Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 24: Delivering with Style: Individually or with a Team

Charm is that extra quality that defies description.

- Alfred Lunt

Enthusiasm Can Make the Difference

My botany professor created my lifelong love of plants because he was so enthusiastic about his course from the very first day. On that first morning he literally jumped up and down and said, "Ladies and gentlemen, guess what I have here?" Shivering with excitement he handed us a leaf, saying, "It's a living thing." That kind of attitude is contagious; the best speakers are genuinely excited about their topics. They have passion and aren't afraid to let it show. They know they cannot be neutral or apathetic if their mission is to persuade.

Whether you're facing an audience, active questioners, your boss, or a potential customer, it is your lot that your words tell only part of the story; the rest lies in how it's told. No matter how powerful or persuasive your words, your delivery will make or break your speech. Body language makes an initial impression with your audience, but it's your own style of delivery that will continue to shape those impressions. I still remember that botany professor because the way he presented plants was passionate. Look around and listen, and I think you will find it's the passionate speakers who are the powerful ones.

Use enthusiasm throughout your speech. With your opening words, show enthusiasm for both your subject and audience. Let your audience know you are delighted to talk with them.

Real enthusiasm leads to vivid presentations and makes your speech sound fresh to each audience, no matter how many times you have given it before. And you should take advantage of every actor's secret - make each time you speak about something seem like the first time.

Build on Your Strengths

Just as we all have unique ways of walking, dressing, and talking, we also have a unique style of delivery. Videotape yourself giving a speech and look at how you delivered it. Look at four television interviewers with essentially the same job and see the huge differences in style: Oprah Winfrey, Barbara Walters, Charlie Rose, and Larry King all shape their shows around their personal styles.

The key to developing that style is to recognize your strengths and build on them. If you are a born raconteur, incorporate stories in your speeches. If you keep your friends amused and attentive with lively facial expressions and hand gestures, don't cut them out of your speech. Too much style can be distracting, and some speakers mistake it for substance. I am a very animated speaker and am aware that I sometimes have to tone down my gestures and movements. But for the most part, if you take advantage of your own natural style, it will enhance your relationship with your audience.

Establish Rapport

Somewhere in the opening of your speech you need to let your audience know who you are; each speaker does this in a unique way. Your audience already knows something from your appearance and your introduction, but you need to let down your guard and reveal something personal about yourself. It can be in the form of an anecdote, a humorous story, and so on. But it should be something they can empathize with. President Kennedy once endeared himself to the French people when he made a speech in Paris after Mrs. Kennedy had made quite a splash there. He opened by saying, "I'm the gentleman who accompanied Mrs. Kennedy to Paris."

By putting your experience into the context of your talk, you personalize it; by sharing that experience with the members of your audience, you interest them in yourself, which will leave them that much more attuned to your words.

The 4 Delivery Methods

Even though your confidence will grow as you get through your speech, the way it is received will hinge on the method you use to deliver it. There are four ways to deliver a speech: you can memorize it, read it, give an impromptu speech, or speak extemporaneously.

Memorization

Delivering a word-for-word memorized speech is very difficult, and I don't advise novice speakers to do it. Memorizing puts too much pressure on you, and unless you're an exceptionally fine deliverer, it will sound memorized. In many companies, people who memorize are much touted and I agree that it is impressive. However, in the final analysis, if a speaker is interesting and thought provoking, the audience doesn't mind if notes are used.

Professional speakers often memorize their speeches because they frequently use the same speech. Yet for each new audience they make cuts or additions and customize the speech. Only a very fine speaker can do the same speech over and over again and make it seem fresh each time. So unless you're a very proficient actor - or a politician whose every word will be analyzed in tomorrow's newspaper - don't memorize your speech. "He who speaks as though he were reciting," said Quintilian, "forfeits the whole charm of what he has written."

Reading

Reading a written speech has similar pitfalls. Unless your writing is superb and you are a true prose stylist, it's usually a mistake to read verbatim. Presidents of the United States are a notable exception, and they tend to have very good writers on staff. I once heard Jane Trahey, a gifted writer, make a keynote speech. Even though she read the speech, she made it work because her remarkable writing carried her delivery.

But most of us are not exceptional writers, and we stiffen up when we have to write something down. Lacking the confidence professional writers exhibit in their prose style, our written language becomes stilted. Compare a newspaper headline to the way you would relay news to a friend. In conversation we tend to be more natural, using shorter sentences, more colorful language, contractions, and slang. We're more informal and more interesting, which is exactly how a speech should be.

