Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 2

What Is Influence, and Why Do We Want to Have It?

Influence and Power

The word "power" is a noun that indicates ability, strength, and authority. "Influence" is most often used as a verb, meaning to sway or induce another to take action. (It can also be used as a noun, often interchangeably with power.) In this book, we will consider power to be something you have and influence to be something you do. Electric power exists only as a potential source of light in your home or office until you flip a switch (or activate a beam that does the switching). Likewise, your power exists only as potential until you activate the sources through the use of influence.

Many sources of power are available to you. Among them are

- Formal authority associated with your role, job, or office

- Referred or delegated power from a person or a group that you represent

- Information, skill, or expertise

- Reputation for achievements and ability to get things done

- Relationships and mutual obligations

- Moral authority, based on the respect and admiration of others for the way that you act on your principles

- Personal power, based on self-confidence and commitment to an idea

Power may be used directly (for example, "You are going to bed now because I am your mother and I say so") or indirectly, through others (for example, "Let Jack know in a subtle way that I would prefer the other vendor"). If the demanding party's power is understood, and considered legitimate and sufficient from the point of view of the responding party, the action will happen. In general, when power is called for, it is better to use it directly to avoid confusion, delay, or doubt. Power used indirectly can sometimes be experienced as manipulation. Many situations call for the direct use of power. Emergencies and other situations in which rapid decision making is essential are times when fast and effective action is more important than involvement and commitment.

In day-to-day life, the direct use of power has several limitations.

- Others must perceive your power as legitimate, sufficient, and appropriate to the situation.

- The use of power seldom changes minds or hearts; thus you cannot count on follow-up that you are not there to supervise.

- The direct use of power does not invite others to take a share of the responsibility for the outcome. Others do not have the opportunity to grow by having to make decisions and live with the consequences.

Influence behavior uses your sources of power to move another person toward making a choice or commitment that supports a goal you wish to achieve. Various sources of power will be appropriate with different people and in different situations. They will support the use of a variety of influence skills. Using influence rather than direct power sends a message of respect to the other. It results in action by the other that is voluntary rather than coerced; quality and timelines are likely to be better. It is also the realistic choice to make in the many situations we encounter in which we need to get things done through other people over whom we have no legitimate power.

Influence and Leadership

Leaders must be able to use both approaches - direct power and influence skills - and must know when each is appropriate. Few leaders are satisfied with blind obedience (obedience in adults is never "blind" - it is an emergency response, a fear response, or betrays a lack of interest in and responsibility for the outcome). Most leaders want to work with people who are willing to influence as well as to be influenced.

Because influence tends to be reciprocal, part of a relationship, it is important for a leader to let others know when and how he or she can be influenced on an issue. A big mistake often made by leaders and managers is to act as if they can be influenced (for example, by asking people what they think about something) and then communicating (often by arguing with their suggestions) that the decision has already been made. Presumably, the leader was hoping that people would come to the same - obvious to the leader - conclusion, so that they would be committed to the decision. This only creates cynicism and has given "participatory management" and "employee empowerment" bad names. If you have to use direct power, use it with confidence, not apologetically. Then involve people about something related to the issue, where you can be influenced. For example, suppose that a reorganization will occur whether your direct reports want it to happen or not. Although you might be tempted to try to develop support for the action by seeming to engage others in the decision, you know that would be inappropriate given the fact that the decision has already been made. Announce it and give people time to absorb the news, express concerns, and ask questions. Then ask, "What support will you need from me to communicate about this and plan transitions for your employees?"

Successful leaders learn and practice a wide variety of influence behaviors. They keep the goal in front of them and act in a way that is consistent with the aim of achieving that result, through and with others. Leadership in a team, family, or community organization is usually shared. The option to use direct power is often less available or effective, yet the responsibilities remain. Those in both formal and informal leadership roles must call on their personal influence skills to align other members toward a shared goal and to energize and inspire them to do what it takes to achieve it.

Your Sphere of Influence

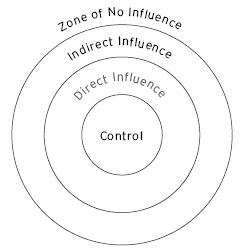

Each of us has a "sphere of influence." This includes issues and areas over which we exercise control, those where we can directly influence the outcome, and those where we can influence the situation indirectly through other people or as part of a group.

Use Figure 2.1 to chart your current sphere of influence. In which aspects of your life can you control an outcome by yourself?

Figure 2.1. Sphere of Influence

What issues in your life are open to influence that you can exercise directly? Where do you have the opportunity to influence a situation indirectly by getting another person or a group to do the direct influence? What are the areas and issues in your life that are important to you, but where you see no opportunity to influence?

