Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 4: Releasing Potential Energy

Overview

Every situation in our lives has some sort of potential energy that is waiting to be discovered and tapped into. This can take the form of tension or unresolved conflict: 'I want this, but I also want that.' Merely focusing on the 'this' or the 'that' does not make for very exciting possibilities. But discovering and releasing that potential energy can lead to some very high-voltage results indeed. This chapter is about finding the hidden conflicts that motivate us all.

In physics, 'potential energy' is stored energy, energy that is waiting to be released. A tensely coiled spring is just waiting to explode outward and transform its potential energy into kinetic energy.

We all innately long for the resolution of tension. Seeing a coiled spring, you know that it will eventually burst forth; in a suspenseful movie, you know in a quiet scene that something or someone will pop out and scare the life out of you; the last chords of a symphony lead inevitably to the tonic chord, to provide a satisfying conclusion.

Melachy Welsh, a mentor of mine, teaches that the energy arising from tension is the force that moves society forward. All of us have needs, appetites, duties, and responsibilities that drive us through each day - from short-range issues ('What will I have for lunch?') to long-range ones ('How can I make my family's life better?'). These needs often pull us in a number of directions at once: I want to buy groceries for my family according to my own personal standards, and yet I'd like someone else to do the grunt work so that I can spend my time elsewhere. It seems that you can't have it both ways - you have to either invest a substantial amount of time in grocery expeditions or turn over the responsibility to someone else and take the risk that the task won't be completed in a way that satisfies you.

We'll come back to the idea of potential energy and how to release it, but first, let's take a broader view. You'll see how Thomas Edison's 'turn it upside down' motto applies to the world of brand development.

New and Improved

In the olden days, innovations that filled consumers' unmet functional needs were enough to build a major brand. Floor wax that dissolved the old wax and applied the new in one step, for example. Shampoo and conditioner with vitamins to make your hair shiny and strong. Paper towels that soaked up spills faster than the competition. But in today's marketplace, most of those important needs are already filled by a brand, and usually by more than one.

We have a huge proliferation of choices in every category. When I took my adolescent son shopping for deodorant for the first time, his eyes bugged out of his head when he looked at the hundreds of choices. Antiperspirant? Deodorant? Gel or stick? Which scent? Which brand? In the end, he'll choose the brand that his classmates say is cool. Or the one that has the satirical ad on Facebook.

Unfortunately, the brand teams that create those products focus the majority of their innovative efforts on creating superior formulations for their products.

What they don't realize is, their target audience is looking for that and for something more.

Exercise

Why Do You Buy What You Buy? - Part One

Take out your last grocery list or receipt and write down all the brand-name items you purchased. Then do the same with the last brand-name products you picked up at the mall.

What made you buy what you bought, compared to the alternatives that you could have bought?

What was it about that brand of juice, that style of sneakers, those headphones, that kind of perfume or cologne?

How much of your selection had to do with a formulation or some technical feature or a discount price, and how much had to do with an image or an idea?

Sometimes the rational reason is the intellectual alibi for the emotional satisfaction. Pick one of the products you bought and imagine: If that brand were a world, what would that world be like? Where would it be located? What time of day would it be? Who would inhabit it? Then ask yourself, is that world a place you'd like to live? To visit? If so, maybe there's more to your brand choice than meets the eye.

Brand First, Product Second

Grown-ups tend to sort things first by product class and then by brand. In other words, when we need new athletic shoes, we may look for cross-trainers first, then we look at brands and offerings within that category. By contrast, kids today seem to sort these choices by brand first, and then product. So they'll choose the Nike brand first, then look for the type of product they need.

We are moving toward a population of consumers who process the world primarily in terms of a brand's voice, personality, and world. Rational, tangible product attributes are still important, but less as a way of distinguishing one brand from another; instead, they are important in terms of how they bring a brand's world to life.

Marketers whose products succeed create innovative brand worlds first, then deliver those innovative brand worlds with new, tangible product attributes that pay off the brand imagery. Those tangible attributes might be packaging, fragrance, or distribution-not the traditional kind of innovation that's initially dreamed up by R&D during the product's formulation.

