Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 8: Fault #5: Monotonous Voice and Sloppy Speech

Overview

Speech is a mirror of the soul. As a man speaks so he is.

- Publius Syrus

Your voice is your calling card. Over the phone, it's responsible for the entire impression you make on your listener. Whether you bore or enthrall - a lot depends on how you sound.

People's initial perceptions of each other break down three ways: visually (how we appear), vocally (how we sound), and verbally (what we say). The verbal aspect accounts for only 7 percent of how we are perceived; how we look forms 55 percent of the impression, and how we sound a surprising 38 percent. Yet the sound of our voice is something we give little thought to.

But you have to be conscious of your voice - and of how to change it - throughout your speech. As anyone who has heard a droning speaker knows, the wrong voice, besides making a bad impression, wrecks an otherwise compelling speech. A monotonous tone, mumbling, lack of clarity, and poor enunciation leave the audience noticing your voice and not your words.

A voice is not a neutral thing: It's either a wonderful asset or a serious liability. It either conveys control and confidence or proves a lack of both. But it should be your greatest aid in being interesting and exciting, because it can insert variety into a speech with such ease. To battle an audience's short attention span, speakers need to insert something interesting every three to four minutes. But that doesn't mean coming up with stories and jokes exclusively; you can use your voice to get attention immediately. You can polish your voice just as you polish your speech. All it takes is awareness and practice.

Listen to Yourself - Often

The first step to a powerful voice is getting to know yours. That's not as silly as it sounds. You may think you know your voice; after all, you're always speaking to people at work, at home, and on the phone. But in those instances you're listening to them, not to yourself.

Getting your voice ready for a speech means listening to the way you start sentences, form vowels, and pause after periods. You should practice speaking aloud often. Use your own words, the newspaper, anything. Read to the kids, to the dog; recite in the shower. Develop a love for good speech; listen to audiocassettes of powerful speakers reading book excerpts. Listen to how classically trained actors such as James Earl Jones or Meryl Streep use their voices, as instruments of feeling.