Another drawback of reading is that when you read your speech, you're communicating with the text instead of the audience. Novice speakers often believe that if they memorize their speeches by reading them over and over word for word; they'll be able to stand up and deliver the speech verbatim without reading. It's a great idea, but it just doesn't work. And if you practice by reading from a written manuscript, you will become so wedded to the paper that it is virtually impossible to break away from it. You also lose most of the expressiveness and engaging body language that make speeches work in the first place.

If you feel that you must read your speech, begin by talking it into a tape recorder; then type it up and read from that script - at least then the speech will sound like spoken language.

Impromptu

If you've become known as a speaker, people will sometimes ask you to stand up and give a talk on the spur of the moment. (And this can happen no matter what your status as a speaker is.) Bishop Fulton Sheen went so far as to say, "I never resort to a prepared script. Anyone who does not have it in his head to do 30 minutes of impromptu talk is not entitled to be heard."

Once you've had some experience speaking, you'll probably do a good job with an impromptu speech. Its elements are a condensed version of any prepared speech of general communication. The more you plan, prepare, and polish your formal presentations, the more persuasive you will be in all your communications.

Know your main point.

Know your purpose.

Work in a couple of good examples.

Try for a memorable conclusion.

Be sure to make a circle (relate your conclusion back to your opening). People always find this very impressive.

If you are known in a certain field, it's always a good idea to have a few brief speeches under your belt that you can deliver impromptu.

Extemporaneous

If you shouldn't memorize your speech, and you shouldn't read it, and you don't want to speak off the top of your head unless you absolutely have to, what is the best kind of delivery? The fourth kind - the extemporaneous speech - is the one that works best for almost every speaker. It means being very well prepared, but not having every word set. From the beginning, practice using notes, but never a typed script. The idea of practicing is not to memorize your speech but to become thoroughly familiar with the expression and flow of ideas. Don't memorize; familiarize. You can also prepare by reciting your speech into a tape recorder, using your outline to guide you. Again, talking keeps your speech fresh and helps you avoid the traps of written words.

Rehearse aloud, on your feet, at least six times. Edit your notes after each playback of the tape recorder. The more you rehearse, the better your speech will be. Those who knew Abraham Lincoln well said that the effectiveness of his talks was in direct proportion to the amount of time he spent rehearsing them aloud and on his feet.

Even when speaking extemporaneously, you should memorize certain key elements of your talk: the opening; the transition from the opening that takes you to your first point; every important transition that follows; and the conclusion.

Memorizing these parts ensures that you will know how to get from point to point and will help you maintain eye contact at all important moments.

When you speak extemporaneously, you incorporate techniques from the other kinds of deliveries. You end up committing certain parts to memory; you occasionally read a note from your note cards; and you may even throw in an off-the-cuff, impromptu remark. Because your delivery style is flexible, the speech can evolve, and you will still be comfortable and in control because you know where you're going and how you're going to get there.

"Confidence Cards": Aids to a Smooth Delivery

Many presentations with excellent content are less effective because the speaker uses notes that are either too skimpy or that contain every word of the speech. Properly used, note cards become what I call confidence cards: They add to a smooth delivery by helping speakers get from one main point to the next. Acting as cues, they contain your speech outline, notes to yourself, stories you will need to tell, key points and phrases, and reminders where to use your visual aids - anything and everything that will help you. And they save speakers from their greatest fear: forgetting what they're going to say next.

These cards - whether 3 x 5 inches or 4 x 6 inches - are easy to hold, don't rattle or shake the way larger papers do, and give an air of professionalism and preparation to your presentation. They are extensions of your own style because they only outline your speech, forcing you to talk in your own words. They also give you something to do with your hands. But you still need to practice your speech many times using the cards, or else you'll tend to go over the time limit or get off track.

Remember the following key points when using confidence cards:

Write so that you can see your information easily.

Make only short, key statements that will trigger your memory.

Number the cards once you have them all, to protect yourself from chaos if they fall off the lectern. Also, you may need to shorten your speech at the last minute, and you can do that by simply removing a few cards. If they are numbered you know just where you are at all times. To help you make last-minute decisions, try color-coding the ones you can eliminate if you need to.

Never read from the card. Glance at your notes and then speak to the audience to retain eye contact.

Note on the cards which visual aids you are using to develop the key points.

As you go through your note cards in your practice sessions, write little reminders on them: where you want to pause, where you want to smile, and so on. If you have trouble remembering to look around at the whole audience, you can use a card to remind yourself to take in all sides of the room. Confidence cards make excellent security blankets; don't hesitate to rely on them.

