Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Part II: Delivering the Leadership Message

Part Overview

Once the message has been developed, it is up to the leader to disseminate it through words and actions. The ultimate test of the leadership points is the ability to deliver the leadership message with frequency, constancy, and conviction.

The chapters in Part II will help you amplify your message from concept to delivery and follow-through, chiefly by connecting with an individual or group through oral communications. The ability to stand and deliver either one-on-one or one-to-one thousand is the ultimate test of a leadership communicator. When communications is done correctly, people will be inspired to follow, and in the process will achieve inspired results for themselves, for the leader, and for the organization.

Chapter 7: Assessing Your Audience

Overview

To me, a ballpark filled with people is a beautiful thing. It's an epitome, a work of art. I guess I have seen everything in the country: Yosemite, Old Faithful, the Grand Canyon, and the most beautiful thing is a ballpark filled with people. Ballparks should be happy places.

Bill Veeck

Pat Williams with Michael Weinreb, Marketing Your Dreams: Business and Life Lessons from Bill Veeck, Baseball's Marketing Genius.

The executive had worked very hard on his presentation. He had been invited to be a guest speaker and receive an award for his services to the industry. It was a prestigious event.

So, as befit the occasion, the executive had collected his information; he had even hired a speechwriter to script the speech and a graphic services company to produce the visuals. He arrived early in the day to assess the room and even rehearsed on site. At the appointed hour, the executive was introduced, and he proudly took the podium. Looking out over the audience, he took a deep breath, smiled, and began his presentation. He was careful to note how proud he was to receive the award.

Everything proceeded well - for about 30 seconds. Then the audience began to grow restless, and after another minute or so it began a series of catcalls: "Come on. Hurry up. We're getting thirr - sty!" After another minute, individuals in the audience began to throw things. Bound and determined to be heard, the executive, like a St. Bernard in a snowstorm, plowed ahead. As the crowd grew more restless, he began to speak louder. When things hit the stage, he grew louder still, until after 3 minutes or so, he was shouting into the microphone.

Chaos ruled.

What went wrong? How could something that started so wonderfully and was prepared and rehearsed so carefully go so terribly wrong?

Simple. The executive had failed to assess his audience.

Not until later, when the speech was over and he had retreated to the safety of an anteroom, did the executive learn that he had been the only thing standing between the audience and the bar. It was the end of a long day, and the crowd of salespeople and industry representatives was in no mood for more talk. They wanted to "drown the day" with libations.

Dealing with Hostility

What can you do when you face a hostile audience? One answer is to retreat and live to speak another day. But there is another approach.

After the American Revolution, George Washington returned to his beloved Mount Vernon to farm. Despite the Americans' victory over the British, nationhood was still a thing of the future. The Thirteen Colonies had devolved into thirteen independent states, all bickering with one another. As a result of this disunity, the soldiers of the Continental Army had not received money for their years of service. At one point, a group of disgruntled officers gathered in Newburgh, New York, to plot a coup against the government in an attempt to seek restitution. Washington learned of the meeting and asked to speak to the officers.

When he entered the meeting room, he strode to the podium and looked out over the group. He knew most if not all of them, and he reminded them of the hardships they had shared during the long years of the Revolutionary War. He then drew out a letter from a member of the Continental Congress. He attempted to read it, then stopped and apologized. He said that not only had he turned gray while fighting for his country, he had gone nearly blind as well. He then reached to put on his spectacles.[1]

That gesture broke the ice. Washington again won the hearts and minds of his former soldiers. The coup was forgotten. Washington had defused a volatile situation by reminding the audience of their shared past and their shared values.[2] No speaker can do more. It was an act of courage; moreover, it was an act of leadership.

Washington had assessed his audience accurately, unlike our poor executive. To be fair, Washington had a previous relationship with his audience to draw upon, whereas our executive was a stranger to his. Washington had something upon which to build; our executive had nothing. Washington was right to persevere, whereas our executive should have departed quickly rather than try to talk over the disruption.

TV talk show host Oprah Winfrey is a modern master at assessing audience wants and needs. As an experienced presenter, she has a sixth sense for what the audience wants to hear. Her entire show is based upon meeting audience expectations for information, emotion, entertainment, and sometimes insight.