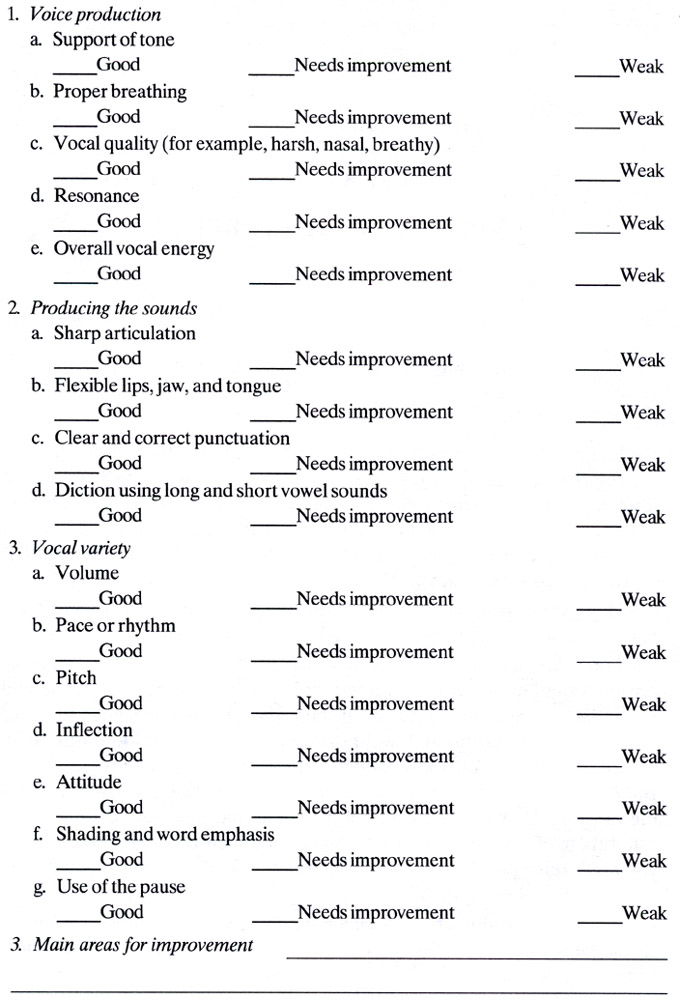

Look in the mirror to see how you are making the sounds. Make a habit of speaking aloud to yourself every day. Use a tape recorder and the exercises in this chapter and listen to your progress. Evaluate yourself often; use the form at the end of this chapter. Once you have started to listen to your voice objectively, you're ready to tackle the fine points of controlling it.

How to Build a More Interesting Voice

Speakers have many tools at their disposal for building vocal variety:

Volume. Volume adds variety to whatever you say.

Practice: Say the word no over and over, starting very softly (almost whispering) and working your way to very loud (almost shouting).

Pitch and Inflection. Different from volume, pitch and inflection reflect your overall tone.

Practice: Say the following, letting your voice follow the words: "Let your voice come down evenly, smoothly as a sigh. Then evenly up and ever so high. Hold our tones level and high today; then level and low tomorrow, I say. Let tones glide high, then slide down low. Learn to say, "no, no, NO." Recite the "do, re, mi" scale, going from a high tone to a low one. Or try the numbers one through eight, going up the scale and coming down again.

Pace and Rhythm. How fast or slow you articulate the words and sounds.

Practice: Read a rhyme such as "The Ballad of Green Broom." Slow down each time you say, "Broom, Green Broom" and the words that rhyme with it. Read the rest very quickly.

Emphasis. This affects your word and syllable stress. The key point is to be sure people get your main ideas. Help them by subverting the less important ones. A common fault of speakers is to emphasize too many things; you should isolate the key points you want to emphasize.

Practice: Use a simple declarative statement such as, "I am going to the store." Use the same sentence to answer a series of questions, emphasizing the appropriate word to answer the question. Subvert the unimportant words.

Many Americans have the bad habit of fading away at the end of a sentence. This can be dangerous in certain situations. Imagine you were given the task of diffusing a bomb, and the person giving you instructions says, "Whatever you do, don't touch the...." That last word could be a lifesaver! Although the last word is not always that dramatically important, it doesn't mean you should just let it drop out of hearing altogether.

Attitude. The same word or phrase can take on radically different meanings, depending on the attitude implicit in your voice.

Practice: Say well as if you were: annoyed, disgusted, surprised, thrilled, in doubt, suspicious, thoughtful, and pugnacious

The Pause. Powerful speakers use the pause several ways - for emphasis, effect, and mood. Pauses can be long, medium, short, or very short (when you're just drawing a breath). They can also signal a transition.

There are four types of pauses:

The Think About it Pause: Gives people a chance to digest what you have said (one to two beats long). It can be effective to pause before you deliver an important point, although it's not good if it's so overused that it becomes boring.

Transitional Pause: Take a short pause between two minor points (one beat) and a longer pause (two to two and a half beats) for transitions between two more important points.

Emphasis Pause: Take a long pause before you make a statement or ask a question where you want people to think about the implications and meaning of what you have just said (two to three beats).

Pregnant Pause: Similar to the thinking pause, but used most often to create effect (two to three beats).

Practice: The next time you have to deliver good news, practice your pause. "Wait until I tell you the good news!" Stop. Count to three slowly. You'll sense the anticipation in your listeners. Enjoy it and feel its power. Then tell them the news.

Practice Your Vocal Variety

Here are seven sentences you can use to practice vocal variety. Say each sentence several times, each time using different pitch, rhythm, and word emphasis.

Why aren't you all lying on the beach in Hawaii right now?

(Try this as if you were angry, then as if you were motivating your team.)

How many of you paid all of your income tax last year?

(How does the sentence change if you emphasize the word "all"?)

What would you do if you knew you only had one month to live?