Confidence cards don't have to be actual cards. I've seen excellent speakers use a clip board. When I'm conducting workshops, I use a loose-leaf notebook that holds my script, which I place on a table in front of me and refer to from time to time. The purpose is to give you that confident edge and to help keep you on track.

How to Tailor Your Presentation by Size and Space

Many of us speak in such varied situations - to the decision-maker, one-on-one, in a boardroom to a decision-making group, and often to large audiences at company or industry conferences. Every time you present to a large, medium, or small group, you must alter your presentation to fit the number of people and the size of the room. While most of the techniques and concepts covered in this resource apply to all forms of speaking in all situations, there are some differences between speaking one-on-one, in a boardroom, and to thousands.

We'll take each speaking situation - large group, boardroom, and one-on-one, and analyze it in relation to preparation, stage managing, delivery, and visual aids.

Preparation

Recently, I observed a physician running a meeting for 25 in a hotel conference facility. Arriving late, she had little time to prepare or check the equipment or her microphone.

Microphones are very sensitive to other amplifiers. The attending audiovisual technician never turned off the wall speakers that were permanently positioned around the room. Every time she moved - even a step - the resulting feedback was so horrible that she was forced to speak without the mike. This diminished her impact vocally, for she had a soft breathy voice. She also appeared less prepared, thus further reducing her credibility.

Little things make a huge difference when presenting. Poor lighting, microphone feedback, and not having the proper markers can all have disastrous effects. All three speaking situations require preparation. The secret to being well prepared is to create a checklist, and ask questions.

Large Group: If using a TelePrompTer, you must follow it word for word - no ad-libbing allowed. Have your speech completely written out in a conversational style. Use contractions and short sentences. When I work with my clients, this is the most difficult part. Most speechwriters, even experienced ones, write for the eye, not for the ear. Use strong language and repetition for effect, and have a clear, organized pattern. Utilize rhetorical questions to keep your audience's attention, such as, "What are the real results of their innovative research?" If you're not using a TelePrompTer, there's no need to write out the speech. But it must still be well prepared.

Boardroom: Provide an intro for the meeting chairman (if there is one), so he or she can introduce you. You should always write your own introduction, but it is better to have someone else deliver it: your boss, the host, or a colleague. Find out how the meeting is structured. What's the protocol for questions? Who are the decision-makers and thought-leaders? Prepare for difficult questions and interruptions. Practice staying in control.

One-on-One: Your success here depends on how well you organize your time, and the clarity and specificity of your purpose. I have found that people do not put much thought into preparing for less formal meetings, when they think they can "wing it."

Stage Managing

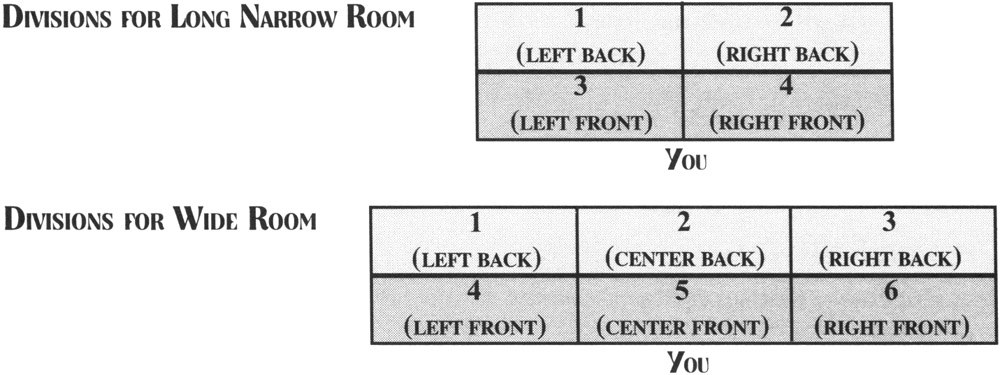

Large Group: You usually have less control over the environment when you're speaking in front of a large group. Make friends with the meeting planner, and he or she will help you. Ask lots of questions. Will the room be or wide or long? If you have a choice, go for horizontal seating: The sight lines are better. Lighting is essential. Do everything you can to not dim the lights. Use your LCD (liquid crystal display), computer, and any visual aids you deem appropriate. If you have to turn off the lights, be sure you have them turned back on periodically. Go early to your presentation area, or get a floor plan. The more you know about the setting, the space, and the lighting, the better. Know what's going to happen before and after you speak. Will you be speaking behind a lectern or on a podium? You can never ask too many questions. Have tissues, water, and a timer handy. Do not look at your watch. Make a complete checklist.