The Traditional Innovation Process

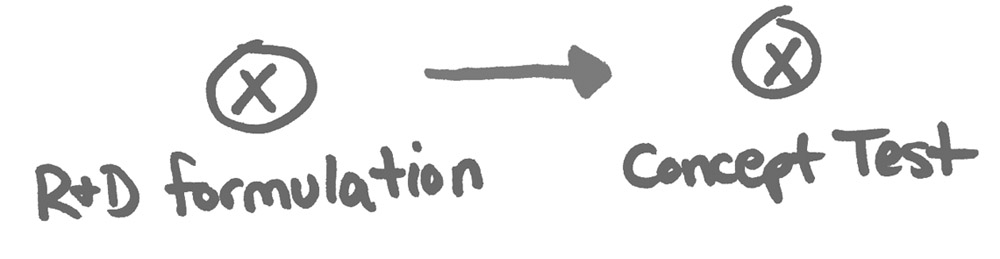

Traditionally, product innovations came from R&D people, who made interesting new formulations aimed at filling important and unmet needs in a category.

Then the marketing department would describe those product features by writing a sentence or two about each and printing that information on a card. The marketing research people would bring a bunch of those cards to consumers and record which features they liked the most and which they said they would be most likely to buy.

Finally, the marketing people would take the winning concept and give it to the ad agency, which would figure out the appropriate brand voice, personality, and world.

The problem with this process is that in today's marketplace, it is inadequate to the task. It generates ideas that consumers will say are 'great for camping' - in other words, things that seem clever but are not really relevant to everyday life (which is the Kiss of Death Assessment for any new idea).

In today's marketplace, where there are dozens of kinds of sparkling water to choose from, a product innovation that begins in the lab is unlikely to make enough of a difference to succeed. Back to my son in the drugstore eyeing the deodorant choices. A fancy new formula that keeps him 20 percent drier just isn't going to be enough to get him. Something that's cool, a brand name that conjures up an attitude he aspires to, a graphic that evokes a world of imagery that captures his imagination . . . those things will be. Of course, the product has to work, too. Image alone is also not enough.

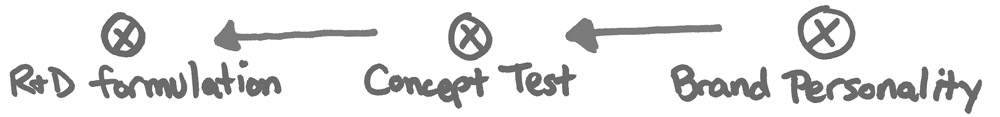

A New Innovation Process

Because today's consumers are moved by a brand's voice, personality, and world as much as they are by specific product features, the innovation process must begin with the end in mind. We begin by assessing what brand imagery is missing from a category, then we drill down and ideate tangible product features that bring that imagery to life, and then we hand that information to R&D so that it can make prototypes. We've set the traditional process on its head.

But how do you know where exactly to begin? This is trickier than it sounds. In order to work, the imagery needs to resonate with consumers. It needs to touch them in a way that is meaningful to them and in a way that is fresh and interesting.

The key here is to tap into the potential energy of a situation. That energy comes from the tension created by the conflicts - the paradoxes - that are part of everyone's daily life.

Oh, Well

These consumer paradoxes tug at us every day, so often that we don't even consciously notice them. Every decision we come to, every action we take, requires a trade-off. We spend our mental energy sorting through alternatives, doing 'lesser-of-two-evils' balancing. Most paradoxical situations are shrugged off with 'oh, well' - that's the way it is; life isn't perfect; you can't always get what you want. Mostly, we choose to complain rather than create.

The vending machines on campus stock only junk food, but what the students need and want are fresh fruits and veggies and low-cal protein. Oh, well.

Babies scream on airplanes when business travelers want peace. Oh, well.

A challenging career demands the investment of time, as does a satisfying home and family life. Oh, well.

Paradox exists at many levels, from the product-focused ('I want clean carpets, but I don't want to spend the time and energy vacuuming') to the spiritual / psychological ('I want to be passively entertained, and I want to be spiritually nourished').

In other words, it is the intersection of needs that creates potential energy and the possibility of creating an interesting resolution to a problem. If you simply identify a need as a flat statement ('People want to be healthy') - well, that leaves a thousand directions open and has little energy. There is no particular option to home in on, and there is not enough grist for the idea mill.