(Say this in a slow, measured tone. Then repeat it at a faster pace, emphasizing the words "one month." See the difference?)

This occasion will go down in history.

(There are two interpretations to this statement: the "occasion" might be a happy one, or it could be a day of infamy. Convey the two different meanings using pitch, volume, and attitude.)

I'm going to tell you how you can make $25,000 in 25 minutes.

(Pauses can make this sentence quite effective. Where would you put them?)

I was told two years ago I had three months to live.

(Emphasis can bring out the contrast between the words "two years" and "three months.")

Let me tell you how I won the lottery!

(Use all the tools to vary this sentence in as many ways as possible.)

Learn to Loosen up

Facially tense people have more monotonous voices, because they are not using their jaws and not changing their tone enough. An effective voice is relaxed and flexible; the variety so important to a lively speech will only result if you have loosened up your voice ahead of time and speak with an open throat and a loose, active lower jaw. With an open throat, sounds are no longer tight and squeezed.

To open your throat, relax the whole area around it. Rotate your head slowly to one side for a count of eight, and repeat for the other side. Think of clothes dangling on a line - limp and at ease. Then indulge in a nice big yawn. Right before you finish the yawn, lazily recite the vowels "A, E, I, O, U." All your throat exercises should be put together with very open sounds and done very lazily, effortlessly, and slowly.

Now work on getting an active jaw. Americans are known to have tight jaws, which makes for poor diction. Most American men, in fact, have "cultural lockjaw"; they speak like Clint Eastwood, who keeps his mouth almost closed when he speaks. Women tend to have more interesting and varied voices because they are more facially animated. You have to open up your jaw on certain vowel sounds and diphthongs (vowel sounds that come together, like now). Say cow, with your hand on your jaw, and notice the jaw movement.

Practice: Try "How now, brown cow." Make these sounds slowly and easily. Use a mirror to make sure you are really shaping the sounds. The tight jaw style of Gary Cooper and Clint Eastwood may be great for movies, but it's not good for public speakers.

Other Keys to Clear Diction

Our breathing, throats, and jaws all play an important role in how we sound. But clear diction is also governed by our lips, teeth, and tongue. Lips should hit against each other on the "P," "B," "M," "W," and "WH" sounds.

Practice: Create these sounds and the vowels in between by saying "PAPA," "MAMA," and "WAWA." Make sure your lips hit each other and build your speed. Try longer phrases, increasing your speed as you go along: "We have rubber baby buggy bumpers." "Peter Prangle picked pickly prangly pears."

Keep practicing until you have an open throat, an active lower jaw, strong lip muscles, and a flexible tongue that can trip lightly over tongue twisters.

Variety Through Emphasis

One of the biggest faults of American speakers is that we give everything equal emphasis. Read the following paragraph from a story by W. Cabell Greet, associate professor of English, Barnard College (and if possible, record yourself doing it).

Once there was a young rat named Arthur, who could never make up his mind. Whenever his friends asked him if he would like to go out with them, he would only answer, "I don't know." He wouldn't say "yes" or "no" either. He would always shirk making a choice.

What is the most important point in this paragraph? It's that Arthur could never make up his mind; the places in the paragraph that make that point should be emphasized. The others can be read at a fairly quick pace.

Vocal variety is one of the most powerful weapons in a speaker's arsenal; good speakers use it to great effect. If your words were written, you would rely on punctuation to move your thoughts along and to link your ideas. In speech, all you have to make your points and to get people to understand is your voice; it is the only sort of punctuation the speaker has.

An effective speaker stresses points by limiting the main ones and by shading all the rest through vocal technique. The key words you emphasize, the pauses you insert, your shifting pitch, rhythm, loudness, tone, and rate of speech all affect how your audience interprets your words. Learn to build; even lists can gain drama if you let your voice add it. For example, "I came, I saw, I conquered" could be said with equal emphasis on the three verbs, and it would seem rather bland. But "I came, I saw, (pause) I conquered" builds to a finale and catches the audience's attention.

