Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 1: The Ecosystem that We Sell in

Overview

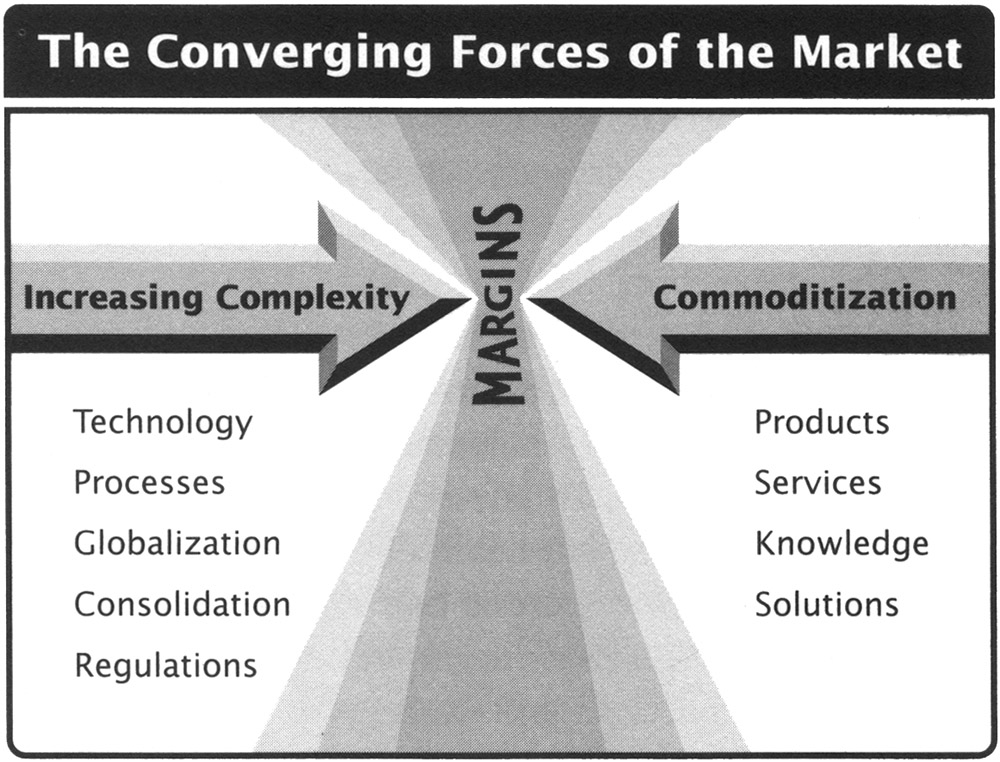

Converging Forces of Rapid Commoditization and Increasing Complexity

Survival in today's sophisticated marketplace requires us to overcome two opposing forces: (1) increasing complexity and (2) rapid commoditization, the pressure from buyers to devalue the differences between goods and services and reduce their decision to the lowest common denominator - the selling price (see Figure 1.1). Let's be direct: The world in which we sell is being pulled apart by these two opposing forces. Even our most enterprise solutions are at the mercy of commoditization as our customers, swimming in a haze of confusion and performance pressure, grapple with tough decisions impacting their responsibilities. The net effect is a deadly spiral of shrinking profit margins.

Seeking competitive differentiation through increasing uniqueness and complexity is a deadly double-edged sword. These competitive advantages rapidly erode as they surpass the customers' level of comprehension. As this occurs, the overwhelming tendency of the customer is to treat all solutions the same - as a commodity.

With a true commodity, price and total transaction cost are the driving forces in the marketplace. As commoditization occurs, sales skills become less and less effective and transactional efficiency becomes the critical edge. The professional salesforce itself soon becomes a luxury that is too expensive to maintain. If your company has chosen to embrace commoditization as a dedicated strategy, it is - or soon will be - pursuing the lowest transactional cost it can achieve, and a book on sales process and skills will not be of much value.

When there is increasing complexity, sophistication, innovation, and value realized are the driving forces in the marketplace. To survive, a company is required to recruit and equip sales professionals who are capable of understanding the diverse situations their customers face, configuring the enterprise solutions offered by their companies, and managing the multifaceted relationships that are required to bring them both together. In short, the ability to create value for customers and capture value for companies is the key. Thus, the good news is that the future of the sales profession is secure in the multidimensional environment. The bad news is that as your company brings increasingly sophisticated offerings to the marketplace, your customers are being left confused. They are less and less able to understand the situations they face and evaluate these enterprise solutions, which tends to limit their decision-making criteria to the simplest elements of your offering, the lowest common denominators - price and specifications. If complexity accurately characterizes your selling environment, this resource is for you.