However, if you think of the issue as 'People want to be healthy, but they don't want to change any of their habits,' that ripens and focuses the challenge. If you imagine these desires as arrows moving perpendicular to each other, the point of intersection is where the potential energy lies. Starting there, you can begin thinking of a solution that solves the problem in each direction.

Consumers are dealing with perpendicular arrows in every area of life-holding onto conflicting desires or expectations or demands simultaneously. Products that make a real impact on the marketplace don't just resolve tensions and conflicts, they resolve those tensions and conflicts in a unique way. A high-voltage idea releases the potential energy, and there are sparks, light, and heat.

Acknowledge The Conflict

Instead of trying to ignore the conflicting desires in a situation, successful brands acknowledge the paradox and resolve it in a fresh and interesting way.

Target: I want to be stylish and hip, but I don't want to spend a lot of money.

Before Target reinvigorated its image, shopping at a discount retailer wasn't something to be ashamed of, perhaps, but it certainly wasn't anything to draw attention to. Many stores radiated an air of 'you don't want to be here, and we don't either, but at least you're saving a couple of bucks.' Target identified this conflict and removed the inferiority complex from its stores and its product lines.

Nike: Participating in sports is exhilarating, but I'm out of shape and tired, so I'll watch somebody else do it on TV.

Nike has taken on the challenge of making the difficulty of exercise its selling point: 'Just do it,' even though it's tough.

Exercise

Creativity From Conflict

For each of the following conflicts, come up with a high-voltage idea for a product or service that resolves the conflict in a unique way.

'I want to be happy and comfortable in my home, but I'm very concerned about the environmental effects of manufacturing and using certain products.'

'I want to be able to enjoy popular culture with my children, but I'm afraid of exposing them to violent images.'

'I want to do work away from the office, but I don't want to sit home all day, either.'

'I want to start my own business, but I don't have enough money to hire a support staff.'

'I want to be able to eat at restaurants with my friends, but I'm limited by my dietary restrictions.'

Again: Logic Versus Energy

A single product can address more than one conflict. For example, a consumer who is shopping for skin-care products is unconsciously trying to resolve paradoxes such as:

I want it fast, but I want it to be exactly right for me.

I want to be in control, even when someone else is the expert.

I love my best self, but I'm afraid it's not enough.

The common element in these paradoxes is that they are emotional; they deal with our vulnerabilities and anxieties. As we go through the day, we make choices based on instincts and feelings that we may barely understand; we aren't aware of these paradoxes on a conscious level, but they still hold us in their grip.

Again, this harks back to listening for logic versus listening for energy. Logic dictates that consumers will always buy the most efficient product - the product that is the most nutritious, that cleans windows without streaking, that gets the best gas mileage. All things being equal, they will purchase the least expensive alternative.

But of course, transactions (dynamic ones) aren't based only on logical reasons. If they were, we'd all make our coffee at home, we'd wear sensible shoes, and generic store brands would be the only things sold on supermarket shelves.

A successful product has something more, something that satisfies a buyer emotionally, fulfilling more than one need. The consumer won't necessarily be able to put her finger on just what led her to make her choice, but the magnetic attraction is there just the same.

Exercise

Why Do You Buy What You Buy? - Part Two

Return to the first part of this exercise and look at your list of explanations for buying the products you bought.

Now that you know more about the magnetic attraction of potential energy, zero in on some of your favorite purchases and identify the internal conflicts and paradoxes that each of these products addressed for you.

Climbing Down The Benefit Ladder

Let's take a step back to the traditional way of doing things.

