Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 8: Delivering the Message

Overview

Real communication is an attitude, an environment. It's the most interactive of all processes. It requires countless hours of eyeball-to-eyeball back and forth. It involves more listening than talking. It is a constant, interactive process aimed at [creating] consensus.

Jack Welch

Stuart Crainer, Business the Jack Welch Way: 10 Secrets of the World's Greatest Turnaround King, p. 107.

She was not beautiful. She was overweight. She was confined to a wheelchair. And she was one of the most dynamic speakers of her age.

Despite her cosmetic challenges, Barbara Jordan had the voice. You only had to hear it once to never forget its powerful resonance. Her diction was always precise, clear, instructional, and at times reverential. She spoke with the conviction of a preacher, but the insight of a scholar. Born to a poor black sharecropper, she earned a law degree from the University of Texas and became a law professor there. She represented her Texas district in Congress in the 1970s and served for a number of terms until her health forced her to retire.

The important thing to remember about Barbara Jordan is that she was a speaker's speaker. Where others are professional, she was artful. Where others are sincere, she was passionate. Where others are intellectual, she was a scholar. Where others are sensitive, she was human. And it is important to remember that while at first glance she might appear to be something other than what she was, the moment she spoke was the moment the audience listened.

Her eloquence was particularly piercing during Watergate. She sat on the Impeachment Committee that weighed the evidence against President Nixon. In those dark days of government, her words and her voice served as reminders that one of the strengths of our country is its adherence to law and the pursuit of justice.

When Congresswoman Jordan spoke, she created moments of truth. These result when a speaker's message and content meet the expectations of the audience live and on stage for all to see. How can you prepare for such moments of truth? Well, as the old man said when asked the way to Carnegie Hall, "Practice, practice, practice!"

The Authentic Presenter

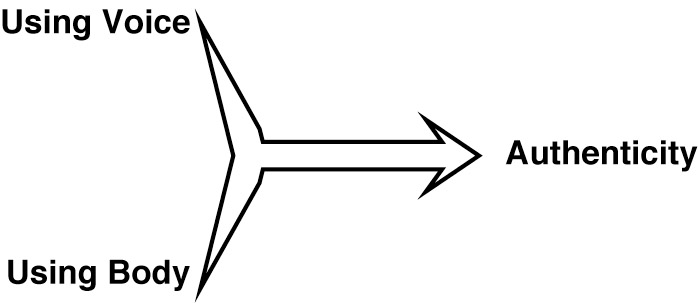

Establishing credibility is fundamental to leadership. As we have discussed, leaders affirm their believability through the content of their leaership messages. Vocalization of the message also plays a role; in other words, the way you look and sound as you present is critical to your credibility (see Figure 8-1). Emerging leaders often ask their speech coaches or trusted advisers how they should present. The answer most often given is, "Be yourself!" This is the correct answer, but it doesn't tell the whole story. The leader must be him- or herself on stage or in a coaching session, but he or she may also need to do more. Here are some suggestions:

Reflect the mood of the moment. Know the situation. Is the organization upbeat and optimistic, or is it fearful and dreading tomorrow? Take your cue from the mood and adjust your presentation style accordingly. For upbeat audiences, a lighter approach is acceptable; for uptight audiences, being direct and to the point may be more appropriate. Humor, however, can be a terrific way to lighten the mood and break the ice.

Emulate, don't copy. Be the speaker you are. Do not try to replicate some orator from the past. Use your own words. It is okay to quote, but do not try to copy the manner and gestures of someone else. You will only do yourself a disservice and raise questions about your believability.

Act the part. Speaking out loud, as discussed earlier, is acting. It is the art and practice of giving voice to your thoughts and words as a reflection of your leadership style. Sometimes women feel that they must raise their voices if they are to be heard, but instead of just being louder, they may come across as shouting. This situation plays into the stereotype of male speakers being more authoritative than female speakers. The truth is that men and women are equally believable or equally disingenuous as speakers, depending upon their ability to communicate the authenticity of their messages. Using a microphone will enable the speaker, male or female, to speak in a voice that captures his or her natural cadences and voice colorations. And don't hide behind the podium; use a wireless microphone so that you can stride across the stage or walk among the audience as you speak.

Take the message, not yourself, seriously. Audiences love it when the speaker shares something of her- or himself. Self-deprecation, or making a joke at your own expense, is a great way to connect. You can be serious about the message without being strident and overly intense in your presentation style.