Just as presenters have expectations for their presentations, audiences have expectations of presenters. And there are things you can do to determine those expectations and prepare for them.

Find Out What the Audience Wants

The simplest way to find out what the audience wants is to ask in advance. If you are invited to present, take time to find out what the audience is expecting from you. Ask the individual who invited you. For example, if you are making a sales presentation, ask what kinds of features and benefits are most likely to be appealing to your audience. Does it want quality, efficiency, cost, or all of these?

If you are speaking to an internal group, find out what its issues are and find a way to weave those issues into your presentation. When you touch the concerns of the audience, you demonstrate that you understand its needs. Another means of determining audience expectations is to talk to people who will be in the audience. Find out what is on their mind. Think of ways to relate to their concerns without compromising your message.

Meet Audience Expectations

Every presenter has an obligation to meet the audience's expectations. In this regard, you are like a singer or a musician who is hired to perform. The audience may not be paying you in currency, but it is paying you with something more valuable - its time.

On the simplest level, audiences expect a presenter to show up on time and finish on time. Most speakers have no problem with the first part; it is the second part that can be troublesome. If you are asked to speak for 15 or 20 minutes, aim for 18 minutes. The audience will love you for it. I have yet to hear an audience complain that a speech was too short, but I have heard plenty of complaints about presentations that seemed to go on forever.

Keep in mind that you are speaking at the pleasure of the audience, not your pleasure. People can get up and leave at any time. Most of them will not do so, but they always have that option. Bill Veeck used public speaking as a tool to drum up interest in his ballclubs; he would speak anywhere anytime if he thought it would help sell tickets. But Veeck didn't just show up; as a natural raconteur, he provided entertainment in the form of great stories, often at his own expense.

Audiences expect presenters to be prepared. If you are a salesperson, know your product or service better than you know the floor plan of your house. Likewise, if you are a guest speaker, be current on your topic. Know of what you speak. Keep in mind how prepared Colin Powell is when he gives a briefing; he knows the facts cold. The same is true of Rudy Giuliani. They are leaders who know the issues and can speak to them.

Audiences expect presenters to talk to them, not at them. If you are delivering a call to action, invite the audience members in. Don't order them to act. If you are preaching a message, speak as a member of the congregation, a sinner like all the rest of us, not as some anointed prophet. To paraphrase an old saying, "You will attract more followers with an acknowledgement of personal weakness than with an attitude of self-righteousness." One of the most saintly humans of modern times, Mother Teresa, never spoke of what she was doing for others; instead, she always invited people to share in the work that needed to be done for others.

And finally, audiences expect messages that are in tune with their wants and needs. Salespeople need to meet this expectation exactly. Others, however, can deviate somewhat. Often the presenter must deliver a tough message about hard issues, e.g., a corrective measure, a quest for improvement, or the big one - the need for change. Messages like this make us feel uncomfortable, so it is up to the presenter to find a way to make the message amenable without changing its content. A sure way to do this is to appeal, as Washington did, to a shared past and an attitude that "we are all in this together."

It is necessary to point out the difference between relating to the issues and pandering to the issues. Relating implies empathy; pandering implies playing to. For example, when Lyndon Johnson spoke about his plans for the Great Society, he touched upon his experiences as a poor boy growing up in Texas. He said he understood what it meant to have very little and how important government assistance was to those who had nothing. His themes related to the themes of those he was trying to persuade. By contrast, Joseph McCarthy stirred Americans' fears of communism by playing to their baser instincts of hatred and exclusionism. He lowered the level of debate rather than elevating it.

When you relate to an audience, you do not need to tell it what it wants to hear. You strive for the truth, but you present it in a way that is credible and understandable. At the same time, you need to avoid preaching or talking down to the audience. Both can be equally irritating to an audience.

