Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California - Westside Toastmasters on Meetup

Alignment of Personal and Corporate Goals

Coaching can be an effective means of aligning individual aspirations with organizational goals. It is the coach's responsibility to bring out the talent within the individual and to ensure that there is a good match between that talent and the organization's needs. For example, an accountant wants to work in a place where she or he can use her or his analytical skills and make a contribution to corporate objectives. The company needs good accountants to manage its finances in order to achieve its fiscal goals. In this situation, the goals of the employee and the company are aligned. Sometimes such alignment of goals may not be possible. If, for example, an employee prefers working solo rather than as a part of a team, an organization where team culture rules may not be a good fit. The coach can advise the individual that he or she might be happier working somewhere else, in a more autonomous environment. And this can be good news. A number of successful entrepreneurs have left the shelter of large organizations because they craved the independence of running their own business. And some will admit that they based their decision to leave on the advice of well-intentioned coaches.

| Note |

When addressing the role that coaches play in organizational alignment, I prefer to focus on organizational goals rather than organizational values. Goal refers to objectives—what the organization wants to achieve. You can draw a direct parallel between organizational goals and individual performance objectives—what an individual needs to achieve. Values refers to what an organization stands for and believes in; the same applies to individuals. And while an employee should reflect the corporate values, such as integrity, honesty, and ethics, these are central to the individual's character and typically are not what coaches focus on. I do not think you can coach a person into a value system, e.g., a dishonest person cannot be coached into honesty. It is more authentic and powerful to have a coach's behavior reflect the corporate value system. However, an individual can be coached to achieve performance objectives that are in alignment with organizational goals.[2] |

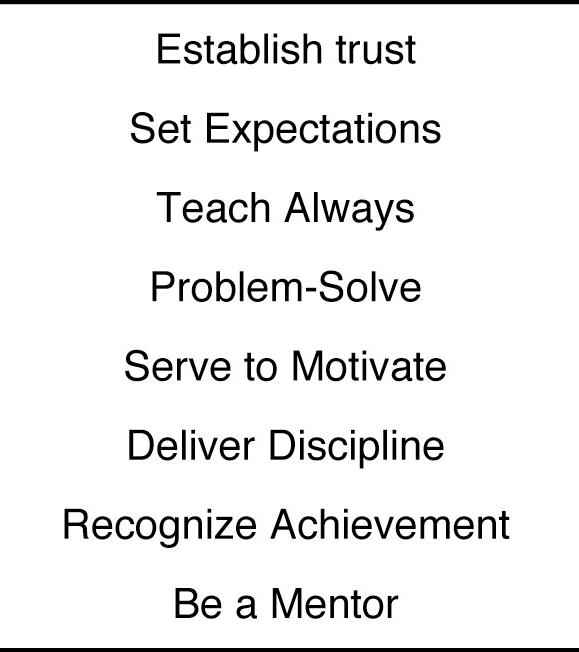

Here are eight ways to begin to develop a strong coaching technique (see Figure 10-1).

Establish Trust

Trust is at the core of every coaching relationship. To build a sense of trust, a leader-coach must communicate that he or she has the individual's best interest at heart, and that whatever he or she says or does is done with the individual's best interest in mind. Once the coach and the recipient understand each other, they can create a relationship of mutual benefit. The coach helps the individual achieve personal goals, and the individual helps the coach realize organizational goals. Harvey Penick, throughout his seven decades of coaching championship golfers, founded his relationships on trust; players understood that Penick wanted them to excel, and so they should listen to his counsel. At the same time, Penick did not mold players to a specific swing pattern; he worked within the physical capabilities of each player. This approach depends fundamentally upon respect for a player's talent and engenders trust.

Few things earn the respect of a team more than a coach's willingness to accept criticism in public. In sports, good coaches never publicly blame the players or their assistants for a defeat. They take the criticism. Behind closed doors, within the confines of "family," a coach will rip into players who need ripping into, just as he or she will praise those who are deserving of praise. Corporate leader-coaches can do the same. They should stand up for their people in front of senior management and do whatever is possible to provide their employees with the support and the resources they need if they are to perform. Advocating on behalf of employees is a sure way to gain employees' respect. But a coach must be skillful about this; he or she cannot alienate the management team. Coaches, too, need to maintain the trust of the bosses.

Set Expectations

The individual needs to know what is expected of her or him, and it is up to the coach to be specific about what is needed. As an extension of the goals alignment, the leader-coach needs to make certain that the department is aligned with the organizational goals. Furthermore, the coach needs to ensure that the individuals on the team know what they are supposed to do. Many managers ask their direct reports to set their own performance objectives. This practice is a good one, but the manager owes it to both the team and the individuals to contribute to those objectives. A simple sign-off is not good enough; the manager owes the employee a conversation about it.

As part of the conversation on performance, the leader-coach must get the individual's buy-in. And it is here that the manager must be very clear and specific. Make certain that goals and objectives are in writing, and gain agreement on what the individual will do by when. Timeliness and deadlines are essential. If this is not made clear, the employee may legitimately state that he or she will do it when he or she gets around to it. The deadlines add a sense of urgency and lead naturally to the manager's following up and following through. In the wake of the Super Bowl, Tom Brady, as quarterback of his team, set expectations for himself that he wanted to repeat, and as team leader he thereby established expectations for everyone. Brady backed those expectations with a commitment to off-season training.