Effective leadership communicators need not be polished orators. Winston Churchill was an accomplished master of the art form, but Katherine Graham had to force herself to become a public speaker. Both, however, radiated conviction in their communications.

The Authentic Coach

Not only is authenticity essential in the public forum, but it is equally important in private. Being themselves in a one-on-one coaching situation may be easier for some leaders than presenting to an audience because the intimacy of the moment is closer to the way we communicate in our daily lives. Some of us are more comfortable than others in interpersonal discussions. If the leader is naturally shy in such situations, he or she must find ways to overcome this. Leaders owe it to their people to be honest and direct, especially when delivering constructive criticism. (For more on coaching, see Chapter 10.)

Using Your Voice

Your most valuable asset as a speaker is your voice. Effective speakers vary the pitch and inflection of their voice for emphasis. Think about all the monotone lectures you had in college. Remember how boring they were? One reason was that the professor never varied his or her tone of voice. Big points melded with small points into some kind of tasteless stew of ideas that never boiled, never simmered, just remained lukewarm. And was forgettable.

But with practice, you can move to the head of your class by putting some zip and zest into your voice. Here's how.

Give voice to your voice. Practice using rising and falling inflections for meaning as well as for questions. Inflection is a form of audio punctuation. Use it!

Hear your message. Record yourself speaking. After you get over the hurdle of what your voice actually sounds like (trust me, everyone hates the sound of his or her own voice), listen to what you are saying. Ask yourself:

How am I using inflection?

Do I sound credible?

Would I buy from this guy?

This final question applies to everyone, not just salespeople. As presenters, all of us are pitching something, so we need to ask whether the audience is buying it, i.e., is receptive to the message. When speaking about Sundance or his commitment to the environment, Robert Redford employs his actor's ability to reflect his conviction through his voice. You recognize his sincerity in an instant.

Using Your Body

Much discussion has been devoted to shaping your content and delivery. Most of what we have explored thus far involves the mental processes of thinking and writing. However, the physical process is also important. Unless you plan to deliver the presentation as a disembodied voice from behind a curtain à la The Wizard of Oz, you need to put some physicality into your speaking. Steve Jobs is an accomplished public speaker. Strolling or even prowling the stage, alone or with a strategic prop (a new Apple product), he projects a sense of confidence and knowledge. His physicality underscores the power of his message because it says subconsciously, "I know what I am talking about and I am in control."

Visualize a speaking style. How do you see yourself delivering the presentation? From behind the podium, walking the stage, or moving into the audience? Ideally, polished presenters do some roaming. But until you are totally comfortable, it is better to use a podium where you can mount your speech or notes. Teleprompters, where words are projected on television monitors out of the audience's sight line, free the speaker to wander the stage without having to refer to notes.

Get involved physically. At a minimum, you must do a few simple physical things:

Make eye contact with the audience.

hift your gaze from one side of the room to the other and from back to front. Actually, the process is remarkably similar to the one you use when you drive as you shift your gaze from the road in front of you to the rearview mirror and sideview mirrors.

Look up from the podium. Keep your nose out of your notes.

Do not read the words in your visuals (if you have them). Instead, interpret what it is you have to say. (An exception is cartoons. They are little stories, so it is acceptable to read them.)

Use gestures for emphasis. Use a hand motion or wave an arm. When you are more accomplished as a presenter, get out from behind the podium. Move about the stage or speaking area.

Get your shoulders in motion.

Stand still momentarily, then stride to one side of the room.

Make grand gestures occasionally.

Engage the audience with an occasional question, e.g., "Wouldn't you agree?" or "Am I clear?"

If all of this sounds theatrical, that's because it is. If you do not feel comfortable doing it, then do not force it. Too much animation is wearing not only on you, but also on an audience. But gradually, over time, you can get physical to a degree that is comfortable for both you and your audience.

See your message. Videotape yourself. Again, you won't like yourself on the screen at first. But when you get over that, ask yourself the following questions:

Am I gesturing appropriately?

Do I look credible?

Would I buy something (a message or a product) from this guy?

The success of a presentation depends upon its delivery. Talk show host Oprah Winfrey radiates empathy and understanding. Rosabeth Moss Kanter, a professor, radiates energy and the enthusiasm of having something important to say. When the words match the voice and body, magic can occur. It is a matter of practice and commitment to giving the audience something it can remember.

