Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 2: How to Stand Up and Speak as Well as You Think

So now you've begun the process and have taken those steps outlined in the prior chapter. You're willing to face an audience but wouldn't refer to yourself as a pro. Then someone asks you to be a speaker at an upcoming event they are planning. Your first question springs up almost automatically: "What do you want me to talk about?" The answer is never really enough.

You will be given a subject and the setting will be explained, but that still leaves a lot of leeway in structuring your talk. You will be assigned a specific amount of time. Your role will be clear. But you will still have to prepare your talk, rehearse it, know it cold, and deliver it in front of a live audience. That involves a lot of work. Let's break the pieces apart and identify what you should do to give yourself the best advantage.

Preparation: Mental and Physical

In its simplest form, preparation is having done enough work to be absolutely sure you know what you are talking about.

Abraham Lincoln once said, "I believe I shall never be old enough to speak without embarrassment - when I have nothing to say."

Churchill said it took him six or seven hours to prepare a forty-five minute speech. It's no walk in the park. If you want to be confident, you must know that your message is worthy of the audience, worthy of the moment, and worthy of you. That takes time and it takes work. And it is worth it. Your sense of triumph at the conclusion of your talk will come, in part, from knowing that you have worked hard for this moment.

Know Your Subject

The first step in gaining confidence is to know your subject. There is no substitute for that. If you are not an expert on the subject, don't speak. You become an expert through study and experience. If you think about it, you may see that you are already qualified to speak on a number of subjects. Remember, someone else recognizes you as an expert and as a person who has experience worth sharing with a broader audience. That is why you have been asked to speak. But you still have to decide exactly what to say. The situation will usually determine the direction your remarks should take.

Know Your Audience

When Lincoln spoke at Gettysburg, he knew his mission was to commemorate those who gave their lives on that battlefield site. He spoke briefly but was so memorable that not only the battle but the speech have become part of our common history. The president of the United States speaks to the country and to the world on the state of the union, the budget, the economy, foreign affairs, etc. The president also speaks in response to any significant happening that involves the United States. These public addresses don't ramble (thanks in part to an army of crafty political speechwriters) and are to the point.

A department head in a company speaks both internally and externally on the mission of the department, or about a special initiative, an unforeseen emergency, in recognition of someone's accomplishment, or to announce a promotion, for example.

You can see that events and your audience often determine what is expected of you. Your responsibility is to reach into your own storehouse of knowledge and experience, determine your point of view about the issue at hand, and then craft your message so it addresses the current need.

Should You Write Out the Talk?

We live in an age where the computer is at our fingertips. We even use it to help us think. With that in mind, by all means, write out your talk. It will help you put your thoughts in order and your confidence will be buoyed by seeing the talk right there in front of you.

Then, read it over and over again. Read it out loud. Read it to your spouse, to a friend, to another family member, to your dog (if you can keep him sitting there, you know you are pretty good). Read it in front of a mirror while trying to maintain eye contact with yourself as you read.

Now you know the speech pretty well. Next, do the same talk without the script. Make notes if you like. Use them while you rehearse. On the day of your talk, you might even take the notes with you in your pocket to be used in an emergency, but leave the written script at home.

Never Read to an Audience

Never read a speech to an audience unless you are forced to do so. They deserve better and so do you. Think of your own experience. Have you ever been impressed when a speaker read a talk or a sermon to you? If your answer is, "No" (and I think it will be), then don't inflict the same pain on others.

We listeners are savvy folk. When a speaker begins a talk, the first thing we do is decide whether it's "live" (coming from inside the speaker's head) or it's "being read" (from a piece of paper on the lectern). They are not the same. "Being read" is "day-old bread." No matter how erudite the writing is, the audience sees the speaker as a reader of yesterday's news.

Did the Speaker Even Write the Speech?

An audience forced to listen to a speaker simply read notes may feel slighted or shortchanged. The drama is gone. We are not seeing the creation of a talk right before our eyes. We cannot even be sure the speaker wrote the speech. So we, fickle listeners that we are, will give the speaker demerits right off the bat.

