Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California - Westside Toastmasters on Meetup

Ensuring Organizational Feedback

Effective communications is a two-way street. All too often leaders spend the bulk of their time on crafting a message without stopping to listen to what people are saying about it. It is imperative that leaders provide avenues through which followers can voice their opinion of a leadership message as well as provide additional ideas that reinforce organizational values.

In this way, as mentioned previously, leaders enable the employees to take ownership of the idea. When you ask for feedback, you are saying, "We care about you, and we want your ideas." In return, the employee will feel a sense of obligation to contribute. In effect, asking for feedback is a kind of call to action.

The U.S. Army has a policy of expecting junior officers to challenge senior officers' opinions on matters related to the health and safety of the troops. During After Action Reports, the postmortem reviews of military exercises or actions, junior officers are encouraged to speak up and say how things might have gone differently. Why? Because the Army views AARs as learning tools. Continuous improvement will occur only when people can speak their minds. This does not mean that senior leaders need to agree; it simply means that they must listen. The same rule should apply in the civilian sector.

Implementing a Plan for Soliciting Feedback

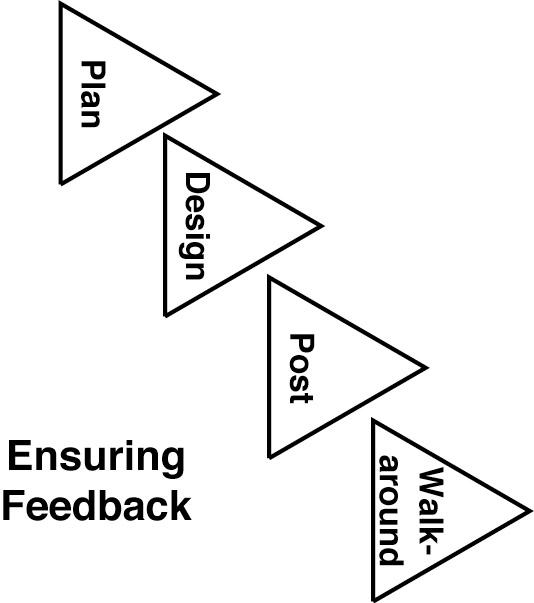

Leaders need to understand that feedback will happen spontaneously. It is part of the passive communications environment discussed earlier in the chapter. People will respond to the message in any number of ways: discussing it with colleagues, talking to their friends about it, or sometimes speaking to the media (off the record, of course). What the leader needs to do is to ensure an outlet for the feedback. You can do this in several different ways (see Figure 4-3).

Plan for feedback. When you develop the communications plan, build a feedback loop into the process. As part of the planning process, let people in the organization know that you will be soliciting feedback and sharing the results of that feedback with them.

Design a meeting around feedback. Encourage team leaders to hold feedback meetings. The only action item for such a meeting will be discussion of the issues. You can even provide a "meeting in a box" toolkit with questions to help managers who are unfamiliar with the feedback process to get employees to talk about the issues.

Post the feedback you get on your web site. Select sample emails and post them on your web site. Omit the names of respondents; this protects the respondents' confidentiality as well as keeping people from focusing on the personality rather than the expression of the idea.

"Walk around" to get feedback. Get out from behind the desk and walk the halls. Find out what people are thinking. A great way for leaders to do this is to make a habit of dining in the cafeteria at least once a week.

Ensuring that Feedback Is Heard

Many leaders say that they want feedback and even ask for it; the problem is that they never seem to find the time to respond to it. And let's be fair, leaders have many to-dos. The leader of an organization with hundreds or thousands of employees cannot be expected to respond to every email. What he or she can do is assign people to screen the mail and provide some response, and also respond personally to certain messages.

Another good tactic is to hold a webchat, which is an online question-and-answer session between leader and employees over a secure Internet connection. One way to begin the session is to have the leader sum up what he or she has heard so far and then open the session to questions from employees. (Hint: It never hurts to prepare a few questions in advance in case respondents are slow in submitting questions.)