You should always "lean" on the new idea in your sentence. For example, if you've been mentioning sales success and are introducing the concept of life success, emphasize the word life vocally, because it represents a new idea, and de-emphasize success, because you've said it already. Nine times out of 10 an action word (often a verb) represents the new idea; don't leave it entirely up to the audience to grasp the new idea just because it's new; use your voice to nudge the audience along.

Another way to highlight an important point is to stop talking just before you introduce the point. The pause is one of the most effective attention-getters around. People get so used to hearing a speaker talk that when there is silence they sit up and take notice.

Keep Your Speech Interesting Through Articulation, Diction, and Pronunciation

When you speak, you avail yourself of words the way a musician uses notes. And like the musician, you can sound words and letters smoothly or disconcertingly. All it takes to be smooth is some awareness of language. The way we speak breaks down into three elements:

Articulation means using your articulators - lips, tongue, teeth, lower jaw, upper gums, hard and soft palate, and throat - to form the sounds of speech. The key to good articulation is keeping all these parts flexible as you speak.

Diction is the total production of your sounds. You can be sloppy or crisp, depending on how you put everything together.

Pronunciation is the manner in which you deliver words; it's where you place your accent. People in different regions pronounce differently - car in New York becomes cah in Boston. I once heard a Russian woman deliver an address on the subject of nuclear power at a public utility. When she said mass (frequently), it sounded to those in the audience like mess and they were noticeably alarmed and confused.

The clearer your articulation, diction, and pronunciation are, the more in control - and the more powerful - you will appear to be.

Don't Ignore the Basics - Vowels and Consonants

Vowels are the music of our speech; they carry the tone and must be pronounced like the open and pure letters they are. Consonants are the bones of speech; they must be sharp and precise. Diphthongs are a union of two vowels that form one syllable, but that one syllable must be formed properly.

When forming all vowels, the tip of your tongue should be behind your lower teeth. The two major problems people have with vowels are elongating the short ones and not drawing out the long ones. Keep your jaw active and your tongue flexible and you will avoid these mistakes.

Practice: Explore the differences between "he bit the dust," where the vowels are short and clipped, and "the long sleeve," where the sounds should be drawn out.

Reading out loud is still the best way to become aware of the various sounds speakers face. Inside our small, 26-letter alphabet lurk a surprising variety of combinations. We have only five vowels, but 14 vowel sounds are possible. Our 19 consonants can produce 25 consonant sounds - like the "dg" in udge. The more aware you are of these components, the more practiced you are at uttering them, the more polished you will sound.

Vowel, Diphthong, and Consonant Exercises

Practice the following sentences, concentrating on the underlined sounds. If you have any questions about pronunciation, consult a pronouncing dictionary to help you understand what the sounds should be.

Breathe: Your Speech Depends on It!

For your audience to hear you, you must breathe correctly. People tend to start sentences on a high note and fade out; their voices start to sound monotonous because they don't have enough breath to support variety throughout the entire sentence. A good voice has sufficient breath so that the audience hears all the important sounds.

We get into bad habits and don't use our breathing fully. To really see how to breathe, watch babies or animals. To breathe fully, like they do, take a deep breath and observe yourself. Did you use only your shoulders and chest or did your diaphragm (the area just above your waist) expand too? As you inhale, your diaphragm should expand, and it should deflate like a balloon as you exhale.

Find Your Diaphragm

To get your diaphragm going, pant like a dog out of breath. Put your hand above your waist. Now, laugh - when you laugh you are actually breathing through your diaphragm. It's like a large band all around this area of your body. To exercise your diaphragm, lie down with an object like a heavy book pressing against your chest.

Practice: Raise the book up and down and get used to breathing through your diaphragm. When you're standing, practice not lifting your shoulders as you breathe: Proper breathing isn't seen or heard by your audience.