But when a speaker begins a talk with head held high, looking at the audience as he speaks, we know that what we are hearing is "today's bread," baked fresh, right before our eyes. Our attention peaks. We are watching a live performance. We are impressed. The speech has hardly begun and we are awarding bonus points.

The Impact of the Audience

You walk to the front of the room and turn to face the audience. There is that superior force out there, staring back at you. Every instinct says you should scan the audience. Your eyes almost wander by themselves. That's their job - to scan for news, to take the news value out of the room. Eighty-five percent of all information stored in the brain comes through our eyes. The eye is our primary sense. "Let me serve you," says the eye, "let me scan."

But scanning also exacerbates a feeling of nervousness. Your eye sends all that blurry audience information to your brain, and the brain doesn't know what to do with it all. So it throws up an emergency flag and signals for an adrenaline fix. You already have that gnawing tension in your stomach, knowing you are going to have to speak. Then you get that extra jolt of adrenaline to really jazz you up. Your nervousness is increased. Your thoughts get all jumbled. Your mind can even go blank. Whoa, Nelly!!

Our Instincts Work Against Us

As speakers, what do we tend to do to combat all this? We slide into some pretty weak defensive behaviors:

Looking away from the audience when searching for a word

Looking at people without really seeing them

Looking up, hoping for divine intervention

Closing our eyes, briefly, when thinking

Sweeping the room with our eyes

These are habits, or quirks. They are not personality traits. They are not an integral part of your psyche. You do them because you don't know what else to do. None of it helps you think better or speak better. And the impact on an audience is negative.

Where Should You Focus?

Focus on one person, one pair of eyes. We call it "Eye-Brain Control." You remain focused on one person in the audience until you complete a thought. A thought is not a paragraph, it's a sentence or a phrase. It's a place in your dialogue where you might naturally pause. Usually it's more than five seconds but not as much as fifteen seconds in length. Then you move to another pair of eyes and complete another thought. You repeat the process over and over until you finish.

Does it work? Yes it does - better than any other remedy. Forget tranquilizers, alcohol, or hypnosis. The principle is simple, as are most great discoveries. When you focus on one person, you are reducing the audience to one individual. Your brain can handle that quite easily. Then you move to another individual. The situation becomes the same as what you face every day. You are used to speaking to one person at a time. You are good at it.

Eye-Brain Control - The Natural Way

It's so natural when you think of it. The eye can't focus on more than one person at a time anyway. When you look at your boss, you can't simultaneously look at his or her assistant. The second person goes out of focus. By using Eye-Brain Control, you are back to doing what you do best - talking one-to-one.

Benefits of this technique:

Gives you a way to control your nervousness

Helps you read your audience by seeing the reaction of individuals

Enables you to think better on your feet

Helps you control your rate of speech

Provides a way to cut back on non-words ("um, er," etc.)

What Adrenaline Does to Our Bodies

The eyes are only part of the solution, in cooperating with the great adrenaline rush we get when we stand in front of an audience. Our bodies are super-charged too. It's more energy than we are used to. If we don't know what to do with it, this physical energy can work to our disadvantage. It sort of leaks out all over the place. We fidget, clear our throats, put our hands in our pockets, move our feet from side to side, scratch our heads, play with a pencil, run an index finger across our noses, and cross our feet, among other things.

None of that helps. But the energy will have its way. You've got to do something. You can't store energy. You've got to use it or it uses you. So what do you do?

What to Do with the Energy

The answer is to use your body to add a visual dimension to the content of your talk. Gesture for emphasis. Gesture for excitement. Show physically that you believe and are committed to what you are saying. Increase your volume to add inflection and vocal emphasis to your message. That way, you use the energy productively. Let's examine this whole concept further.

Speaking to a group in its simplest form is . . .

Energy released (by the speaker) = Energy received (by the audience)

If we speak with low energy, the audience receives low energy, and our impact is reduced accordingly.