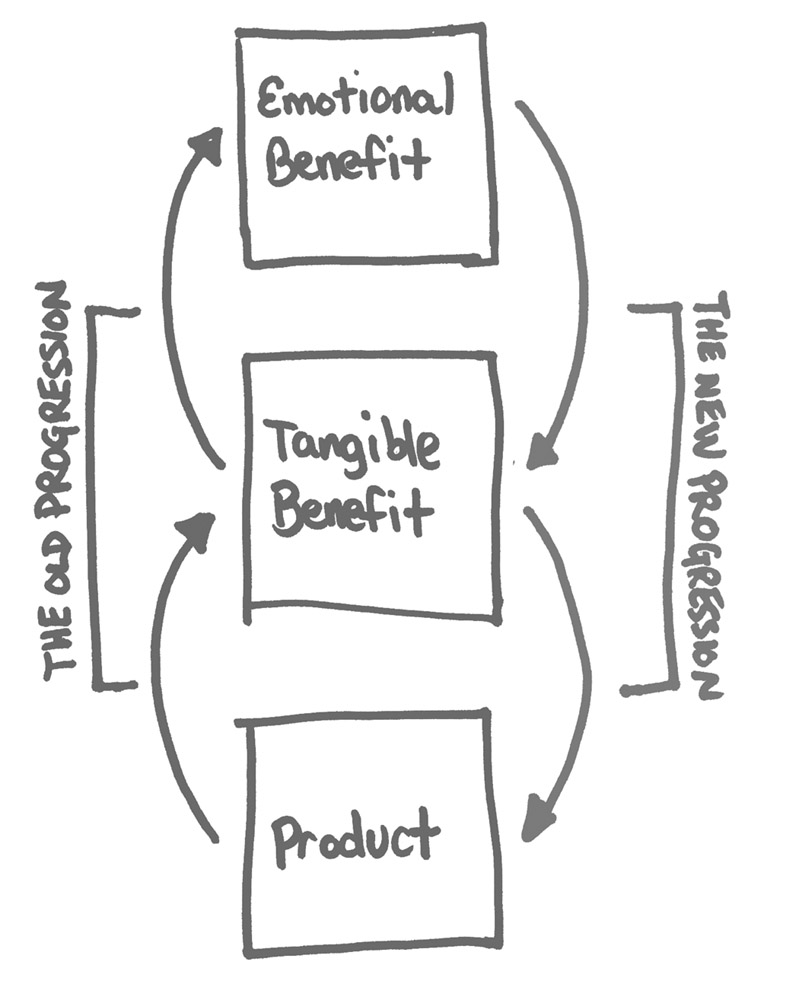

A 'benefit ladder' is a diagram of the ordinary innovation process, beginning with the new formulation that R&D came up with and connecting it with the benefit to consumers. Benefit ladders were considered to be innovative 20-odd years ago, but they have led us to a point where we're grasping at straws to give brands an impact.

If you've never seen one, a benefit ladder is a diagram with three boxes, with arrows leading up from the bottom to the top. The idea is that you begin with the product in the bottom box, move up to the immediate, tangible benefit in the next box ('tastes great' or 'more absorbent' or 'less mess'), and then move up to a broader emotional benefit in the top box. Unfortunately, the top box always seemed to be 'be a better mom,' 'achieve world peace,' or 'have better (or more) sex.'

Well, so far, I've managed to keep my kids in one piece as I've raised them, and which brand of paper towels I used doesn't seem to have mattered. The rungs at the top of the benefit ladder don't seem to be connected to the others, at least when you're climbing up from below. Getting to the top rung is a real stretch.

I have advised people to think about climbing downward on this ladder. In the top box, put a consumer conflict that needs resolution: 'I want to have a clean house, but cleaning is a pain in the neck, it's messy, and it's no fun.' Then think about what is going to resolve this tension - what tangible attributes can a product have that address this conflict in more than one direction, in a fresh way? Then you move to the bottom box, and voilà, you have an iRobot Roomba or Dyson vacuum cleaner.

'Of Course!'

Products that identify a conflict, resolve it, and thus release potential energy successfully often have a feel of inevitability about them; they are ideas that make you think, 'Of course!' It's not until the answer appears that the question seems obvious. Sometimes the product is an advance in technology, like the mobile phone. Other times, it's merely a new combination of existing technology.

'Swiping your credit card right at the gas pump? Why didn't someone think of this before?'

Of course, being ahead of the curve technologically is no guarantee of success. MySpace shone brightly in the social media constellation briefly before being outclassed by the now ubiquitous Facebook. It's all about striking the societal psyche at the right moment.

In the not-too-distant past, the idea that people would pay significant money for "designer" water seemed absurd; enter the fitness boom and toxicity concerns about municipal water. Before the ascendancy of Starbucks, a four-dollar cup of coffee was a ridiculous notion. Digital malware is prevalent all around us yet many are comfortable paying for products and services by proximity with their mobile phones, go figure.