Boardroom: Find out in advance as many details as possible. Stand: you have greater impact. Find out how many people will be attending the presentation. Where will they be seated? Will they be wearing nametags? How will you identify each person there? Figure out the most beneficial placement for your visuals. Try to get an agenda, so you fully understand the flow of the meeting, and where you fit in.

One-on-One: Find out the setting for your presentation. There are many possibilities: office, small conference room, or restaurant. Pick the most advantageous setting for you. If you will be in an office, it's a good idea to use a desk for visual aids. Try using a desktop flipchart. If you need an outlet, find out in advance where one is located. If you need to do any projecting, be sure you have a clear white surface available.

Delivery

Large Group: Be aware of your visual impact; when communicating, your eyes are your most important feature. Use broad gestures and strong movement. Mentally divide room into sections, and try to cover all areas equally.

Get comfortable with covering the space on the stage. A microphone gives you a wonderful opportunity to use both the highs and lows of your voice. However, watch the tendency to sigh. Look for places to add vocal emphasis, and vary your pace. Move more quickly over less important information.

Boardroom: Curtail the broadness of your gestures to suit the smaller size of the room. If you don't have to cope with a large conference, a U is the best seating arrangement for this type of presentation, but be sure to "work the U." I recently observed a woman running her first major meeting and she had the room U shaped, but never really walked into the U. Using space efficiently is a wonderful way to demonstrate your confidence. If the seating setup is stationary, try to move around the large boardroom table, stopping to make key points. Establish eye contact with each person there. Use actual and rhetorical questions to help vary your voice.

One-on-One: Eye contact must be constant while using normal conversational gestures. Ask the right questions and listen. Don't spend too much time in chitchat. If you are at a restaurant, you will probably chat longer. But don't wait for dessert to get to the real business! Watch annoying vocal patterns ("Uh," "Okay," "You know," "So," and "Ah"). Bad habits are often magnified in less formal settings.

Visual Aids

Large Room: Always have an alternate plan. Pay great attention to lighting, especially if you will be using an LCD, or computer. When using a slide or LCD projector, the more powerful the projector, the stronger the image, and there is less need to lower the lights. Try to be in a room where the lights are controlled and there are none directly above the screen. This reduces the need for light dimming. Remember: Attention decreases in direct relation to intensity of light. Use bright colors, not dark, when creating visuals.

Boardroom: Try for multimedia - use computer-driven slides, plus flipcharts. Many of my clients have become fans of my two-flipchart strategy. I advise them to use two, with at least 10 feet or more between them. Flipcharts are the least problematic, most interactive, and encourage horizontal (side-to-side) movement. Horizontal movement engenders more interest than vertical (forwards-and-backwards) movement.

One-on-One: In this setting, brochures and product descriptions work best. Computers or desktop flipcharts can be used in an office. Be flexible and use what is available. If the office boasts a flip chart, use it!

Team Presentations

There may come a time when you are asked to give a presentation along with several other people. The advantages of team presentations are endless. Not only do you have the brains of many people, you also have the talents. If one person falls short in a certain area of presenting (for example, he isn't able to deliver financial reports and be engaging at the same time), another can pick up. But that doesn't lessen each individual's responsibility to the team. A team presentation can be quite a time commitment, but it is imperative to the success of the presentation that the group meet regularly to plan, to perfect, and to rehearse vigorously.

The Plan's the Thing

Without planning thoroughly, the group members will lose direction quickly. Without planning, it is easy to wind up with four separate presentations, rather than a strong cohesive one. When the group is together for planning, to ensure maximum success, these are the points to cover:

Purpose: Each person should be made aware of what the purpose of the team presentation is. It is important that they all be clear on why they are working together. This goes for the people who are assisting you behind the scenes.

Delegate Roles: The group should assess each member's abilities, strengths, weaknesses, and background. You would not want a serious, monotone speaker to deliver the rousing and memorable conclusion to a speech - the more energetic member of the crew should do that. Nor do you want the creative team member to be delivering the technical information.

Define Individual Purposes: Each team member, now assigned a different role, must develop (with the group) his purpose and how that contributes to the overall purpose.

Map out a Logical Agenda: It is time to decide who goes when and for how long. Keep in mind your audience, the group's time restraints, which part is most important, and what needs to be said.