It's not just how you take in air, but how much. If you take in too much, you are going to flood your diaphragm; if you take in too little, your voice will sound very thin. You have to learn to distribute air evenly over an entire sentence, and it's a good idea to take in a little extra so you don't run out of steam. Because the most important point usually comes at the end of a sentence, you'll want to have enough energy to really make your point there.

Get into the habit of taking air in through your nose and letting it out through your mouth; this way your mouth doesn't get dry, which is a common speaking fear. Breathing through your mouth will only accentuate whatever dryness is already there.

Build Your Endurance

Short phrases only require short breaths. But complex sentences pose challenges for speakers who don't want to weaken points by stopping in the middle and gasping - however slightly - for air. You can control your need for air just as people train themselves to stay underwater for long periods.

Start by saying a short sentence first. Then add phrases one at a time while extending your endurance.

Practice: "This is the cow, with the crumpled horn, that tossed the dog, that worried the cat, that killed the rat, that ate the food, that lay in the house that Jack built." You can also use "The Twelve Days of Christmas." Each day you practice - and lengthen the sentence - your endurance grows.

Your Path to a Powerful Voice

Although there are many voice pitfalls into which we can fall without knowing it, there are also many steps that assure us of clear and effective communication:

Use a warm, resonant voice. Avoid sounding flat, gruff, harsh, too weak, or too loud. Strive for a clear, ringing tone and speak with vigor.

Build your point vocally. Add emphasis and drama through the way you actually say your words by stressing the most important words and phrases and shading the less important ones.

Vary your pitch, force, volume, rate, and rhythm. Catch people's attention by getting noticeably louder at an important point.

Have enough breath to finish each sentence on a strong note.

Make sure your thoughts forge ahead and build your argument.

Display a lively amount of vocal and physical energy. Be animated; otherwise, why should your audience be enthusiastic?

Use rhetorical questions to involve your audience, but don't overdo it.

Clearly articulate each sentence, phrase, word, and syllable. Give full value to all the sounds in your speech.

Do not drop consonants (for example, gonna, runnin').

Use correct pronunciation.

Strive for a smooth tone; it will sustain your argument better than a choppy one.

Avoid "oh," "uh," "okay," and "you know."

Make sufficient use of the pause.

Make sure your voice rises when you ask questions and falls when you make statements.

Use emphasis, pauses, inflections, changing pitch, and loudness to shade what you have to say.

A Quick Fix for Imminent Engagements

To guard against being boring, add variety to your next speech. Here is a quick list of things you can add without much trouble - things you should add to ensure that your next speech will be livelier than your last.

Put at least two rhetorical questions in your speech. Your voice will naturally rise when you come to them.

Insert at least one dramatic pause. This device builds your power, for nothing captures the audience's attention like silence.

Vary your speed. If you tend to speak quickly, slow down at least three times during your presentation; if you speak slowly, speed up at least three times.

Change your voice and your attitude just before your conclusion.

Combine an interesting variety of voice inflections within your speech to involve your audience. The next chapter goes into meeting those needs in detail. Adding variety to your voice is important in general communication as well. Colleagues will listen more closely when you color your words to give emphasis to your important points.

Relax, You Probably Sound Fine

Speaking well is an art, not a science, and there is no one formula for a compelling voice. Whether you tend to speak fast or slow, you don't have to completely change the way you present words. Just become aware of the little things you can do to change the way you sound and practice the voice exercises in this chapter. Then at your next presentation, be natural and be yourself.

Develop a 3- to 5-minute vocal warm-up for yourself.

Record your next presentation or record a practice reading. Then evaluate it using the voice and speech evaluation form below.

Read children's stories to your kids, to your neighbors' kids, to your nieces and nephews. Volunteer to read for the blind. Use your voice to its fullest. When you are a character, really give that person a unique vocal character. You'll have fun and so will your audience.

Rent or buy some books on tape read by excellent British actors. Good actors such as Anthony Hopkins and Maggie Smith utilize all kinds of vocal variety. These tapes will help to train your ear, give you confidence to expand your vocal range, and will also be enjoyable listening.