The impact of the complexity challenge is apparent in a wide range of industries including as examples professional and financial services, software, medical devices and equipment, IT solutions, or manufacturing systems. The people who serve these industries sell enterprise solutions with individual values that range from tens of thousands of dollars to tens of millions of dollars. Sales professionals serving these sectors are highly educated, very sophisticated, and definitely street-smart. And they are well paid. They are levels above the stereotypic image of salespeople that is imprinted on the public imagination.

Even though these professionals are masters of their crafts, a common lament is their frustration at a not unusual outcome of their efforts; one we will label the Dry Run. The generic version goes like this:

A prospective customer contacts your company with a problem that your solutions are expressly designed to address. A salesperson or team is assigned the account. The customer is qualified, appointments are set, and your sales team interviews the customer's team to determine what they want, what their requirements are, and what they plan to invest. A well-crafted, multimedia presentation is created, a complete solution within the customer's budget is proposed, and all the customer's likely questions are answered. Everyone on the customer's side of the table smiles and nods at the conclusion of the formal proposal. Everything makes good business sense. Your solution fills the customer's needs. You believe the sale is "in the bag," but the decision to move forward never comes. The result after weeks, months, and, sometimes, years of work: no sale. The customer doesn't buy from your company and often doesn't buy from your competitors. The worst-case scenario ends in what we refer to as unpaid consulting. The customer takes your solution design, shops it down the street, and does the work themselves or buys from a competitor. Many times, the customer simply doesn't take action on a solution that it needs and can afford. This, with a twist here and there, is the Dry Run. Sure, it's great practice and it's great experience, but this isn't a training exercise. This is the real world of selling, and, in this world, it's your job to bring in the business.

What's going on in this story? The sales team is doing everything it has been taught, but the result is not what is expected. In the diverse environment, the outcome of the conventional sales process is increasingly random and unpredictable. Some of the reasons behind this dilemma have been hinted at but to truly understand the situation, we examine the nature of the enterprise sale itself.

The Mother of All Procurements

Enterprise sales are primarily business-to-business and business-to-government transactions. They involve multiple people, with multiple perspectives, often multiple companies, and frequently cross multiple cultural and country borders. The enterprise sales cycle can run from days to years. Undertaking this level of sale requires significant investment in time and resources.

The $200 billion defense contract that Lockheed Martin won in 2001 may well be the largest enterprise sale in history. Granted, few companies will ever compete for a sale of this magnitude. However, even though this is an extreme example of a enterprise sale, it does share common characteristics with all enterprise sales.

This contract grew out of the U.S. Defense Department's Joint Strike Fighter program, which was conceived in the early 1990s. The Pentagon decided to replace the aging fighter fleets in all branches of the nation's military with a next-generation jet that could be built on a standardized product platform and that combined the features of a stealth aircraft with state-of-the-art supersonic capabilities. In 1995, the United Kingdom jumped into the project when it decided that the fighters in the Royal Air Force and Navy also needed replacing and that this program would be the most economical way to accomplish that task. Today, at least six other countries, including the Netherlands, Italy, Denmark, Norway, Canada, and Turkey, are considering participation.

The contract to design and manufacture jets for this program was so large that it caused a fundamental reconfiguration in the aerospace industry. In fact, the winner of the contract would become the nation's only fighter jet manufacturer. Lockheed aeronautics executive James "Micky" Blackwell called it "the mother of all procurements" and suggested that the Joint Strike Fighter program would eventually be worth $1 trillion to whichever company won it. [1] In 1996, when the Pentagon announced that Lockheed Martin and Boeing had each won a $660 million prototype development contract and would be the only companies allowed to compete for the program's final contract, one competitor, McDonnell Douglas Corporation, sold itself to Boeing. Northrop Grumman, another spurned competitor, tried to merge with Lockheed Martin; after the government blocked that deal, Northrop Grumman declared it would no longer compete as a prime_contractor in the military aerospace market and joined the Lockheed team as a partner.