Rehearsal: Putting Content Together with Voice and Body

No one likes to rehearse. Frankly, it is a pain. And with all the work you have put into the presentation, you know the material, so there's no need to worry. Right?

Wrong!

Rehearsal is important to the success of the presentation. Delivery is where the content meets the audience. Essentially, you are taking a two-dimensional presentation of words and pictures and moving it into three dimensions by the addition of yourself. You are adding life to the presentation. In this instance, you are the actor. And, to be blunt about it, actors rehearse.

Before you rehearse, take a good look at the room, starting from the rear. If you stand at the back, you can judge for yourself how large or small you will appear. Keep that in mind. If you plan to reveal something small, make certain that everyone can see it, or else don't show it.

Then go to the stage and take a moment to get familiar with it. Where will you enter? Where will you exit? If you have visuals, where will they be? Then go to the podium; how does it feel? Adjust the microphone to your height. That way you can walk right up and speak. (If you have to adjust it in real time, do it. Don't try to talk without one.)

If time permits, run through your entire presentation, complete with visuals. Practice as much as you can. After your rehearsal, thank the stage crew, if there is one. Your friendly demeanor can do a lot to improve the mood of the crew. Treat the crew members respectfully and they will do wonders for you. Then walk away. If you are happy, get a good night's sleep. Read over your speech in the morning and maybe practice in the mirror. Focus on the outcome and relax. You are ready to stand and deliver.

A note about using a teleprompter. A teleprompter (a term that has come to mean any form of prompting device that projects words in front of the speaker) is an aid that many speakers use. Used well, a teleprompter is a godsend. It helps the speaker look at the audience and still keep his or her place in the text. Used poorly, it can be as restrictive as a straitjacket on a mental patient. There is an art to using a teleprompter, so if you have never used one, practice with it first. If you are unsure about it, decline it unless you have a couple of hours to practice. (If you use a teleprompter, you will need to get your text or notes to the teleprompter operator in advance, preferably in computer form, so that the operator can enter and format it for you.)

Sell the Message

Part of delivering the message involves selling it - putting something of yourself into the message. In Chapter 4 we discussed marketing the message, finding interesting and sometimes novel ways to distribute it through different channels. Selling the message is about persuasion and conviction, putting the leadership commitment into it. Failure to do so can be hazardous, as Senator Trent Lott discovered on the eve of becoming Senate majority leader. In the wake of publicity about his offhand remarks in praise of fellow Senator Strom Thurmond's failed 1948 presidential bid on a segregationist ticket, Lott repeatedly tried to apologize. To many, his remarks seemed to lack sincerity and even credibility, given that he had made similar statements in the past. Lott was criticized by politicians on both sides of the aisle and rebuked by President George W. Bush. (As a result, Lott resigned his leadership post prior to assuming it.)

In contrast, watch a successful salesperson make a sale. She is fully engaged; she knows her offering and can make it come alive for the prospect. More important, she is attuned to the prospect's slightest nuance - a raised eyebrow, a glance at a watch, a look of consternation, a breaking of eye contact. These are telltale signs that the prospect is otherwise engaged and that unless the salesperson acts quickly, she will lose the sale. So what does she do? She shifts gears and tries another approach: asking a question, mentioning another feature, demonstrating a key benefit. She works the prospect, looking for signs that the message is reaching home.

Effective leadership communicators do the same. Whether it is Rudy Giuliani or Jack Welch, Mother Teresa or Shelly Lazarus, the communicator reads his or her followers, looking for signs that the message is being received loud and clear. When delivering a message, either one-on-one or to an entire group, the leader can judge for him- or herself whether the message is hitting home. Are people looking at the clock, looking concerned, or just not looking at all? Good communicators, like good salespeople, can shift gears and, like actors, find new ways to connect. How? Here are some suggestions:

Ask questions. If you want to know what is on people's minds, ask them. Good leaders are always asking questions as a means of gauging interest as well as finding ways to connect the offering to the individual. Engage the people in your audience in conversation. Find out what they are thinking. And don't be afraid to ask for feedback; it's important to know how you are coming across.

Make the benefits real. People need to see, hear, and experience the leadership message. The leader needs to connect the message to the individual. Show each person how what you are asking her or him to do will benefit her or him personally. Rich Teerlink made the benefits of a transformed Harley-Davidson real to employees, dealers, and customers through constant repetition. Give people a reason to believe, and they will. Human nature predisposes us to belong to something larger than ourselves.