Teach Always

Teaching is fundamental to coaching; providing information and ensuring that learning occurs is what coaches do. Vince Lombardi, who began his career in coaching as a high school teacher of math and sciences, was first and foremost a teacher. With a piece of chalk and a blackboard, he could talk for hours to players or to fellow coaches at clinics about the Xs and Os of football. Dressed in a sweatshirt and a baseball cap and with a whistle around his neck, Lombardi was the archetypal image of a football coach of his era. Coaching instruction can take many forms. It may be explicit: Pointers on how to operate a piece of machinery, or tips on how to structure a report. Or the instruction may be implicit, such as a parable or a story that the coach relates. What is important is that the coach relates the instruction in ways that the individual can accept and understand.

For this reason, coaches must be active listeners, attentive to communication clues. Blank stares or bored looks indicate that the lesson has no meaning. Conversely, head nods and questions mean that the lesson may be getting through. The coach must work to find methods to engage the employee's interest and hold it so that learning does occur.

It is no coincidence that many coaches are good storytellers. Stories offer the opportunity to impart important life lessons in a manner that is accessible and even enjoyable rather than condescending and preachy. For this reason, coaches keep a personal inventory of stories intended to evoke the appropriate emotion for the situation—admiration, inspiration, tears, or laughter. Importantly, all of these stories contain a pithy message wrapped neatly inside. (See Chapter 12)

Problem-Solve

Coaches must possess a sixth sense about individual performance as well as team performance. In basketball, when one team begins a scoring run, the opposing coach will often call a time-out. He will pull the team together (physically and mentally) to focus its energies on the task at hand. He will point out both what the team is doing wrong and what it is capable of doing. Great coaches can turn around team performance in a matter of minutes. In business, good coaches have similar abilities. They can rally a team around a goal and provide direction. When the team encounters an obstacle, the coach finds ways to overcome or avoid the problem. Specifically, good coaches go around to each team member and ask what type of help that team member needs: time, resources, or staff. Coaches then affirm the individual's value to the project and provide ongoing encouragement. Jack Welch, a Ph.D. chemist turned manager, learned early that a successful career in management depended upon an ability to solve problems. He continued to preach that throughout his career.

Similarly, if there are personality conflicts, it is up to the coach to intervene. Often the coach cannot impose a solution, other than forced separation, but he or she can try to get to the root of the problem and discover ways for the individuals who are at loggerheads to work together. Ideally, a solution will come from the two parties themselves, but it will be the coach who brings them together and gets them talking.

And keep in mind that coaches do not wait for problems to occur. As leaders who exemplify the "management by walking around" philosophy, they have their antennae tuned to the rhythm of the team. They are responsible not simply for maintaining morale, but for invigorating it. When coaches sense that something is amiss, they seek out the cause immediately. Likewise, when a crisis occurs, they do not hesitate to intervene. Good coaches drop everything and move to solve the problem immediately. Quick action has three benefits: It can provide immediate relief and ameliorate the situation, it can prevent a small problem from growing larger, and it demonstrates to the organization that the coach has people's best interests at heart.

Serve to Motivate

Good coaches are known as masters of motivation; they prod their teams to win. Motivation, of course, cannot be imposed upon an individual; it stems from the person's inner drive to achieve. What coaches can do is establish an environment in which individuals can thrive. They can, as mentioned earlier, provide alignment between the goals of the individual and the goals of the organization. At the same time, good motivators need to know when to push and when to hold back. Some individuals need someone prodding them all the time; others prefer a laid-back, hands-off approach. It is the coach who designs a system, or an approach, that is tailored to bring out the best in the individual for the good of everyone. Part of that system includes a healthy dose of recognition for a job well done. Joe Torre of the Yankees is a coach who knows how to do all three—prod the player who may be slacking, encourage the player who is struggling, and frequently recognize everyone who is doing a good job.

Deliver Discipline

Not everyone responds to advice. Metaphorically speaking, sometimes the stick can be more effective than the carrot. Discipline connotes compliance with the rules, be they rules of quality control or rules of conduct. Delivering discipline, therefore, is another form of maintaining standards and ensuring that behavior has consequences. We see this often in the world of sports. A coach will bench a star player because the player is not practicing hard enough, or because the player is not demonstrating commitment to the team. In the workplace, a leader-coach can call aside an employee who is not pulling his or her weight, e.g., not sharing information with other employees, showing up late for meetings, or regularly leaving work early. The coach can warn the employee that if the deficient behavior does not improve, the employee will suffer the consequences: restriction of perks, forfeit of bonus pay, or the loss of a promotion.

Discipline will be effective, however, only when it is backed by trust. Every coach must focus on behavior (what the person does) rather than personality (what the person is) and must communicate that any punishment is due to deficient behavior. Vince Lombardi was famous for having a star player or two whom he could publicly excoriate. Sometimes this was deserved; other times it was an act to get the team's attention. Lombardi did not want to play favorites, and when he purposely went after a star player, everyone else would fall into line.

Discipline need not always connote punishment. Discipline can take the form of adhering to a value system, even in the face of adversity. Coaches teach discipline not so much by their words as by their example. When employees see a coach making a tough decision, particularly one that involves personal inconvenience, they learn to respect that coach. Effective discipline ultimately leads to self-discipline, with employees taking responsibility for themselves and their actions. When this occurs, the coach has done the job.

[2]Harley-Davidson shifted the discussion from values to behaviors. While people can debate values, what often matters more is behaviors, how people interact with others. Behaviors are observable and can be coached. For more insights into the issue of corporate values, refer to Rich Teerlink and Lee Ozley, More than a Motorcycle: The Leadership Journey at Harley-Davidson, pp. 153-157.