, setting expectations, determining plans, and allowing for frequent feedback, are further ways of demonstrating trust.

The message emerging from a leader whom we trust is said to be a leadership message. Such a message is rooted in the character of the individual as well as his or her place within the organization. The leadership message is essential to the health of the organization because it stems from one of the core leadership behaviors - communications. Of all leadership behaviors, the ability to communicate may be the most important. Communications lays the foundation for leading others.

What Is Leadership Communications?

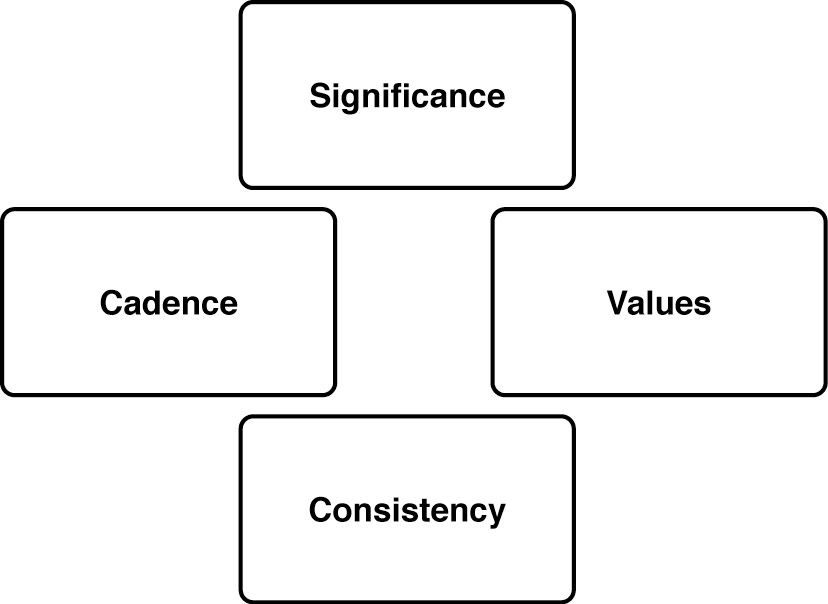

Leadership communications consists of those messages from a leader that are rooted in the values and culture of an organization and are of significant importance to key stakeholders, e.g., employees, customers, strategic partners, shareholders, and the media. These messages affect the vision, mission, and transformation of an organization. The chief intention of a leadership message is to build trust between the leader and her or his constituency. Traits of leadership communications (shown in Figure 1-1) reflect:

Significance. Messages are about big issues that reflect the present and future of the organization (e.g., people, performance, products, and services).

Values. Messages reflect vision, mission, and culture.

Consistency. Messages exemplify stated values and behaviors.

Cadence. Messages occur with regularity and frequency.

In its simplest form, leadership communication is communication that flows from the leadership perspective. It is grounded in the character of the leader as well as the values of the organization. It is an expression of culture as well as an indicator of the climate, e.g., openness, integrity, and honesty.

Purpose of Leadership Communications

There are many types of leadership communications. Each of them emerges from a leadership action that is communicated from the point of view of the leader - i.e., doing what is beneficial for the organization and the people in it. Leadership communications are designed to engage the listener, gain commitment, and ultimately create a bond of trust between leader and follower. They also do something more: They drive results, enabling leader and follower to work together more efficiently because they understand the issues and know what has to be done to accomplish their goals.

Specifically, leadership messages do one or more of the following:

Affirm organizational vision and mission. These messages let people know where the organization is headed and what it stands for. General George C. Marshall lived and breathed the core values of the U.S. Army. His penchant for preparation prepared the nation for fighting the conflict it did not want to fight - World War II. By giving detailed briefings to Congress, developing a cadre of superior officers, revamping military training, and supporting President Franklin Roosevelt, Marshall mobilized the armed forces to go overseas and defeat the tyrannical powers of the Axis. And later, as secretary of defense, he helped Europe recover economically, socially, and politically through a comprehensive aid program that eventually bore his name, the Marshall Plan.

Drive transformational initiatives, e.g., change! These messages get people prepared to do things differently and give the reasons why. Rich Teerlink, former CEO of Harley-Davidson, spent much of his time at the helm enkindling a passion for the company among dealers, owners, and employees. Part of this passion was rooted in the need to transform Harley from an old-line manufacturer into a modern enterprise in which employees shared in the voice and the vision.