Echo the values. All communications from the leader need to echo the values of the organization. The leader's interpretation of those values transforms them from platitudes to behaviors. For example, if a company prides itself on being people-focused, the people in the company need to see that behavior echoed by the leadership. When employees see a leader spending time with a customer or lending a hand with an employee, the rhetoric of "we're a caring company" becomes real.

Ask for the sale. Never leave 'em hanging. Ask for support. The call to action close to a presentation is a perfect example. As we said in Chapter 6, be specific about what you want your people to do. You can employ the same method when speaking one-on-one. Ask people to get behind what you want them to do. Statesmen such as Colin Powell ask for support for government initiatives. Business leaders like Jack Welch ask for an employee's commitment to a business objective. The very asking makes the person feel important, as if he or she has been singled out to do something special.

Leadership communications - in contrast to the sales cycle, which has a definite beginning, middle, and end - never really ceases. Messages may have cycles, but the communications process continues.

Play for Passion

When you were a youngster learning to write, no doubt you were instructed to write first about what you know. Leaders elevate the stakes. They are required to communicate what they know through their words and actions. But they need to do something else as well: They need to demonstrate passion - the conviction that they care. As recipients of messages throughout the day, at work, in the media, and in our daily lives, we have become very adept at discerning whether truth is coming from the speaker's platform. It has become almost reflexive for us to assume that all politicians are lying or that all businessmen are being evasive. Of course these are gross exaggerations, and unfair ones, too, but the perception remains real. So what's a leader to do?

Speak with conviction. The passion that a leader brings to the message is essential. Recall the passion that our civil rights leaders brought to their messages in the fifties and sixties. Their conviction was born of the injustice they had personally experienced. Today we see some of the same conviction in human rights workers who work on behalf of victims of hunger, war, and land mines. Their passion is genuine. As a leader, you probably feel a similar passion for what you do. Your challenge is to transfer what is inside of you to what is coming out of your mouth. If you speak simply, honestly, and straightforwardly, your conviction will ring true.

Keep in mind that you will not be feeling your best every time you speak. You may be feeling overworked, tired, or even bored. The last thing you may want to do is get up and speak about some new initiative, but remember, that's your job. You owe it to your followers, those who place their trust in you, to speak with clarity and conviction. You need to deliver the passion, even when you are feeling about as passionate as a wrung-out dishcloth. At times like this, you have to trust your instincts and use your acting abilities. Acting is not about faking conviction; it is a set of tools that you use to articulate your message in a believable manner.

Communications Theater

Communications, as has been discussed, involves far more than verbal exchanges between speaker and listener. It is also a form of theater, a pageantry of drama, history, and symbolism. It is important for leaders to keep a dramatic image in mind. We find such moments everywhere.

When the last pile of rubble was hauled from the site of Ground Zero at the World Trade Center, there was a marking of the moment. Again and again we heard that there would be no music, no speeches - just silence. It was a fitting moment of reflection to remember those who had died in the horrible and unprovoked attack.

Conventions are another form of communications theater. Whenever people united in a single purpose are gathered together, whether it is an annual convention of union members or a quadrennial presidential political convention, there are set activities that occur. Some groups open with the Pledge of Allegiance and close with a song. Political conventions are designed to peak at the selection of the presidential candidate and the candidate's address to the group and the nation. These are moments with a time-honored tradition. Consider them as part of the liturgy of the organization. They are rooted in the culture of the event. Therefore, leaders must know their meaning and abide by their significance. Here are some considerations to keep in mind.

Use symbols. Symbols are metaphors for organizational values. In our legal system, the judge wields a gavel to begin and adjourn sessions and to call for order. The gavel is a symbol of power, of coming together for a joint purpose. The range of symbols is endless. In sports, the Stanley Cup, which is given to the winner of the National Hockey League playoff series, is a potent symbol. One at a time, players and coaches skate around the rink hoisting the cup over their heads in victory, sharing the moment with the fans. The name of each player and coach is engraved on the base of the trophy. And in a spirit of genuine celebration, each member of the team gets to keep the cup for 48 hours. Traditionally players take it to their hometown and have a party so that all the player's friends and relatives can share in the moment. In recent years, the cup has traveled to Europe to the hometowns of players from Sweden, the Czech Republic, and Russia. This gesture brings the tradition of the NHL to other hockey-playing nations and demonstrates the international spirit of the game.

