Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California - Westside Toastmasters on Meetup

Chapter 12: Leader as Storyteller

Overview

I've been an orator really, basically, all of my life. Since I was three and a half, I've been coming up in the church speaking. . . . I've spoken at every church in Nashville at some point in my life. You sort of get known for that. Other people were known for singing. I was known for talking.

Oprah Winfrey

Janet Lowe, Oprah Speaks: Insight from the World's Most Influential Voice, pp. 15-16.

The atmosphere in the room was tense. For the men in the room, what would happen next could mean a pat on the back on the way up the ladder, or a kick in the backside on the way down. It was an army briefing room. The man to be briefed was a legend, a soldier's soldier, General Creighton Abrams. For one young man in the room, a major, it was a chance to glimpse up close the legendary tank commander who had helped rescue the 101st Airborne at Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge. The intervening years had not mellowed the old soldier; he was now commander of all forces in Vietnam. One by one the more senior officers stood up and made their briefings. There was no reaction from the general. Finally it was time for the major. He stood up, strode to the front of the room, and itemized unit strengths and weaknesses battalion by battalion. He did it without notes; he had only a pointer and some charts. When he finished, Abrams grunted and left the room.

Another soldier followed him out and returned minutes later with a big smile. "Abe's happy," he said. The major asked how he could tell. "For one thing, he wanted to know, who's that young major?"

The major was one that all of America would know two decades later: Colin Powell.[1]

That's a great story about an American hero!

Now imagine that a leader who was recounting this event simply stood up and said, "Once upon a time a young soldier gave a briefing to a general and made a positive impression."

True, but bor—ing! By the second line, members of the audience would be checking voicemail with their cell phones, answering email on their PDAs, or catnapping. They would not be engaged. Why? Because a clinical rendition omits context and character. It is from those two elements that good stories emerge.

Context and character reverberate throughout the communications of effective leadership communicators. Rosabeth Moss Kanter includes many stories from the front lines of change; if you just read the stories from her many books over the past two decades, you can get a good sense of the change that American management has experienced in recent times. Colin Powell is a good stump speaker, filling his speeches with stories from his life as well as stories of people he has met along the way. Harvey Penick's coaching method, which is reflected in his books, uses stories to illustrate points about the game of golf, as well as points about life in general. Mother Teresa told stories about the work in her mission to interviewers as well as to famous and not-so-famous people as a means of encouraging people to help the poor, not only in India but in their own communities.

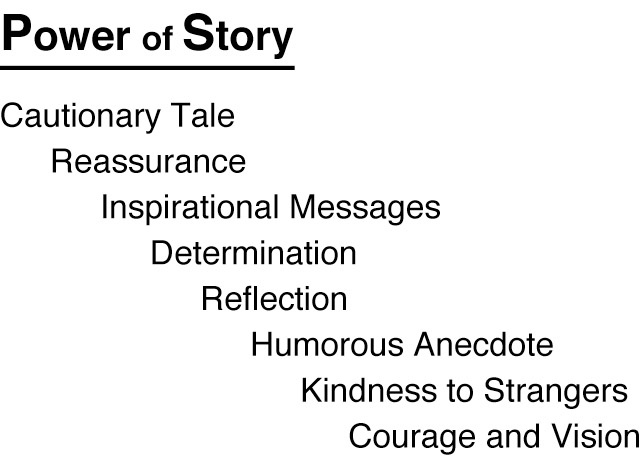

Through storytelling, leaders can frame a current experience through the prism of context and character—their own or someone else's. Stories can be used to uplift the spirit, to caution the unwise, to provide insight into experiences, and even to laugh at a situation. Leaders who learn to tell stories are leaders who are innately aware of the human condition, an insight that prepares them to lead others (see Figure 12-1).

[1]Colin Powell with Joseph E. Persico, My American Journey, pp. 131-132.