How a Speaker Impacts an Audience

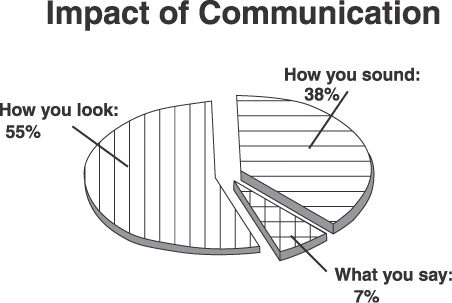

A few decades ago a famous UCLA professor, Albert Mehrabian, conducted extensive research on the communications process. The chart in Figure 2-1 is drawn from those studies.

Figure 2-1: The Visual Impact of Communications. Adapted from Nonverbal Communication, 1972 Albert Mehrabian.

What this chart shows is the relative impact of three factors when you speak to a group. How you look accounts for a whopping 55 percent. How you sound, 38 percent. What you actually say only accounts for 7 percent of the total impression you've made.

How you look includes your clothes, your facial expression, your stance, the leaning of your body, your hands, the way you move your eyes.

How you sound depends more on volume and inflection than the quality of your voice. Again, it's an impression.

Your words? Suppose you're trying to motivate a group of people and you tell them that something is "a great opportunity," but you don't look and sound it. They believe their eyes and ears, not your words.

How You Look

Let's examine some of the "how you look" mannerisms that can work against you when you face an audience (see Figure 2-2). Most of these are a result of trying to hold back and bottle up the adrenaline, the nervous energy that has been pumped into you to help you meet the challenge.

Five Ways to Lose Visual Impact

Figure No. 1: Hands in pockets tries to create a casual impression. This can have the opposite effect of making you look nervous. Also, it adds no plus value to your talk. And who said casual was a good way to look in front of an audience? You are much better off looking committed to what you are saying.

Figure No. 2: Guaranteed, if your hands twitch, opening and closing, everyone will notice. Don't forget, their eyes are scanning for news, too.

Figure No. 3: In this one, Velcro grabs your elbows and won't let loose. Your arms can't be fully extended because your elbows are stuck to your rib cage. You'll never be able to show how high is high or how wide is wide. Your gestures will be smaller, less interesting, and repetitious.

Figure No. 4: Some people say they like to move around. Imagine someone coming into your office and dancing around as they talk to you. Moving around only makes sense when you are changing location for a purpose.

Figure No. 5: In this picture the speaker has all the weight on one leg. Your energy is stuck, and your body knows it. If you tilt one way to release it, the audience wonders which way you will tilt next.

All of this nervous energy is leaking out; it is not helping you as a speaker. It is taking a slice out of the 55 percent segment (the "how you look" portion) of your impact.

What to Do with Your Hands

Where should your hands be? When you begin, they should hang naturally by your side. Then they should be used to describe and emphasize what you are saying. Ideally, you should gesture with one hand at a time. If you use both together, they will tend to work in parallel, cutting the air up and down as you talk. This is called indicative gesturing, which is repetitious and adds some, but not a great deal, of value.

When you are able to use one hand at a time, your hand and arm movements can be descriptive as well as emphatic. From an audience viewpoint, this provides an almost infinite variety of visual stimulus that increases your impact and helps reinforce your message.

Remember, the audience is looking with their eyes even more than they are listening with their ears. They want something to happen up there. You, as a speaker, must encourage their eyes to focus on you, if you are going to hold their attention. Otherwise their eyes will drift somewhere else. And wherever their eyes go, their minds will follow.

What about Stance?

Somewhere in your mind you may have a picture of a speaker pacing back and forth while mesmerizing the audience. Maybe it's the fictional Elmer Gantry or the very real Vince Lombardi. But it's a mental image that makes us think that pacing while talking is a plus. It isn't. Walking around is of no value to the audience unless you are going someplace. Pacing is going noplace.

You look strongest and in greatest control when you plant your two feet shoulder-width apart, weight equally balanced, square to the audience. That way, all of your energy manifests itself in gestures, facial expression, and upper body movements. Your message is reinforced and made clearer by your physical behavior. Your confidence will grow as you sense the control.