Issue a call to action. These messages galvanize people to rally behind an initiative. They tell people what to do and how to do it. Rudy Giuliani, as mayor of New York City, inherited a city whose citizenry accepted as fact that high crime, social service failures, and city hall ineptitude were part of the social contract. Through a combination of daily meetings with city agencies, public proclamations, and holding people accountable, Giuliani reduced crime, reinvigorated social agencies, and raised citizens' expectations for public servants' performance. Giuliani also prepared himself and his government for prompt response to the horrible events of September 11, in which New York City served as a proud example of civic and individual and collective heroism, stoicism, and eventual healing.

Reinforce organizational capability. These messages underscore the company's strengths and are designed to make people feel good about the organization for which they work. Katherine Graham, publisher of the Washington Post, relied upon the people in her organization to build a world-class news organization. Her public comments in the face of the publication of the Pentagon Papers, the Watergate investigations, and nasty labor struggles at the paper demonstrated her undying commitment to the paper.

Create an environment in which motivation can occur. These messages provide reasons why things are done and create a path of success for people to follow. They also describe the benefits of success, e.g., a more competitive organization, more opportunities for promotion, or increased compensation. Joe Torre, manager of the New York Yankees and winner of four World Series in his tenure, believes that everyone on the team has a role to play. His quiet demeanor, coupled with supportive words and actions, has created an environment in which players feel that they can achieve and strive to do so.

Promote a product or service (and affirm its link to the organization's vision, mission, and values). These messages place what the organization produces within the mission, culture, and values of the organization; e.g., we create products that improve people's lives. Shelly Lazarus, former CEO of Ogilvy & Mather, a leading advertising agency, makes her living using communications to promote the virtues of internationally known brands like IBM and Ford. She applied the same commitment to promoting her agency's brand as a place where exceptionally talented people can succeed.

Examples of Leadership Messages

The style of leadership messages varies according to their purpose. Here are some examples:

Vision

Our challenge is to complete this project by year's end. When the project is complete, we will have the exciting new product our customers have been asking for. This product will enable them to work more efficiently, and it will enable us to grow our business profitably.

Transformation

The challenges in the market dictate that we do things differently - internally in the way we operate and externally in the way we serve our customers. The changes we are calling for will not be easy, but they will be necessary. Yet we must learn to embrace change. Instead of viewing change as something to be feared, we must leverage its power and capitalize on the new opportunities it will bring us.

Calls to Action

The days ahead will call for critical thinking and timely action. We need all of us to pull together as a team. I am asking each of you for your support as we go forward together in our quest to create a better future for us and for future generations.

Expectation

I view my leadership role as one of supporting our team. I expect everyone on our team to support our collective objectives and work cooperatively with one another. I expect people on our team to think and problem-solve for themselves. When you encounter obstacles that you cannot resolve, I expect you to bring them to my attention. If you stonewall and hide problems, you will be asked to leave the project.

Coaching

Your enthusiasm for this job is admirable. I would like to make a few suggestions for ways in which you might improve your performance.

Recognition

You have done an outstanding job on this project. I want you to know how important your contributions are to our team. Bravo. Well done!

You can probably think of many more examples yourself. These are just for starters. The importance of leadership communications is the seminal role it plays in enabling the leader to succeed.

Enabling Listening

Communications, as Peter Drucker has written, is less about information than it is about facilitating kinship within the culture.[1] Employees must feel that they have a stake in the organization and its outcome. The ownership stake is initiated, nurtured, augmented, tested, and fulfilled through leadership communications. It is absolutely critical for the leader to facilitate two-way communications, specifically allowing feedback in the form of ideas, suggestions, and even dissent. Too often communications within organizations is interpreted as being one-way from the top, that is, information is disseminated in neat packages like commercial messages. In fact, leaders would do well to emulate one aspect of the advertising process, and that is the relentless search for information in the form of consumer research. Advertisers want to know what you think of the message. Leaders can do the same. It's called listening.

Reiterating Leadership

Communicating the leadership message over and over again in many different circumstances lets employees come to a better understanding of what the leader wants, what the organization needs, and how they fit into the picture. In time, leader and followers form a solidarity that is rooted in mutual respect. When that occurs, leader and followers can pursue organizational goals united in purpose and bonded in mutual trust.