Overcome Objections within the Presentation

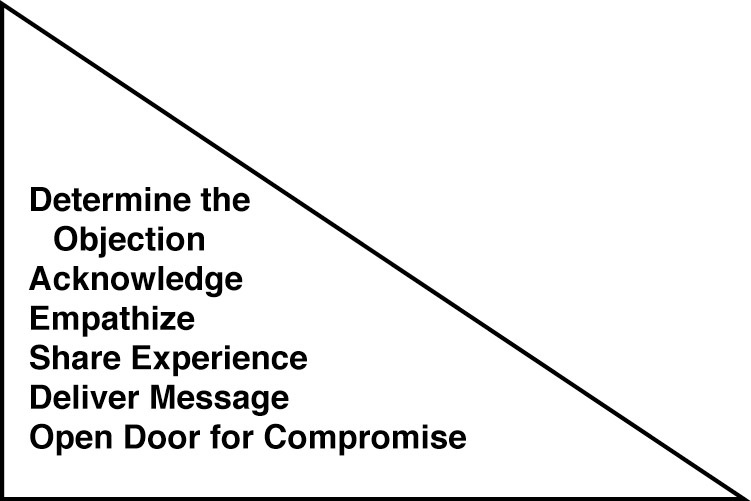

Facing a tough audience is not easy. But let's face it, sometimes it must be done. Management must talk to unions. Politicians must face voters. School boards must face parents. And so on. Not everyone wants to hear everything that you as a presenter have to say. Anticipating objections is part of the presentation process. If you follow the Toulmin argument process, you can formulate your rebuttals using the claim-reason-warrant methodology (see Chapter 6). With that in mind, here are some tips you can use to prepare yourself for those tough situations (see Figure 7-1).

Determine the objection. Isolate the "hot potatoes." Before you stand in front of the audience, find out possible issues or concerns the audience may have with you or the organization you represent. Vince Lombardi was a hard-nosed coach. He knew that players would initially resist the kind of discipline and hard work he would impose, but this did not stop him from getting his message across. He would deflect objections through implication: If the individual players did not adhere to the regimen, they would be gone. If you are a salesperson, you need to know the account history before you try to sell. For example, if the salesperson before you was a jerk, your audience may harbor negative views about you. You need to know this before you walk into the room. Likewise, if you are an executive addressing a group of frontline employees, you need to know their concerns about their work, the management team, and possibly yourself.

Acknowledge the issue. Say the issue out loud. If it is poor product quality or a tough question regarding management, spell it out - e.g., "I know you have an issue about this." As a former prosecutor, Giuliani was accustomed to dealing with objections. As mayor, he would freely give voice to the opposition as a means of acknowledging dissent. In doing so, Giuliani demonstrated that he was informed on and involved with the issues, even if he did not change his mind.

Empathize. When issues on are the table, communicate your concern. This does not mean that you say whatever the audience may want to hear, it means that you demonstrate concern - e.g., "I understand the issues you are facing." With guests on her show, Oprah oozes sympathy in a way that gets the guest to open up and share a personal moment that will enable the audience to understand an issue more vividly and sometimes viscerally.

Remind the audience of shared experiences. If you or your organization has a prior relationship with the audience, mention it. If it is a good relationship, say so. If it is one that soured, say so. The audience expects you to be honest. At Newburgh, Washington established the shared experiences at the outset. Katherine Graham made the Washington Post her life; her communications emerged from that commitment. Everyone who was part of the company understood that she stood for journalistic excellence and that by embracing that premise they could share in the enterprise.

Deliver the message. Once you have laid the groundwork for your presentation through acknowledgement and empathy, you are ready to move into your message and deliver your content. You are free, however, to emphasize or deemphasize according to audience expectations; in this way, you remain responsive to audience needs. Actor-director Robert Redford is accustomed to fighting battles over causes he believes in. His public speeches, together with his professional commitments, give him a platform upon which to stand tall on an issue, even when he knows that people can and will disagree with him.

Open the door for compromise. If the issue you must defuse is potentially divisive, you may wish to create a forum for compromise. Your presentation then becomes the first step in the healing process. You are entitled to present your views, but if you expect to create an action step - e.g., a sale or a dialogue - you need to open the door for action, that is, what's next? As a manager of 25 highly talented baseball players, Joe Torre lives by the art of compromise. He uses his communications to smooth over disagreements and open the door for cooperation. If you get beyond the objection, you can talk about how you would like to be part of the solution. You would like to help bury the hatchet and work out the issues together.