A popular misconception is that women should do it differently, with feet close together or with one foot placed slightly behind the other. Not so. These postures rob the speaker of the authority she wants to convey.

The Impact of Your Voice

If your volume is low, you are probably speaking in a monotone. If you are monotone you are boring (see Figure 2-3).

Most executives don't speak with enough volume. Their sound is too soft. This is true for females as well as males, upper level as well as lower level, all industries, professions, and the arts. You name it. Speakers think they are loud, but audiences don't. They think speakers are boring. They want more excitement, and volume is a big part of that.

Low Volume, Low Interest

Audiences read low volume as low conviction or low interest on the part of the speaker. Then they take a small mental jump and say to themselves, "If the speaker isn't interested, I'm not either." At that point you've lost them. Good-night, Irene.

Harry Holiday, the former CEO of Armco Steel, once said, "I think the greatest sin in business life is to be boring." Some people might argue with that, but I found it to be most insightful, as it pertains to public speaking. The greatest sin a speaker can commit is to be boring, because that loses the audience. Yet we see it all the time. Low volume is the greatest cause.

Should You Exaggerate Volume?

You may be thinking, "What are you suggesting - that I go up there and shout?" We're tempted to say, "yes," just to get the point across. But, then you'd say, "This is crazy," and stop reading.

All speakers think they speak louder than they do. That's only because they are hearing themselves through the bone structure of their head as well as through their ears. And many people have been taught that they should speak in a conversational tone. Unfortunately, that doesn't work when you are speaking to an audience. You will be trying to contain the adrenaline, to hold back the energy, instead of letting go and using it. You'll swallow your words. Your body will be a reflection of your weak voice. You'll be conscious of your nervousness. No good.

A Leap of Faith

But if you take a leap of faith and let your voice ring out, you'll find that your body will follow and your confidence will soar. You see, volume is a trigger mechanism. Once you push yourself hard for more volume, your body will say to itself, "Hey, wait a second. I'm just hanging out here not doing anything. Maybe I should dive into the fray and help get the message across."

Then you'll gesture, you'll emphasize more, your hands will beat the air, your face will contort a little bit to show feeling, you'll smile, you'll frown, you'll knit your brow, you'll smash one hand into another. Your voice will have character and timbre. Your speech will have passion. The audience will love it. And they will love you.

All of that will make you free. Free of fear, free of self-consciousness, and free of self-doubt. You will have taken all of that adrenaline, all that energy, and put it to work for you. Once you can do that, you will have found the "open sesame" to self-confidence when you speak in front of a room. Always remember: Your volume is the best physical trigger, the key to making it all happen.

Making the Most of Your Words

As Mehrabian notes, the actual words you speak will usually account for only 7 percent of what the audience will grasp from a presentation. But when you're speaking on the spot, and you've got to say it right, every word must count.

The Five Forms of Evidence

To speak successfully, you must provide some evidence to support or back up your viewpoint or your recommendation. It's the evidence that makes what you have to say interesting and believable. It's the evidence that makes the presentation persuasive and memorable. Let's look at the forms of evidence as they can be used for a talk. There are five of them, and they are easy to remember because when you put the first letters together it spells PAJES (an obvious misspelling of PAGES, but still a good mnemonic):

Personal Experience (The Story)

Analogy

Judgment of Experts

Examples

Statistics/Facts

Let's take the last one first. It's where many speakers concentrate, but it's not the best tool - it's just the easiest and most familiar. Most of us use Statistics and Facts really well. We are taught that's what business is all about.

But that's not what people are all about. They're about flesh and blood and feelings. Statistics and Facts aren't, but the other kinds of evidence are. Those are the tools to call upon if you want to get inside the minds and hearts of your listeners.

We'll tackle Personal Experience (the story) in depth in Chapter 4 and again in Chapter 16. Let's look at the other four, as they are applicable to nearly every situation.

Analogy is a form of evidence that is often neglected because it takes a little more work and more than a little creativity to come up with a good one. Yet a good analogy can have real power when used properly.