The chief aim of organizational communications is to ensure that everyone understands both the external and internal issues facing the organization and what individuals must do to contribute to the organization's success. Communications belongs to everyone in the organization; it is not a functional responsibility limited to marketing, public relations, or human resources. Communications must become a core competency - the responsibility of everyone within the organization. Toward this end, management must establish a climate that ensures that employees feel free to express their ideas and concerns. At the same time, management must be clear in its expectations for individuals, teams, and the organization. Management must also structure its communications in ways that are meaningful and in keeping with the culture of the organization.

Winston Churchill - The Lion who ROared for His People

Winston Churchill wrote this about becoming prime minister in May 1940 during what some have called Britain's darkest hour:

As I went to bed at about 3 a.m., I was conscious of a profound sense of relief. At last I had the authority to give directions over the whole scene. I felt as if I were walking with destiny, and that all my past life had been but a preparation of this hour and for this trial. . . . I thought I knew a good deal about it all, and I was sure I should not fail.[2]

Soon enough, Churchill would refer to this period, in which Britain, her skies defended by men in their twenties and her people bloodied, battered, and bruised by nightly bombardments, stood alone against Nazi Germany, as her "finest hour." It was a phrase that historians would later use to describe his performance as leader.

How did he do it? His own words just cited give a good indication. He knew a "good deal": His two stints as First Lord of the Admiralty, plus his time as minister, had given him insight into how the military and government must coordinate their efforts. He had the "authority to give directions": He had led men in battle, in government service, and in Parliament. He was one with "destiny": As a historian and an avid reader, he measured himself against the legacies of great leaders in wartime. He was confident: "I was sure I should not fail." As historian Geoffrey Best amply illustrates in his one-volume meta-biography, Churchill had been preparing for this challenge for his entire life: as soldier, parliamentarian, minister, historian, and journalist.

A Natural Communicator

What Churchill's words do not say, but imply, is this: He was a born communicator. He knew how to describe a scene, present a point of view, and tell a good story. He also, as his biographer Geoffrey Best writes, put his audience at the center of the action. During his speeches and broadcasts of the war years, he positioned the British people at the center of the world; he spoke to them as actors on the world stage.[3] By so doing, he made them feel a sense of importance - or, as we would say today in management, encouraged them to take a position of ownership of the issue. When this occurs, people have a sense of their own destiny; during any great event, such as a war, people may feel a sense of insignificance, a sense that they have no ability to affect the outcome. Churchill's speeches counteracted that sentiment as he spoke again and again of the individual contributions of the British people at home or abroad.

Churchill made certain that his message got through. His speeches in Parliament were of course widely covered. And when he took to the airwaves, people stopped what they were doing, whether at home or at work, to listen. He courted the press barons of his day, in particular Lord Beaverbrook, making him a member of his Cabinet.

Churchill also made frequent use of memos, or, in his parlance, "minutes." Reading samples of them, one gets the feeling that he was totally immersed in the activity, quick with suggestions or requests for follow-up.[4] His memo writing enabled him to use his pen when he did not have the luxury of face-to-face communication. These memos also documented what occurred and what follow-up actions resulted. Again and again, Churchill insisted on written communications for precisely this reason: He wanted to be in the loop on important decisions.[5]

Brutal Honesty

Churchill was direct and straight with his people. He did not hide the dangers that faced the island kingdom in the dark days of 1940. As he told the House of Commons in his first speech after becoming prime minister,

I would say to the House, as I said to those who have joined this government: "I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat."

We have before us an ordeal of the most grievous kind. We have before us many, many long months of struggle and of suffering. You ask, what is our policy? I can say: "It is to wage war, by sea, by land, and air, and with all our might and with all the strength that God can give us."[6]

Ever the realist, Churchill knew that he could not simply deliver a challenge. He had to sketch his vision of the end - a note of inspiration in a time of desperation.