How to Cover Introductions: You have a few options as to how you can introduce the speakers. You can introduce everyone at the beginning of the entire presentation. You can also wait until each presenter is about to begin his part of the presentation. Another way to handle the introductions is to briefly introduce everyone in the beginning and then do a more in-depth introduction as each person begins his section. Introducing a speaker right before his speech serves as a good transition between speakers. "Here is Joan Smith. She will enhance the points Jack made and how they apply specifically to your situation. She is highly qualified to do this because she was a client of ours and knows how this applies across the board" serves both as an introduction and a transition.

Visual Aids: All visual aids - for each person on the team - should look like they were designed by the same person. It is not good to have catchy, computerized visual aids for one person and hand-drawn transparencies for another. Be consistent! The most efficient way to accomplish this is to have one person designing all of the visual aids. This person can be a support staff member, or a team member, who is especially deft at graphics. The visual aids should have the same design and purpose, as the material allows. Go back to the chapter on visual aids and revisit the key points to make visual aids an integral part of your presentation, and not a distraction.

How to Handle Questions and Interruptions: It is good to maintain a consistency throughout the team presentation. A team captain should be in charge of the questioning procedure. He or she should field questions appropriately. Your group can accept questions all at once at the very end of the entire presentation, or they can accept questions at the end of each individual presentation. A more challenging option is to handle questions as they arise at any time during the presentation - this may be more desirable for a proposal presentation. The same applies for handouts and other interruptions - decide beforehand when and how handouts will be distributed and by whom. Also, are the audience members free to come and go as they please (this may be unavoidable in a client's busy office), or would you rather have them not be getting up and down during the presentation?

Plan Transitions: Transitions can make or break a team presentation. The audience should be able to easily follow the presentation and make the connection between each speaker and how he is contributing to the team presentation. Comfortable and impactive transitions ("or passing the baton") make the difference between a so-so presentation and an outstanding one.

Regular group meetings are a must and they should happen well in advance of the actual presentation. Team members should come to these meetings prepared to give a report on their progress; inform the group on the outline for their parts and any numbers, stories, or examples they will be using; and state how they will start and end their section. Each part should flow easily and subtly into the next section and these meetings are a time to make sure they do.

Rehearse, Run Through, and Repeat

Pay special attention to the introduction and conclusion of the entire presentation, not to mention the transitions between each section. Practice not only presenting the talk, but also the standing and moving. Team members don't want to be bumbling and bumping into one another - that looks neither professional nor organized. Audiences appreciate not only good verbal transitions, but they also appreciate good physical transitions. The more time you spend rearranging visual aids, microphones, and walking around one another, the more you are losing your audience's attention.

The entire team should be "onstage" throughout the presentation. Every team member must contribute and be supportive if the team is going to be a winner. If your listeners see one person presenting his section and his team members are off to the side not paying attention, they won't see this group as a team. Support each other at all times.

Test your presentation in front of an audience of coworkers and colleagues - as long as they are not connected in any way to your presentation. They must also be a group of people who will not feel hesitant about offering constructive criticism. Before you rehearse your presentation in front of them, ask them to write down their expectations of the talk. Afterwards, have an evaluation form on hand for them to fill out. Make sure it covers whether their expectations were met, what the purpose of the presentation was from their perspective, and if there was any information they thought was excessive or left out. Mention team members individually. Ask questions such as, "Were the transitions smooth?" "Did you understand who was speaking and why?" "Did you understand the purpose of each presentation?" Videotape the presentation and play it back, so you can see how you are perceived and fix any trouble spots.

The Telling Aspects of the Technical Details

It's not just what you say, it's what you use to say it. Visual aids are part of any speaker's style; if they aren't cohesive, they will reflect badly on you. Even the type of microphone you use will affect your delivery. A cordless mike allows you to move around and is a good choice for restless speakers. People whose delivery style is stationary will want a mike they can hold onto. As I said earlier, if you wish to appear intimate, speak softly and close to the mike. How you use the mike can become part of your unique style.

Be Powerful - Be Yourself

A good delivery does justice to the points you've gathered and to the speech you've worked hard to shape. It comes with practice and a lot of planning and from trusting and relying on your individual style. Don't try to adopt someone else's style; your audience will sense something is amiss, and you won't feel comfortable. If you be yourself and be enthusiastic, you will be well on your way to a stylish delivery, ready to use your delivery skills on a daily basis, starting with meetings.

If someone were to observe you, how would they define your style as a communicator?

What are your main strengths as a presenter?

Watch different newscasters for a week and define their delivery styles.