In October 2001, the final contract, the largest single defense deal ever, was awarded to Lockheed. It called for the eventual delivery of more than 3,000 aircraft to the U.S. military alone, and the Congressional Budget Office valued it at $219 billion over 25 years. That seems to be the tip of the iceberg: The company will easily export another 3,000 planes, and the life of the contract could extend into the middle of this century. Revenue generated by this sale may not hit the trillion-dollar mark that Micky Blackwell targeted, but based on sales of past generations of fighter jets, industry analysts think that it could easily reach three-quarters of that figure.

We've already mentioned the first two characteristics that all enterprise sales share with this contract. Enterprise sales involve large financial investments and long sales cycles. Case in point: the Joint Strike Fighter's several hundred billion dollar price tag and the years that it took to award the final contract.

Another common characteristic of the enterprise sale is that it requires multiple decisions at multiple levels in the customer's organization. It frequently involves multiple organizations working with the customer. In the purchase of many products and services, the buying decision is clear and entails little risk. The customer clearly understands the problem, clearly understands the solution, and can easily sort through the pros and cons of each alternative. There really is not much that can go wrong that would not be anticipated.

In the enterprise sale, there is no single buying decision or single decision maker. The buying process is actually a long chain of interrelated decisions, impacting multiple departments and multiple disciplines that can ripple throughout a customer's organization. In the Joint Strike Fighter program, this chain of decisions stretched beyond the horizon. It included a huge number of decisions with serious implications for the future, such as the decision to pursue a single platform fighter that can be modified for vastly different uses and the decision to award the entire contract to a single prime_contractor.

The difficulty of coping with the long decision chain is compounded by another common characteristic of the enterprise sale: multiple decision makers. Shelves of books are devoted to helping salespeople find and close the decision maker, that one person who can make the decision to buy on the spot. In the case of a commodity sale, there often is just such a person - a purchasing agent or a department head with a budget or senior executive who can simply sign a deal.

In the enterprise sale, however, the search for this mythical buyer is fruitless. There is no single decision maker; often, even the CEO cannot make a unilateral decision and must defer to the board of directors. Certainly, there is always a person who can say yes when everyone else says no, and, conversely, there is always someone who can say no when everyone else says yes. Today, the majority of decisions, quality decisions, are the result of a consensus-building effort - an effort that the best of sales professionals orchestrates. Therefore, the enterprise sale has multiple decision makers, each seeing the issues of the transaction from his or her own perspective and each operating in the context of his or her job responsibilities and their own self-interest. The decision makers in a enterprise sale may be spread throughout an organization and represent different functions and frequently will have conflicting objectives. They can be spread throughout the world, as in the case of a multinational corporation, buying products and services that will be used throughout its organization. They may also represent multiple organizations, as in this mammoth contract, where the different sectors of the military, the executive branch, and the Congress were all involved in the sale, as well as the governments and military forces of other nations.

The enterprise sale, however, is not a run-of-the-mill transaction. The customer's situation is often a rarely encountered or a unique occurrence. The advent of e-commerce brought about just such a situation. Suddenly, an entirely new distribution channel became available to corporations, institutions, and governments. Many organizations floundered as they tried in vain to understand this new world. Should they go online or not? What would happen if they did? What would happen if they didn't?

Organizations that did make a decision to expand online were faced with a second set of critical decisions. The solutions themselves were based on newly developed technology, and customers had few guidelines for judging between them. The results, as anyone who watched the rise and subsequent fall of the e-commerce revolution knows, were widely varied. But one thing is certain: For each successful online expansion, there were hundreds of equally spectacular failures.

If you examine the Joint Strike Fighter program, you find that the Pentagon invested years in exploring and defining the problems of its existing fighter fleets. It determined the two companies most likely to create the best solutions to those problems and paid them $1.32 billion to develop prototypes. Only then did they make a final decision.

A final characteristic of the enterprise sale and major consideration for sales success is that customers require outside assistance or outside expertise to guide them through complicated decisions. They cannot do this by themselves. You should begin to consider this question: To what degree do you and your team provide this expertise? To help organize your thoughts, consider that your customers need this expertise in one or more of three major areas.

First, they may require outside expertise to help Diagnose the situation. They may not have the ability to define the problem they are experiencing or the opportunity they are missing. In many cases, they may not even recognize there is a problem. So consider: To what degree do you and your team assist the customer in completing a more thorough Diagnosis'?

Second, even if your customers could accurately diagnose their situations, they may not be able to Design the optimal solution. They may not know what options exist, how they would interact, how they might integrate into their current systems, and other such considerations. To what extent do you and your team enable customers to design comprehensive solutions?