You ask, what is our aim? I can answer with one word: It is victory, victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror, victory, however long and hard the road may be; for without victory, there is no survival. Let that be realized; no survival for the British Empire, no survival for all that the British Empire has stood for . . . and I say, "come then, let us go forward together with our united strength." [7]

With that speech, which is brief by Churchillian standards, he rallied Parliament, which had not been favorably disposed toward him. As he closed, he, along with the House, was in tears. This speech was also the beginning of the metaphysical union between Churchill and the British people that would endure throughout the war. As philosopher Isaiah Berlin essayed,

The Prime Minister was able to impose his imagination and his will upon his countrymen . . . precisely because he appeared to them larger and nobler than life and lifted them to an abnormal height in a moment of crisis. [In doing so] it did turn a number of inhabitants of the British Isles out of their normal selves [and capable of heroism].[8]

"Flying Visits"

One way in which Churchill maintained unity with his people was by meeting and mingling with them. From his earliest days, he had had a love of action. As prime minister, he took it upon himself to make frequent "flying visits" to the front in North Africa or Europe, to America to press British interests with the Roosevelt administration, and even to Moscow and Yalta to negotiate Soviet support during the war and stem Soviet aggression in the postwar era. Another kind of flying visit was to his own people. He visited the London Docklands area, which was heavily bombed during the Blitz, and even risked his own life when he stayed until nightfall and was caught in the middle of a raid.[9] Never lacking in courage, Churchill believed it was important that he both see the damage firsthand and be seen as a leader who was one with his people.[10]

Leadership Query

One of the methods Churchill used to exert a measure of control, which also helped him to come to grips with issues, was interrogation. Military analyst Eliot Cohen writes that Churchill did not just ask a question and then forget it; he followed up with "a relentless querying of their assumptions and arguments, not just once but in successive iterations of a debate." While at times this drove his generals and aides crazy, it did keep Churchill informed and his direct reports on their toes. Churchill, unlike other wartime leaders, was both a former military officer and a historian. So while his questions may have irritated his generals and aides, and while at times he did go too far, Churchill's breadth of knowledge lent him a greater degree of credibility in military matters.

One story among many illustrates Churchill's insight as well as his willingness to ferret out answers. Upon learning that regimental patches (a form of military insignia) were no longer being issued to British troops, Churchill investigated. The Army Office said that it was cooperating with the Board of Trade, which had forbidden the patches as an unnecessary use of cloth. In reality, the Board of Trade had no problem with the patches; the Army was making excuses for its "wildly unpopular decision." The real issue, as Churchill understood, was not a patch of cloth; it was esprit de corps. British Tommies identified with their regiments; to deprive them of this distinction would adversely affect morale. The regimental patches returned.

Unlike lesser leaders, Churchill expected his generals to disagree with him. He did not want yes men; he wanted commanders who could think and plan for themselves.[11] And this is why he had such fractious relationships with his chiefs of staff. By repeatedly questioning their decision making, Churchill assured himself, and by extension the British people, that their military strategies were sound. Mistakes were made, of course, but Cohen believes that Churchill's hands-on approach, chiefly by virtue of his communications, was the proper course.[12]

Leadership Pragmatisim

Churchill was a pragmatist. He was elected to Parliament as a member of the Liberal party, and he was a minister in David Lloyd George's cabinets before and during the First World War. When the fortunes of the Liberals declined, he declared for the Conservatives, his father's party, and in the late 1920s became chancellor of the exchequer, again something his father had been. His party switch was opportunistic, of course, but it was born of his need to be in the thick of the action, to be of service, to be doing something of value and merit. As a result of his opportunism, he was widely disliked throughout his career by those of his own class as well as by party loyalists. As his biographers point out, it was his service as prime minister that endeared him to the people. Prior to that, all too often he had been regarded more as a busybody, an opportunist, and a self-promoter.

Contrary to his image as a tough leader, Churchill was repeatedly kind to his adversaries once he had defeated them. He kept his predecessor, Neville Chamberlain, whom he had criticized for his appeasement strategy in dealing with Hitler, in his War Cabinet. In part this was due to the fact that most Conservatives favored Chamberlain over Churchill; nonetheless, Churchill was generous to his political enemies after the battle was won - something his adversaries were not throughout his long career in politics. (When Chamberlain died in November 1940, Churchill gave a eulogy for him in the House of Commons.) [13]

Churchill put his own perspective on his wartime leadership when he said to the House of Commons in 1954, "It was a nation and race dwelling all around the globe that had the lion heart. I had the luck to be called upon to give the roar." Never have the forces of freedom been blessed with such a roar!