As you review your chart, notice how active a role you are taking in influencing the outcome of issues and events that you care about. Is there anything about which you care deeply that you perceive as being outside of your sphere of influence entirely? Many people find that their areas of direct control are limited to choices about their own behavior, but that it is possible to influence, either directly or indirectly, many events and outcomes in which they hold a strong interest.

Typical examples for sphere of control might include:

- What to wear (what is "business casual," anyway?)

- The order in which you do certain things

- The level of your own commitment

- Your own behavioral choices, for example, how to communicate with or influence someone

- How to organize your workspace or closet

These are choices you can make on your own - no one else needs to be involved or consulted (although you may opt to involve or consult others).

Your sphere of direct influence may include issues involving:

- Family members

- Friends

- Manager

- Team members

- Peers

- Direct reports

- Internal and external customers

- Neighbors

- Vendors

- Neighborhood business owners

- Local government officials

- Local media

- Members and leaders of professional and community organizations of which you are a member

In these cases, you can go directly to the person or group you wish to influence and use your skills to achieve the results that are of interest to you.

Your sphere of indirect influence may include:

- Senior managers in your company

- Other department heads

- Regional and national government officials who represent you in some way

- Competitors

- The leadership of large companies with which you do business

- Your customers' customers

- The national media

You may be able to have an impact on them through others who are in a position to influence them directly; through organizing a group to influence together; or through the act of voting, organizing an e-mail or letter-writing campaign, or other means.

Most of us would acknowledge that we have little or no influence in areas such as the global economy, a competitor's business strategy, large-scale trends such as industry consolidation, or decisions made by leaders of countries we don't live in, any more than we do the weather. Yet these and other decisions and events can have an impact on our lives and on how we influence. For example, knowing that a certain industry is having difficulty filling orders because of shortages of a raw material from a country that is at war may affect our approach to negotiating a business deal. We may not have any impact on the route a hurricane will take, but we can use information we have heard about it to influence a relative's travel plans.

Empowerment: Buzzword or Reality?

If asked, most people would say they do not want control over other people - but neither do they want others to have control over them. Research on work-related stress has demonstrated that those with low power and high responsibility have the greatest levels of stress. Our physiological "fight or flight" response is intensified when we feel the pressure to take action but do not have the legitimacy or the resources to make something happen. Organizations in which people feel they have little influence over matters that affect them become "cultures of complaint." For example, I remember two trips I made to the former Soviet Union, about two years apart. During the first trip, just before the ascent of Gorbachev and the liberalization of the totalitarian government, I was struck by the fact that few people tried to talk to us. When they did, they asked questions about life in the United States, but rarely shared information about their own lives. Two years later, it was easy to see that glasnost, or openness, was working; people talked with us constantly about their lives. However, perestroika (restructuring) clearly was not yet a reality. Thus, nearly all the conversations consisted of stories about how bad things were or what terrible things the government had done to them or to their parents. They now knew and could talk about everything - but did not feel that they could do anything about it - so they complained.

While there has been much discussion in organizations and families about empowerment, the reality is that, as individuals and groups, we cannot wait passively for others to give us power. Organizations, institutions, and leaders may offer us power, but we can use it only when we have created and accepted empowerment for ourselves. Accepting empowerment means accepting responsibility for the outcome of our actions. As a buzzword, empowerment has probably run its course - but as a concept, it has a lot of life left. In most organizations and families these days, true empowerment means an openness to influence from and in all directions.

In today's information-based organizations, direct power and control are rare commodities. Particularly in competitive, global organizations, decisions must be made on the basis of complex information drawn from a variety of sources. Governance of the organization is often broad-based. Much of the work of these organizations occurs across functions, outside of formal hierarchies, sometimes by teams of people who rarely, if ever, meet face-to-face. Increasingly, people who are empowered to take action make decisions across boundaries of space, time, and nationality.

Families today are less hierarchical. In North America, Australia, New Zealand, and much of Western and Central Europe, the typical family is a complex unit made up of individuals with a variety of sources of power and levels of responsibility. Typically, family roles are more fluid than in the past. In many families, both parents work; in some of those cases each person may have a career that is very important to him or her. In single-parent families, where the parent is working, children may assume greater responsibilities. Traditional extended families are often less available or geographically convenient, especially in North America. Children may have information and economic power bases that enable them to participate in family decisions on a more equal basis than in the past, when parents and grandparents were keepers of traditions, knowledge, and authority. (Any family that owns a computer knows that the power balance in families has changed.) Peer groups offer an alternative source of need satisfaction for children and adolescents, rendering the nuclear family less powerful, whether we like it or not.