Let's define it: An analogy is a point of similarity between two unlike things. The one we are most familiar with is the "tip-of-the-iceberg" analogy. This implies a warning: It's about seeing only a small portion of something and missing the significance of the whole.

All good analogies are visual and allow you to exaggerate a point without offending the listener's intelligence. Analogies bite into a listener's consciousness. They register and they stay there.

Judgment of Experts is simply a supportive statement by a person the audience would recognize as an authority. You must explain the expert's credentials if they are not known to your listeners. For best results the quotes of another person should be kept short. Visualizing the quotes on projected slides will increase the power of the quote in supporting your presentation.

An Example is a specific situation with various key factors similar to those of your premise. Examples are persuasive to the degree the audience sees them as paralleling his or her own situation.

Statistics and Facts have their place, of course - especially if they are astounding enough to wake up the crowd.

Visualizing your evidence, whatever the form, will increase the power it has in supporting your presentation.

The Impact of an Analogy

Analogies can have amazing impact in any talk, in part because everyone understands them. Let's look at an example of that impact. Charlie Wend was CEO at a public relations company. Jill Westman was the company's top sales producer. Jill was also as bright and competent a person as you could ever hope to have on your team.

Charlie had an important administrative project that had to be thought through and a plan developed. Jill, because of her variety of talents, was the ideal person to do the job and do it well. So he called her in one day, laid out the project, and asked her to take it on.

Now, let's look at it from Jill's perspective. Jill was juggling the needs and demands of five clients and was about to land another one. She was on a roll as a salesperson and, given the time, could double the business she already had.

Jill listened attentively, asked questions, and agreed it was important. Then she said, "Charlie, are you sure I'm the best person to handle the project?" Naturally, Charlie assured her that she was and then said, "But Jill, I'm curious, why do you ask?"

Jill said, "Charlie, I see the importance of the project. There's no question that it has to be done and done well. And I'm flattered that you would ask me to handle it. But Charlie, I'm handling over a million dollars' worth of business right now, and I have that much more in new business just inches away, if I can get to it.

"If I take on the project you outlined, it would take half my time for two months, and I wouldn't be able to get to the new business at all."

Charlie expected this push back, so he said, "Jill, I admire you for what you are doing on the sales front, but we need this project done and you are the best person for the job."

Jill could see she wasn't getting anyplace, so she used an analogy. "Charlie," she said, "don't you see what you would be doing? Asking me to take on that project would be forcing me to cut back on my selling. It's like taking your best racehorse and putting a two hundred pound jockey on her back."

Charlie's Reaction to the Analogy

Charlie said afterward, "The racehorse analogy was so clear and so obviously valid that I agreed with Jill. I was resisting her arguments at first because I expected them, but we're in a sales race in this company, and I didn't want to slow down my best horse in that race."

Notice the mental picture Charlie carried away from that exchange. All new learning needs to find a way to connect to existing knowledge in order for it to be stored and retrieved for later use. That's one of the beauties of analogies. They make an easy connection to the audience's memory bank. And your listeners can play them back afterward, if necessary.

Key Learnings for Speaking as Well as You Think

Do:

Seek an opportunity to speak. Ralph Waldo Emerson said, "Do the thing you fear to do and the death of that fear is certain."

Prepare your talk, outline it, write it out, make notes, and wallow in the material. Rehearse it aloud until you are sick of it. Then go through it one more time.

Focus on one pair of eyes at a time when delivering your speech. Your butterflies will fly away.

Be physically dynamic. Use hands, gestures, and body to make your talk come alive. Your nervous energy will work for you, and you will soar.

Use analogies to support the points you are making. People remember vivid mental images longer than they remember words.

Speak up. Speak out. Speak loudly.

Don't:

Try to hold back or be reserved as a speaker. The maggots of nervousness feed on that, and they'll eat you alive.

Bring your hands together. Once you do, they'll establish a relationship and work in parallel. You need them operating one at a time to create excitement.

Think you can solve nervousness by reading your talk. It takes a lot of training and experience to do that well. And the audience doesn't like it when you do.