Dress the hall. Gatherings of people mean more when the room is "dressed" for the occasion. Create an environment that will remind people of the strengths of the organization and why they should care about it. The room may contain nothing more than a banner with a logo, or it may be dressed to the nines with pennants, banners, video walls, and product displays.

Choose your clothes carefully. Wear something that is appropriate to the expectations of the audience. Mother Teresa adapted her nun's habit to local custom. The white garment trimmed with blue served a dual purpose: It symbolized both her commitment to her religious faith and her order, the Missionaries of Charity, and her solidarity with her adopted land, India. Hamid Karzai, the leader of the post-Taliban Afghan state, uses his manner of dress to make a similar statement. He combines a Western suit with the colors, capes, and headwear of his native land.

Closer to home, a union boss addressing a group of hardhats is best off not wearing a tie, the symbol of management. Likewise, a politician who wants to curry union votes will don a jacket emblazoned with a union logo. This is not a jacket that he would wear in a corporate setting.

Likewise, the CEO who dispenses with a tie in a factory or wears cowboy boots is one who is demonstrating outwardly that he is one of the people.

Wear the hat. Hats are another form of dress. We live in the age of the baseball cap. Every leader wears one bearing the logo of the group that he or she is visiting. Hats have significance. Calvin Coolidge was photographed wearing an American Indian chief's headdress of eagle feathers. Jack Kennedy dispensed with a hat during his Inaugural Address and thereby established a trend. (Caution: Choose your hat carefully. Candidate Michael Dukakis agreed to wear an army helmet during his run for the presidency. Rather than appearing presidential, he looked ridiculous.)

Think music. Every baseball game, and for that matter every major sports event, in America begins with the National Anthem. Every Rotary Club meeting begins with a song. Music can serve two purposes: It can remind the audience of who they are as a people (the National Anthem), and it can get people up out of their seats and make them feel more energized (the Rotary Club anthem).

Consider the backdrop. Politicians are adept at creating the picture- perfect moment where the setting makes more of a statement than the words of the speaker do. For example, when Bill Clinton spoke up for the environment, he did so in a national park in the West. George W. Bush has made a strong case for schools. When he delivers a speech, he does it in a school gymnasium, drawing parallels between the immediate location and the universal values he espouses.

Respect silence. A moment of silence to reflect on the events of the day or in memory of others is a time-honored tradition. While this technique may be common among both politicians and preachers, a selective use of silence can be powerful. Leaders may use the dramatic pause to underscore their points as well as to enable people to reflect on the meaning of the words.

Communications theater is a time-honored tradition. The selection of the right background or the proper use of symbols can make the leadership message resonate more deeply than words alone can and allow it to be understood on an emotional level that rings true and helps bond the leader to her or his followers.

Theater of One

The concept of communications theater also has applicability to one-on-one communications. The leader needs to demonstrate respect for the listener in ways that go beyond words. During a formal coaching session, the leader may assume the role of host. Invite the employee into the office, offer refreshments, make certain that the person is sitting in a comfortable chair, and, if appropriate, close the door to the office. These are little things, to be sure, but they reflect courtesy for the other person, not as a performer, but as a fellow human being.

Leaders can extend these same courtesies at meetings in a variety of ways. Offer to get coffee for the group. If the meeting will run more than 60 minutes, consider treats or snack foods. Rotate the assignment of running the meeting. Do not be the first one to speak; allow others to voice their opinions first. Again, these are small measures, but when taken together they demonstrate a leader's concern for others.

Jack Welch - The Strategic Communicator

He has been called the greatest CEO in America. On one side, you have an unparalleled record of earnings growth, sustained profitability, and growth in market capitalization that stretches for more than two decades. On the other side, you have a man who can be tough as nails, brusque, and at times impatient, yet who speaks reverentially of his late mother, to whom he attributes much of his success. He is Jack Welch, chairman and CEO of General Electric from 1981 to 2001.

So much has been said and written about Welch that you would think that he invented the role of the modern CEO. He, of course, would be the first to disagree. For one thing, he would laud his predecessor, Reginald Jones, for preparing him to lead the company. More important, he would attribute his success to a couple of seemingly simple themes: focus, execution, and people. Inherent in all three is communications. And it is his relentless commitment to disseminating the message that accounts for much of his success.