In communities, also, the traditional power relationships in Western society have broken down. There is no overarching institution, like the church in medieval society or Tammany Hall in turn-of-the-20th-Century New York, to provide the final word on what can and should be done. Instead, there are multiple competing interest groups, each with its own set of problems and preferred solutions. It sometimes seems that the community is divided into tiny fractions, each with a particular vested interest around which to organize. Yet, people from many cultural, religious, occupational, economic, and educational backgrounds must be able to come to agreement on solutions to problems that affect all of them.

In today's more open and empowered organizations and societies, opportunities for exerting influence and power abound for those who are willing to accept the attendant responsibilities and accountabilities.

Benefits and Costs of Exercising Influence

In this complex, multi-ethnic society, individuals must depend on their interpersonal skills to build coalitions and make things happen with and through the other people within their spheres of influence. The benefits are clear - you can achieve goals that you could not accomplish by yourself and reduce the stress associated with having a lot of responsibility without sufficient resources to do the job. You can create visibility and opportunity for yourself and for ideas, causes, or projects that are important to you.

For example, you may be responsible at work or in your community for a project that does not have its own budget. In order to achieve the results you hope and are expected to accomplish, you will have to beg, borrow, or steal the resources that are required. You will need to influence the right people to take an interest in your project's success and be willing to contribute time, energy, equipment, people, or money to make it happen.

Or perhaps you would like to purchase a vacation home, but you know that it will require some voluntary sacrifices on the part of everyone in the family to make it a reality. You may have to forego regular vacations for a couple of years. You will have to influence the rest of the family to share your vision and trade off near-term pleasures for longer-term satisfaction.

I remember a client who called me in despair one day to report that he was near exhaustion; nobody seemed willing to help him complete a long report that was due the following week, and he did not know how he was going to finish in time. I asked him what he had done to get some support from his teammates. He answered, "They can see that I am over my head and nobody has offered to do a thing." "Yes," I said, "but have you asked them?" He allowed that he had not. The next day, he called back to report that everyone he had asked had been willing to do something. "They thought I didn't need help," he said, wonderingly.

The story above illustrates an obvious benefit. Making the effort to influence can pay off in many ways. At the same time, exercising influence can be costly in time and effort, and sometimes in other, more subtle ways. Once we have become active in influencing a particular outcome, we may create expectations on the part of others that we will continue to champion certain ideas and values. By taking an active role, we may also face more in the way of conflict and feel that we have to accept greater responsibility. It is always useful to balance the costs and benefits when deciding whether it is worth putting forth the energy required to influence.

Where Should We Exercise Influence?

Although some issues at work, at home, and in community activities are appropriately handled through the use of direct power or simple communication, many others lend themselves particularly well to influence. Influence issues are ones that require mutual agreement and commitment.

Typical workplace influence issues include:

- Getting support for ideas

- Assigning responsibilities in a team

- Acquiring needed resources for a project

- Being assigned to interesting projects or career development opportunities

Some family or household issues that lend themselves well to influence include:

- Distributing chores, tasks, and responsibilities

- Planning for vacations or outings

- Assigning proportions of costs for shared activities or household expenses

- Making decisions about major purchases

In community activities, almost everything is subject to influence, since most people are volunteering their time. Examples include:

- Convincing the right people to serve on a committee

- Gaining agreement on principles and processes

- Getting people to deliver on commitments

- Managing disagreements and conflicts

Developing and Improving Influence Fitness

All of us learn early in our lives how to influence the people who are most important to our well-being. As infants, we have only a few means of communicating our needs and wants. Gradually, we develop a complete set of influence muscles. Toddlers experiment with a wide variety of means to exert influence. Through observation, education, experience, and experimentation, we tend to develop a favored set of influence skills - ones that we have been most exposed to or that have worked the best for us. As long as we remain within the context (family, culture, school, workplace) where we have been successful as influencers, there is little need to develop some of the underused or rejected skills. However, when we embark on new experiences, encounter new problems, or meet new people, we may find that our present levels of expertise do not allow us the flexibility we need to be successful.

We view developing influence skills as analogous to developing physical fitness. You have all the muscles you will ever need, but a good fitness program helps you build and develop them so you can be more powerful, graceful, and flexible - in greater control of your own physical and mental well-being. Similarly, you already have all the basic influence muscles you need, but some of them are probably underdeveloped or flabby due to lack of use. A purposeful program for developing influence fitness can also enable you to become more powerful, graceful, and flexible - more effective as a person at work, at home, and in your community.

Reading this resource can introduce you to the concepts involved in conscious and effective influencing, especially if you do so with specific influence opportunities in mind. But only by practicing the behaviors in a safe environment, where you can count on receiving honest feedback, will you truly develop those influence muscles. (See Appendix A for some suggestions about setting up a coaching partnership.)