Yes, Bad News Here

Leadership brings with it isolation. As a leader moves higher up in an organization, he or she loses touch with the people at the grassroots level. Ensuring that feedback channels are kept open helps the boss stay in touch. But leaders need to do more. They need to establish ground rules that say that it's okay to deliver "bad news." Enron is a classic example of a company where the delivery of bad news was punished; people who asked probing questions, questioned decision making, or reported bad news were not promoted, and in some cases were asked to leave the company.[8] Enron is not an isolated example. Many companies do this, and in the process they isolate their leaders from the truth. Leaders themselves can make it clear that they want the unvarnished facts. Abraham Lincoln was constantly nagging his generals to give him the truth, especially when the Union was losing. Successful business leaders do the same.

Let's face it, isolation at the top is often the leader's own fault. He or she fails to meet and mingle with front-line supervisors or talk to customers. Worse, the leader promotes those who tell him or her what a good job he or she is doing and are always ready with the positive spin. Some leaders shun candid speakers because they fear that listening to them will reflect poorly on their leadership. In fact, the opposite is often the case. When small problems go unnoticed and untreated, they can mushroom into huge issues, even catastrophes. Colin Powell has said that if a leader is not hearing bad news, something is wrong. "The day soldiers stop bringing you their problems is the day you have stopped leading them. They have either lost confidence that you can help them or concluded that you do not care. Either case is a failure of leadership."[9]

The Challenger disaster is one such example. The engineers at Morton- Thiokol knew that the O-rings in the booster rockets were not certified to withstand freezing temperatures. Yet when NASA pushed for a launch in near-freezing weather, the engineers had no ready way to communicate their knowledge. The "no bad news" culture that permeated the space program at that time thwarted open dialogue between the suppliers' engineers and program leadership. All the engineers could do at launch time was watch in helpless agony as the Challenger's booster exploded in midair. In contrast, years earlier, Gene Kranz, the legendary flight control director of the moon flights, was in the room when Apollo 13 suffered an oxygen tank rupture en route to a lunar orbit. The astronauts in the spacecraft, together with the innovative flight team on the ground, devised a solution that brought the astronauts home safely. This culture of cooperation is an example of Kranz's leadership style; leaders and doers operated in an environment where information was shared openly.

Getting Feedback One-to-One

Getting honest feedback from direct reports is no easy task. We humans have a strong instinct for self-preservation, so we don't bite the hand that feeds us. Therefore, when the boss asks us what we think of something coming from the top of the organization, our first reaction is to be positive. We don't want to say anything that will put our careers in jeopardy. Such a reaction may be human, but it is not healthy. We owe it to our leaders to give them honest feedback, but our leaders need to set the ground rules—i.e., they need to ensure that what is said to the leader will be kept in confidence and will not be used against the employee.

So how do leaders get feedback? First, they need to put people at ease. Make it clear that candor is the operative process. Demonstrate the benefits of honesty by accepting feedback in the spirit in which it was delivered. Next, leaders need to ask for feedback on a regular basis. You want to get people in the habit of expressing their ideas. No leader should expect to get instant candor, but when someone speaks out and does not suffer for it, others will begin to do likewise and may be more forthcoming. Still, the leader needs to work at getting feedback. Often what is not said may be the most revealing truth of all.

Of course, we need to separate the deliverer of bad news from the creator of the bad news. When people make a mistake, there will be consequences. Reporting the bad news, even when it involves your mistake, is a form of leadership; it's called taking responsibility for one's own actions. Merely reporting that news, however, should not reflect negatively on the messenger, if it's delivered in a way that is intended to keep the boss informed so that she or he has the information needed to take corrective actions. Leaders do not want to create a culture of tattletales; rather, they want to create a culture in which people can speak openly and share information in ways that reflect the credibility of the information and the organization.

[8]John Schwartz, "As Enron Purged Its Ranks, Dissent Was Swept Away," New York Times, Feb. 4, 2002.

[9]PowerPoint presentation, "Leadership Lessons of Colin Powell," probably adapted from Oren Harari The Leadership Secrets of Colin Powell.