Finally, even if your customers could Diagnose their problems completely and Design optimal solutions, they may not have the ability to implement the solutions and Deliver the expected results to their organizations. To what degree do you and your team provide implementation support to assure that the maximum impact of your solutions is achieved?

In summary, the characteristics of enterprise sales involve long sales cycles. They require multiple decisions that are made by multiple people at multiple levels of power and influence, each of whom approaches the transaction from his or her own perspective. Finally, they involve complicated situations and sophisticated and expensive solutions that are difficult for the customer to understand, evaluate, and implement.

In addition to the elements of the enterprise sale itself, the two environmental forces that we introduced at the beginning of this chapter - commoditization and increasing complexity - also have a direct effect on sales success. To round out the portrait of the world in which we sell, we take a closer look at each.

[1]Brendan Mathews, "Plane Crazy: The Joint Strike Fighter Story," Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (May/June 1998).

Driving Forces of Commoditization

Commoditization is a big word for a phenomenon that salespeople face every day, that is, the pressure from the customer to devalue the differences between their goods and services and reduce their decision to the lowest common denominator - the selling price. The pressure to treat all entries in a category of products and services as identical is driven, in some instances, by very real forces and, in others, by emotional needs. In either case, the pressure exists and sales professionals must deal with it.

Technology is one of the real forces driving commoditization. A good example of how emerging technology can commoditize a product is the personal computer and development of electronic commerce. Before the Internet, enterprise-level personal computer (PC) sales were considered enterprise sales and all the major computer manufacturers had large sales organizations dedicated to that task. Today, a large portion of those sales positions have been eliminated. PC makers still maintain salesforces for their high-volume customers, but buying a number of PCs for a company can also be accomplished in a self-service, commodity-based transaction.

Even a short visit to a Web site such as Dell.com makes the point abundantly clear. Dell Computer Corporation has played a leading role in the commoditization of the PC and has profited handsomely from its work. The company was founded on a direct-to-the-customer model that eliminated the external sales and distribution chains that other PC manufacturers depended on. When e-commerce technology appeared, Dell was the first to move online. Starting in 1996, Dell customers who wanted a self-serve transaction could research, configure, and price their PCs, associated hardware, and off-the-shelf software on the company's Web site. Today, they can do the same at two or three of Dell's major competitors. They can compare prices and make their purchases without ever speaking to a salesperson. What was once solely considered a sophisticated product (and sale) has been transformed by experience, knowledge, and technology into a product (and sale) that can just as easily be treated as a commodity.

Dell has successfully created the best of all worlds. For the customers who can determine their own needs, configure the computer they want, and set up and use the computer without assistance, Dell has provided the lowest cost of manufacturing in the industry and has enabled its customer to order a computer with little or no sales support. On the other end of the spectrum, for the customer looking to set up an elaborate network of PCs or for a complicated e-commerce business, Dell has assembled a team that can provide high-level support in Diagnosing, Designing, and Delivering sophisticated solutions.

The second real force driving commoditization is the lack of differentiation between competing products in the marketplace. The growing similarity between the products and services that compete in specific market niches is not a figment of our imaginations.

To return for a moment to the personal computer, corporate buyers often see little difference between one company's PCs and the products of its major competitors. Who can blame them? Perhaps the shape and color of the computer is different; so is the name on the box. But, the main components of the computer - the processors, memory, disk drives, and motherboards - are often identical. Therefore, many buyers make this purchase decision based on price.

The similarity between competing products and services is a function of industry response times. Unless they are protected by law (as in the case of new prescription drugs), the length of time that the inventors of new products and services enjoy the advantage of being first into the market is getting shorter and shorter. Competitors see a successful or improved product and quickly match it. Therefore, one important reason for the increasing difficulty in differentiating products and services is that, in actuality, they are increasingly similar.

Another reason it is getting tougher to differentiate products and services is that customers don't want to differentiate them. The more complicated products and services are, the more difficult it is for customers to compare and evaluate them. Analyzing and deciding between long lists of nonidentical features is hard. Simply comparing the purchase prices is much easier. Customers, by the way, are the third driving force of commoditization.

Customers are always trying to level the playing field. They attempt to reduce enterprise sales to their lowest common denominators for good reasons. The most obvious is financial. When customers are able to convince vendors that their offerings are essentially the same, they exert tremendous downward pressure on the price. For instance, if General Electric's jet engines are the same price as Rolls Royce's jet engines and the customer can't or won't see any difference between the two, what must those vendors do to win the sale? Unfortunately, the easiest answer, and the one that takes the least skill to execute, is to cut the price, which is why so much margin erosion occurs at the point of sale.