Keeping It Simple

The facts of Welch's professional life are pretty straightforward. He got a Ph.D. in chemical engineering, then went to work for GE Plastics. He rose through the ranks, becoming a general manager at 33, then rising to a vice presidency and later to vice chairman of GE Credit. At age 45, he was named CEO..[1] According to Welch, his tenure at GE was focused on "three fundamental things": hardware, behavior, and work processes. By hardware, Welch means business priorities, i.e., being first or second in every market segment. Behavior refers to "boundarylessness, open idea sharing" among business units. Work processes concerns finding ways to improve the way the work gets done.[2]

These fundamentals coincide with the three phases of Welch's career in the top slot. During phase 1, he was called "Neutron Jack," getting into and out of businesses and engaging in heavy layoffs. Phase 2 was called "Work-Out"; managers worked with their people to determine strategies and tactics. Senior leaders sketched the issues and left teams to "work out" solutions; the boss could reject or accept these solutions on the spot or ask for more inform-ation - but always with a timetable. Phase 3 was Six Sigma, a quality-centric approach to business and people, or, as Welch put it, "transforming everything we do."[3]

Using Communications to Lead

Each of these phases required a "sell-in" period, and that's where Welch earned his stripes as a communicator, getting the word to GE's vast multidisciplinary business operations throughout the world. His secret? Simplicity. Welch intuitively understands how to break things down into simple parts to make them understandable by all.

Welch repeats himself purposely. "In leadership you have to exaggerate every statement you make. You've got to repeat it a thousand times. . . . Overstatements are needed to move a large organization."[4] Welch is careful to point out that you need to back up the overstatements with action. For example, when he spoke of getting rid of people who achieved but in the process trampled on other people, he meant it, and those people were systematically rooted out of the organization.[5]

An additional method for getting buy-in is to give the audience a reason to believe. Welch tells the story of the time he asked people to cut travel expenses by 30 percent. To forestall a backlash, Welch wrapped the message in the context of integrating work and life. "Look, you've [managers] been telling me your biggest problem is that you don't see your families enough. Now you're going to be seeing your families 30% more."[6] Linking the leadership message to a strategy, or, better yet, an individual benefit, helps overcome resistance. Such linkage may require some clever thinking, but as Welch showed time and again, it is essential to ensuring buy-in and uniting people for a common cause.

Welch has said that a CEO's greatest failing is "being the last to know."[7] A leader who never hears bad news is hopelessly out of touch. Welch made a point of surrounding himself with people whom he referred to as "business soul mates." These were individuals who could be counted on to give him the straight scoop on the issues. Another way Welch stayed tuned to the organization was by asking questions, sometimes for hours on end, until he learned what he needed to know.[8]

Power in People

Development of others is essential to Welch's success as CEO. Welch was an active and vigorous participant in what GE calls its Corporate Executive Council, which meets quarterly. Strategy and succession are principal themes of these meetings. At the 21/2-day sessions, senior leaders meet to "share best practices, assess the external business environment, and identify the company's most promising opportunities and most pressing problems."

Apart from getting perspective on the business, Welch used these sessions to coach and observe managers interacting with one another.[9]

During another set of meetings, known as Session C, Welch worked with senior line managers and human resource leaders to assess managerial talent. "Candor" and "execution" were the buzzwords. When Session C concluded, Welch followed up with his handwritten assessment. In keeping with Welch's claim of backing words with action, it is GE's policy to link all management development to strategic business goals. Meritocracy is what GE strives to create, and this is the thing of which Welch claims to be most proud.[10] It is no surprise, then, that many people refer to GE as the boot camp for managers, or "CEO University."[11] The ranks of American corporations are filled with GE grads, including Larry Bossidy (Allied-Signal and later Honeywell), Robert Nardelli (Home Depot), David Cote (TRW), and Jim McNerney (3M).