The good news is that when you can overcome objections within your presentation, very often you will win the audience over to your side and it will be receptive to your message now and in the future.

Create a Relationship

If you get beyond the objection, you generate an opportunity for a relationship. The relationship may last only as long as the presentation, or it may last far longer. Relationships emerge from a community of understanding and a sense of trust. To use a gardening analogy, relationships do not bloom overnight, but they can emerge over time if the ground is made fertile and adequately watered. Oprah has taken the relationship with an audience to an all-time level; over the decades she has been on the air, she has forged a bond with her audience, which has come to understand her as someone who reflects its issues and seeks to make the world better for it.

Both the success of your leadership presentation and your personal credibility depend upon assessing audience expectations. You can establish a relationship only if you demonstrate that you understand and acknowledge audience issues.

Bill Veeck - Master Promoter

When you look at Major League Baseball today, you would be hard pressed to find another business whose practices are so diametrically opposed to the needs of its customers - the fans. As owners and players regularly accuse one another of escalating levels of greed, it is the fan - the one who pays the escalating ticket prices - who gets left out in the rain like the family dog as the two sides bicker among themselves. In moments of despair for the National Pastime, it is useful, and hopeful, to recall that while owners and players have always been adversaries, there was one man in the game who marched to a different drummer - his own! He was Bill Veeck, and the cadence he marched to, wooden leg and all, was the same as the fans'. He loved the game as much as they did because first and foremost he was a fan himself. He was also passionate, opinionated, fun-loving, and dedicated to the value proposition "If you don't think a promotion is fun, don't do it!"[3]

And for an owner and baseball executive who had teams that finished first as well as last, no one ever had more fun than Bill Veeck. He was one part P. T. Barnum and one part Sam Walton - a combination of showmanship and customer value. Along the way, he irritated the plutocrats running the game and delighted the crowds who filled the stadiums. In his own unique way, Veeck was a leadership communicator who lived and breathed a message of honesty, integrity, and entertainment.

Born into the Game

In a game going back nearly a century and a half as a professional enterprise and noted for its characters, Bill Veeck was unique. When he was 3 years old, his father became general manager of the Chicago Cubs. Veeck grew up in the game; in fact, he planted the ivy that adorns the brick walls of Wrigley Field. Later, as a junior executive in the organization, he ordered a new scoreboard, and when it wasn't finished on time, he hired a crew - and rolled up his sleeves - and assembled it in time for opening day. True to his character, Veeck paid the inventor in full even though he had not completed the scoreboard on time. But Veeck also was a businessman. When the inventor wanted to bid on the exploding scoreboard for the Chicago White Sox many years later, Veeck said no.[4]

The Stunt

The stunt that transcended baseball and won Veeck a place in American mythology is the one involving Eddie Gaedel. As Veeck tells us in his autobiography, in 1951 he was the owner of the St. Louis Browns, "a collection of old rags and tags . . . rank[ing] in the annals of baseball a step or two ahead of Cro-Magnon Man." Looking for ways to get fans to the park, Veeck hit on the idea of hiring a midget to pinch-hit. He signed Gaedel to a contract and assigned him the number 1/8. Eddie walked on four pitches and into the history books, taking Veeck along with him. "I have always found humor in the incongruous, I have always tried to entertain. And I have always found a stuffed shirt the most irresistible of all targets."[5]

Veeck was not one to exploit the misfortunes of others. As one writer put it in the introduction to the re-release of Veeck's autobiography, Veeck - As in Wreck, now back in print 40 years after its first printing in 1962, "Physically, of course, Bill was not all there. His body was a mosaic of broken parts on borrowed time."[6] He wore a prosthetic leg, the legacy of a war wound suffered as a Marine in the South Pacific in World War II. The leg, along with his "impish smile," became his trademark.

Excellent Communicator

Veeck knew his fans not simply because he was one, but because he spent time with them. Stories of him sitting in the stands with the paying public at Wrigley Field or Comiskey Park are legion. He was accessible. Another way he stayed in touch was by speaking frequently to groups in his market area.