An example of the extreme impact this can have on a business involves a client who came to us after their business had taken a devastating hit. This company had developed a manufacturing technology that became a standard in the chip manufacturing industry. They produced a piece of capital equipment, sold about 300 units per year, and enjoyed a very large market share. The situation was too good to be true, and a competitor entered the marketplace offering the "same thing" for 32 percent less. The original manufacturer did not initiate the diagnostic process we describe and, faced with the threat of losing customers, lowered prices in response. Their average selling price dropped by 30 percent during the following year, resulting in a reduction of $24 million in margins. The irony of the story is the upstart competitor, who made the claims, sold only 15 units, a 5 percent market share. The manufacturer's inability to respond in a more productive manner nearly destroyed their business.

Customers also try to oversimplify transactions with higher complexity for emotional reasons. Often they are in denial about the extent of their problems. Think in personal terms: If your stomach burns and you chew an off-the-shelf antacid, your problem must be temporary and is easily solved. If you go to your doctor, who discovers you have an ulcer, your problem jumps to an entirely different level.

Fear drives customers to oversimplify transactions. Our customers are professionals, and it is difficult for professionals to admit that they don't understand problems and/or solutions. We need to take into account that our customers may be concerned about appearing less than competent in front of us and in front of their bosses. So, instead of asking questions when they don't understand something, they may simply nod and reduce the transaction to what they do understand - the purchase price.

Finally, there is the emotional issue of control. We regret the negative stereotype of a professional salesperson that exists in many customers' minds. Customers are fearful that by acknowledging complexity and admitting their own lack of understanding, they lose control of the transaction and open themselves to manipulative sales techniques. The simpler the customers can make a sale, the less they must depend on salespeople to help them. This is their way to maintain control of the transaction and protect themselves from unprofessional sales tactics.

Driving Forces of Complexity

The portrait of the world in which we sell is almost complete. We have examined the nature of the enterprise sale and the environmental pressures that are forcing them into commodity-like transactions. The last element in the picture is an equal and opposing pressure that, in essence, is forcing additional complexity into already-complicated transactions. Simply put, environmental forces are adding more complexity to the mix. We are seeing complexity piled on complexity.

Many of the driving forces of complexity are emerging from the changing nature of business itself. The structure of our organizations is becoming more complex. In many cases, decentralized organizational structures have replaced the fixed, hierarchical infrastructures on which traditional companies were built. In other cases, consolidations are having the opposite effect and have taken decisions away from the technical, clinical, and operational levels to professional managers who frequently take a vital but limited financial view to their decisions. In addition, the speed with which these transformations are occurring is unprecedented. The result is increasing difficulty in understanding and navigating our way through a customer's business. Identifying the powers of decision and influence in today's corporate labyrinths isn't easy either. With increasing frequency, the customers themselves cannot define their decision process.

The trend toward globalization is exacerbating the growing complexity of organizational structure. We are often selling into decentralized companies that span the globe and encompass dozens of different languages and cultures. "Where in the world are the decision makers?" is not a rhetorical question in an increasing number of situations.

The restructuring of organizations has extended back down the supply chain. Customers are consolidating, fewer companies are controlling higher percentages of demand, and fewer competitors are controlling higher percentages of supply. It's an environment where the winner takes a substantial share, if not all, of the marketplace.

At the same time that our customers are demanding commodity-based pricing from us, they are demanding more multifaceted relationships with us. They are drastically reducing their supply bases and asking the remaining vendors to take a more active role in their business process. They want those of us who are left to become business partners and open our organizations to them. They are also asking us to add value at much deeper levels than we have traditionally delivered to their organizations.

The customers' desire to build tighter bonds with fewer vendors is adding complexity to the sales process. Buying decisions include more considerations and more players, and those players are often located at higher levels in the organization. This is on top of the multiple decisions and multiple decision makers that already characterize sophisticated transactions.

There is an even more sobering consideration here: If your customers are tightening up their supply chain, there will be fewer opportunities in the long run. One lost sale in this environment could easily translate to the long-term loss of the customer. We saw an extreme example of what that can mean in the case of the Pentagon's contract for the Joint Strike Fighter. The companies that did not win that sale had to either abandon that business or accept supporting roles working for the winner. How many customers can you afford to lose on a long-term basis?