Some of the luster of Welch's legacy was tarnished when the perquisites that he continued to receive from GE after his retirement were revealed during divorce proceedings from his second wife. The amenities included a rent-free apartment in Manhattan, use of the corporate jet, and private security for overseas travel. The cost of these perquisites, according to Welch, amounted to less than the lump sum that GE's board had originally offered as part of his 1996 contract extension negotiations.[12]

Welch, never one to flinch from a challenge, responded with an op-ed piece in the Wall Street Journal in which he defended his compensation as well as his legacy. But not wishing to reflect negatively on the company for which he had worked so long and so hard, Welch agreed to give up his perks package and reimburse GE for expenses that had been previously covered, including the New York apartment and corporate jet service. This bill, according to Welch may be $2.5 million annually, but as he says,

[Perception] matters. And in these times when public confidence and trust have been shaken, I've learned the hard way that perception matters more than ever. . . . I don't want a great company with the highest integrity dragged into a public fight. . . . I care too much for GE and its people.[13]

Corporate Statesman

In the wake of the corporate governance scandals, Jack Welch emerged as a statesman on corporate and shareholder interests, confessing that he was as shocked as anyone by the financial foul play perpetrated by companies like Enron and Global Crossing. He traces the rise in CEOs' pay to the alignment of management compensation with shareholder value. When companies' stock soared, as happened in the nineties, senior management compensation grew at the same rate. "If you focus on pay for performance, and if you focus on results, and you focus on delivery to shareholders, you will get a system that works."[14] He admits that his total compensation for building GE's equity was generous, but he argues that it was determined fairly and honestly and for the benefit of shareholders and employees alike. He draws a distinction between the fraud perpetrated by a few and the honest earnings of the vast majority of senior leaders. Welch remains a true believer in the long-term future of his company, refusing to sell when the stock spiked, a move that "more than halved" his net worth: "I've gone up with it and I've gone down with it."[15] In his speeches, Welch reflects the same spirit of optimism about corporate America that he injected into GE "We need to have an atmosphere where CEOs are out taking risks, are out doing things positively, are out creating an atmosphere that we can win again."[16] To Welch, born into a union family and educated at a state school, it's all part of the American free enterprise system, of which he is a loyal and proud proponent.

Final Thoughts

Welch has a capacity for self-criticism. He says that his biggest mistake was not going fast enough. "I went too slow in everything I did. Yes, I was called every name in the book when I started, but if I had done in two years what took five, we would have been ahead of the curve even more."[17]

In a reflective interview with the Harvard Business Review after he had left office, Welch was even more philosophical. "My success rate was 50-50 at best. . . . That improved later because I turned out to be pretty good at it." As for strengths, Welch considers himself only "marginally" creative, but "very intuitive. I don't get fooled very often."[18]

In this same interview, Welch said that he wanted to be remembered as a people person, in contrast to earlier names like "Neutron Jack" or even "Neanderthal Jack." Why? "I like people. . . . People I work with like me."[19] Welch's affinity for others gets to the heart of his strength as a communicator. Leaders who care and respect the employees in the organization will make the time to ensure that those employees understand the message, both for the good of the enterprise and for the good of the individual, enabling him or her to give the best and get the best in return.

[1]Stuart Crainer, Business the Jack Welch Way: 10 Secrets of the Greatest Turnaround King (New York: AMACOM, 1999), pp. 3-4.

[2]Thomas J. Neff and James M. Citrin, Lessons from the Top: The Search for America's Best Business Leaders (New York: Currency/Doubleday, 1999), p. 345.

[3]Crainer, Business the Jack Welch Way, pp. 10-14.

[4]Neff and Citrin, Lessons from the Top, p. 346.

[5]Jack Welch, "Letter to Shareholders," General Electric Annual Report, 2000.

[6]Harris Collingwood and Diane Coutu, "Jack on Jack," Harvard Business Review, February 2002, pp. 91-92.

[7]Jack Welch, interview by Stuart Varney (University of Michigan Business School), CEO Exchange, PBS, 2001.

[8]Collingwood and Coutu, "Jack on Jack," pp. 92-93.

[9]Ram Charan, "GE's Secret Weapon," sidebar in "Conquering a Culture of Indecision," Harvard Business Review, April 2001, p. 81.

[10]Varney interview.

[12]Leslie Wayne and Alex Kuczynski, "Jack Welch in Unlikely Company," New York Times, Sept. 16, 2002.

[13]Jack Welch, "Commentary: My Dilemma - And How I Resolved It," Wall Street Journal, Sept. 16, 2002.

[14]Paul Solman, "Executive Excess: Part 4," NewsHour with Jim Lehrer, PBS, Dec. 5, 2002.

[15]Ibid.

[16]Ibid.

[17]Neff and Citrin, Lessons from the Top, p. 346.

[18]Collingwood and Coutu, "Jack on Jack," pp. 92, 94.

[19]Ibid., p. 94.