Exercise

Finding The Inspiration

Identify the resolved conflict in the following 'of course!' offerings. Then go to the online or to the mall and find at least 10 products or stores that give you a similar feeling.

Netflix

Tesla

Whole Foods

Uber / Lyft

Venmo

Airbnb

Lululemon yoga clothing

Bird / Lime e-scooters

Amazon.com

Apple iPhone

Just Add Water

When you've climbed down the ladder from consumer conflict to tangible benefit, the goal is to clearly make the connection between the product and the emotional conflict it resolves. Think about Kraft's Easy Mac. This kid-targeted version of good old macaroni and cheese wasn't sold on its 'just add water' premise. The commercials showed kids at home in the afternoon, making a snack for themselves and bickering as siblings do. Mom wasn't around - most likely, she was at work. This wasn't a fantasy vision of a perfect family; it was closer to a picture of how Mom hopes her kids are getting along before she gets home (able to work a microwave and get a decent snack). We weren't hit over the head with it . . . it wasn't even stated at all. The dialogue of the commercial was the smart-alecky younger sister bothering her brother as he made the Easy Mac. But it was a picture of life that was instantly understood by millions of women (and men): I want my kids to have something decent to eat, but I can't be there to make it for them.

Identifying Paradox

To get you attuned to looking for kinetic conflict and sources of potential energy, let's consider a couple of examples.

If our target consumers are women entering midlife, the conflict might be:

Just as my inner self is becoming visible, my outer self renders me invisible.

As a woman is leaving the intensive years of child rearing and is finally done with dirty diapers and trips to the baseball field, she is coming into herself. Perhaps she is getting to pursue her own interests - writing her own poetry, becoming a Pilates instructor, spending more time on herself in any number of ways. At the same time, when she walks down a street, where she used to garner a fair amount of attention (if only from appreciative construction workers), she now passes unnoticed. When she goes into a clothing store, the saleswomen flock to her teenage daughter and ignore her completely.

In our approach, the first step is to create boards filled with images that bring each side of the conflict to life. (See Chapter 5.) Then we gather things from different categories that resolve that paradox. In this case, it might be pictures of Beyoncé, Katy Perry, thong underwear, and a self-published volume of poetry. Our work is to translate their features into our client's category.

Stand back and look at elements that might cross over to whatever you're trying to develop, whether it be a hair-care product or a fast-food dinner. What could you adopt? What's inspiring? What's grist for the mill?

Let's consider another consumer group: 10- to 12-year-old boys. I know this group well, as I live with one of these delightful creatures. A conflict for this group might be:

Treat me like a grown-up, but tuck me in at night.

My son wants to be grown up. He has his own mobile phone but if a text or call comes after ten, which is his bedtime, the parental rule I've imposed is that he should not respond until the next day. I expect him to respect that rule.

He goes to Starbucks, but he orders hot chocolate (or sometimes coffee with five sugars and a gallon of milk).

While outgrowing it, he still has his teddy bear, but Mr. Bear has a special bed in the closet.

He's slowly making the transition from one stage to the next, wanting the grown-up things but not wanting to let go of the boy things yet.

In addition, he's going through all the bodily changes that boys his age go through, so add an extra level of anxiety on top of everything else. He and his peers deal with the tension by making fun of it.

So, what things resolve these conflicts? Gap Kids and Abercrombie (the younger version of Abercrombie & Fitch) provide smaller-size versions of hip grown-up clothes. Computer games touch on this tension as well - it's still playing games, but with high-level technology.

But what about the bodily changes aspect of the situation? Again, think back to my son staring at the hundreds of choices of deodorant on the shelf. If we were developing a deodorant for this age group, we'd look at the perpendicular arrows of 'I want to have what the adults have, but made for me' and 'I'm grossed out by what's happening to my body, but I can make fun of it.'

At the point where those arrows collide and the potential energy lies, you'd be likely to find something like Axe (a hip vibe in deodorants) or Burt's Bees (au naturale appeal), with a Sweatology game that you could download from the Web and play.

Adapt To The Consumer

Whether you're looking at women in midlife, boys in adolescence, or anyone else, the thing to remember about potential energy is that it lies within conflicts of consumer desire: The product adapts to the consumer, not the other way around. To truly understand the paradoxes that pull at someone, it's necessary to step further into that person's world, to make the Copernican Shift.