Increasing levels of complexity can also be found in the situations and problems our customers face and in the solutions that we offer them. We tend not to see the world through our customers' eyes, but when we do, we find that they face many problems. Their business environments are more competitive than ever, technological advances are radically altering their industries and markets, and their margins for error are always shrinking. The increased complexity of the environment translates directly to increased complexity in their problems.

The solutions that we design to address those problems are correspondingly complex. Products and services must be designed to transcend geographical borders and connect and integrate decentralized structures. Our solutions need to incorporate diverse technical innovations and address the needs created by technological change. In addition, our margins for error are always shrinking. The enterprise solution and the situation it is designed to address are ever changing and increasingly sophisticated.

Finally, complexity is driven by competition. To stay on top of our markets, we often find ourselves trapped in "innovation races" with our competitors; in doing so, we can actually outrun the needs of our customers. Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen calls this performance oversupply and describes the phenomenon in his book, The Innovator's Dilemma: "In their efforts to stay ahead by developing competitively superior products, many companies don't realize the speed at which they are moving up-market, over-satisfying the needs of their original customers as they race the competition toward higher-performance, higher-margin markets." [2]

Ironically, when the complexity that we add to our products and services exceeds the needs of our customers, they respond by ignoring the features they do not need and by treating our offerings as if they were commodities. Here's how Christensen traces the process: "When the performance of two or more competing products has improved beyond what the market demands, customers can no longer base their choice on which is the higher performing product. The basis of product choice often evolves from functionality to reliability, then to convenience, and, ultimately, to price." Here is yet another example of technological innovation driving commoditization.

There are two points to all of this: First, if you are already involved in enterprise sales, you can expect them to get more complex. Second, if you are not selling a simple commodity but have a relatively simple sale at this time, you may well end up with a full-blown enterprise sale in the near future.

[2]Clayton M. Christensen, The Innovator's Dilemma (Harvard Business School Press), p. xxiii.

Getting Back to the Dry Run

Now that we have a complete picture of the world in which we sell, we can turn back to the Dry Run. In every variation of that scenario, sales professionals are doing everything they have been taught, they are offering high quality, cost-effective solutions, and yet their conversion rate of proposals to sales is in free fall. Why?

The answer is that the nature of the enterprise sale and the opposing environmental forces of commoditization and complexity are making it extraordinarily difficult not just for sales professionals to bring in revenues, but for customers to fully understand the problems and opportunities that they face. The enterprise sale and the forces that affect it are impairing our customers' ability to make rational purchasing decisions. Ultimately, that is why the salespeople in the Dry Run did not win the sale. Their customers were unable to make a high-quality decision.

We are not saying the customers are incompetent, although many frustrated salespeople level that charge. The vast majority of customers are fully capable of understanding sophisticated transactions. The problem is they don't have a process that can help them interconnect the key elements of their business to bring the required perspectives together to enable them to make sense of these transactions. That is the underlying thesis of this resource and the key insight that allows us to get inside the enterprise sale: Customers do not have the depth of experience and knowledge in each of numerous diverse subjects that allows them to form high-quality decision-making processes, which are specific to the requirements of each and every purchase of goods and services. In multidimensional decisions, one size does not fit all.

The often ignored reality of the enterprise sales environment is that our customers need help. They need help understanding the problems that they face. They need help designing the optimal solutions to those problems, and they need help implementing those solutions. The next logical question is: What can we, as sales professionals, do about it? The obvious answer is to provide the help our customers need. But, unfortunately, that isn't the strategy taken by the majority of the leaders of sales organizations.

By and large, traditional sales leaders are focused on sales numbers, not the reasons behind them. They understand numbers very well and, like everybody else, they know that selling is a numbers game. So, the answer that we usually hear can be summarized in two words: Sell harder. They try to solve the problem by pumping up the system. They command their troops to make more cold calls, set more appointments, give more presentations, overcome more objections, and, thus, close more sales. If the company's conversion rate on proposals is 10 percent, they will simply write and present more proposals.

We've already described one problem with the "sell harder" solution. In today's environment, the number of potential sales is not infinite. At some point, you run out of viable opportunities and are forced to start chasing more and more marginal prospects. The other, more fundamental problem with "selling harder" to win the enterprise sale is that it fits the popular definition of insanity: You are doing the same thing repeatedly and expecting a different result. In the next chapter, we show you why that is so.