Bill Veeck would never win an award for his presentation skills; however, his speech teacher in college said that despite breaking all the rules for giving a good speech, Veeck was effective.[7] Pat Williams, a sports executive and speaker in his own right for whom Veeck was something of a mentor, attributes Veeck's speaking success to his storytelling and his humor. His standard opening line was, "I used to own the St. Louis Browns, and I'm not used to seeing so many people gathered together like this."[8] Famous for not wearing a tie, he once addressed a formal dinner where the men were dressed in tuxedoes: "First time I ever saw 1500 waiters for one customer."[9]

Veeck was also a "really good writer," says his coauthor, Ed Linn, who edited Veeck's copy. Aside from Veeck's autobiography, the two of them wrote Hustler's Handbook, which is considered the "virtual bible on sports promotion."[10] A compendium of tricks and insights for bringing fans to the ballpark, it is also a good read, chock full of good stories. Later Veeck became a columnist for the Chicago Tribune and USA Today. As Pat Williams says, "The reason [Veeck] wrote so prolifically and so well was because he had so much to say. Just to listen to the words pour forth from the page was an engrossing journey into the complexities of his mind."[11] An indifferent student, Veeck was an autodidact who loved to read; in the process, his span of knowledge became encyclopedic and he was able to converse learnedly on literature, history, tax law, and even gardening.[12]

Promotion as a Core Value

Promoting the product was what Bill Veeck was noted for, and his ideas for promotions were as broad and diverse as his reading habits. Veeck was the first to give away free bats, and his reach in promotion knew few limits: free balls, free pickles, free hot dogs, free lobsters, free ice cream, and then . . . free tuxedo rentals, along with pigs, chickens, mice, eels, pigeons, ducks, and, yes, 50,000 nuts and bolts.[13]

And this is only the free stuff. Veeck did more than freebies; he was the impresario of event packaging - Squirrel Night; a bicentennial-themed opening day in 1976; Music Night with free kazoos; special games for A students, teachers, bartenders, cabbies, and transit workers; and even Disco Demolition Night. (Well, even Veeck might go too far once in a while.)[14]

Veeck's promotions revolved around a desire to tickle the imagination. "You give away a radio or a TV - so what? What does that do for the imagination? Nothing. . . . If I give him 50,000 nuts or bolts, that gives everybody something to talk about."[15] And Veeck knew that when people are talking about your product, they will be more inclined to pay money to come out and see it. Veeck's promotions sprang from his values; he was a "giver."[16] He wanted to entertain his customers, and he wanted them to have something extra in return for their patronage. Veeck's final bit of advice on promotion was, "No one has a monopoly on ideas. You can always think of something."[17]

Grand Stage

Upon the death of Bill Veeck in 1986, Tom Boswell, baseball writer and thinker for the Washington Post, wrote: "Cause of death: Life."18 Not a bad epitaph for a man who loved and lived life to the fullest and brought us along for the ride.

[1]The story of George Washington quelling the officers' rebellion at Newburgh, New York, was based on The American President, Episode 7, "The Heroic Posture," written, produced, and directed by Phillip B. Kunhardt, Jr., Phillip B. Kunhardt, III, and Peter W. Kunhardt, a co-production of Kunhardt Productions and Thirteen/WNET New York, 2000. [The series was based on Phillip B. Kunhardt, Jr., Phillip B. Kunhardt, III, and Peter W. Kunhardt, The American President (New York: Putnam Publishing Group, 1999).]

[2]Ibid.

[3]Pat Williams with Michael Weinreb, Marketing Your Dreams: Business and Life Lessons from Bill Veeck, Baseball's Marketing Genius, p. xiv.

[4]Bill Veeck with Ed Linn, Veeck - As in Wreck: The Autobiography of Bill Veeck; reprint, with a foreword by Bob Verdi.

[5]Ibid., pp. 11-23.

[6]Ibid., p. 7.

[7]Williams with Weinreb, Marketing Your Dreams, p. 173.

[8]Ibid., pp. 173-174.

[9]Ibid., pp. 171-172.

[10]Ibid., p. 161.

[11]Ibid., pp. 161-162.

[12]Ibid., pp. 152-165.

[13]Ibid., pp. 192-211.

[14]Ibid., pp. 192-211; in particular, p. 201.

[16]Ibid., p. 201.

[17]Ibid., p. 209.