Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 1: Defining The Undefinable

Overview

That's a joke, right? People talk a lot about 'creativity,' but what exactly does that mean? The dictionary gives a straightforward definition: the ability to be original, to imagine new things and new ideas.

Businesses thirst for new ideas and always claim to be on the lookout for creative solutions to problems - you don't see anyone using the tagline 'We Do Things the Old, Boring Way.' Creativity in today's business world means coming up with ideas that make money, win business, and make the competition shake in its boots - ideas that have equal measures of uniqueness and relevance. The problem is that most good businesspeople are trained to be analysts: Analyze the consumer demographics, analyze your sales data, analyze the performance of your competitors. Obviously, there is great value in being smart about your business - in knowing to whom you're selling and how much they're buying.

However, analysis can only set the stage for innovation. A creative solution can't be analyzed into existence. Brilliant ideas seem obvious only after the fact - once someone has a great idea, then all the analysts can tell you exactly why it's a great idea. But the process doesn't work backwards; all the data in the world can't spontaneously produce a new idea.

To be creative is to reach out into the unknown, to imagine something that doesn't currently exist. That implies risk, and if you're a good businessperson, you're rightly suspicious of risk. Organizations thrive on numbers, on proof, on hard facts. New ideas are simultaneously desired and feared. We all want them-but where are they? How do we uncover them? Why do some businesses seem to be innovation machines? It's easy to see a good idea once it already exists, and it's easier in hindsight to see an opportunity once it's already been exploited. What's hard is developing a process that identifies opportunities and generates ideas on a consistent basis. That's what this resource is dedicated to providing for you.

You could define insanity as 'doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result.' Everywhere I looked, I saw companies doing just that: trying something that was successful in the past and expecting to get something new out of the process.

Exercise

Where Do You Get Your Ideas?

Despite the provocative question on the previous page, this exercise is not really going to tell you if you're insane. (The most I can help you there is to repeat what a friend once told me: 'If you think you are, you probably aren't.' Or was that the other way around!) But this will help illustrate your style of approaching new problems.

Imagine you've been hired to create a new brand of tennis shoe and given absolute freedom to do anything you want. Right now, before you read any further, use the space on this page to roughly sketch its appearance and list its features.

Left Brain, Right Brain

If you're interested in creativity, then you've probably been exposed to the concept of 'left-brain' and 'right-brain' thinking.

The theory grew out of the work of Nobel Prize-winning psychobiologist Roger Sperry, whose study of epileptic patients showed that each hemisphere of the brain processed different types of information. Broadly put, the left brain is the objective, analytical, logical half of the brain, looking at information sequentially and focusing on individual parts rather than on the whole (remember left = logical). The right brain, on the other hand, is the subjective, intuitive, playful part of the brain; it looks at information in a more random fashion, seeing the whole rather than the parts.

The 'voilà!' moments of innovation come from the right brain: You suddenly see how unrelated things connect; you see a new solution to a problem; you are struck by a new idea from out of nowhere. Monumental discoveries from penicillin to nylon to X rays were all made by accident-through the serendipitous flashes of insight that come from the right hemisphere.

But once you have that insight, what do you do with it? Here's where the left brain comes into play, giving concrete form and shape to the right-brain-inspired concepts.

If you're reading this resource, it's a good bet that you are more comfortable operating in your left brain than in your right brain. The exercises throughout the book are designed to get your right brain activated: Rather than sit and wait for 'inspiration' to strike, you can prime the pump and get the ideas flowing. Once you have the raw material (concepts and ideas), you can let the left brain do its thing and start editing and planning.

It's important for you to remember that you can't simultaneously be in 'idea-generation mode' and in 'editing / analyzing mode.' One has to follow the other.

What this means is that when you're doing the various exercises in this resource, you will be sorely tempted to analyze the experience as you are going through it. 'Am I doing it right? Is this what's supposed to be happening? How do I know if it's working?'

In order to access your right brain with any success, you have to do your utmost to keep your analytical brain from kicking in until after you're done with the exercise.

There are explanations of why and how the exercises function and the kinds of results they can have (to satisfy the logical cravings of the left brain). But in the end, they are all trying to accomplish the same thing: to stimulate the right brain, the source of inspiration.

Exercise

A Mental Picture Of Your Brain

Close your eyes and summon up a visual image of the right side of your brain.

Then do the same for the left side.

Quickly sketch the image that you see. Go with the first thing that comes to mind. Don't overthink.

When I first did this exercise, I saw my right brain as a mountainside meadow filled with wildflowers and people dancing and singing.

I saw my left brain as walls lined with steel shelves. There was a steel trap on one of them, but it was covered with dust.

Nowadays, my left brain is neater and cleaner . . . but the first image is telling, isn't it?

Exercise

Soliloquy

A soliloquy is a monologue in which someone gives voice to his or her deep feelings. Shakespeare used this device a lot in his plays: one of the most famous begins, 'To be or not to be. . . .' In this exercise, continuing the process of getting in touch with your existing beliefs about creativity, you're going to give voice to the right side of your brain, the part associated with creativity and intuition.

Fill in the following blanks as you believe your right brain would. Have fun, lighten up, and write down whatever comes to you. Don't censor yourself.

I am the spirit of ------------------

I have traveled -------------------

I have met --------------------

I have conquered ------------------

I have learned -------------------

I have tried and failed ---------------

I am stuck on -------------------

I yearn for --------------------

Logic Versus Energy

We all know a good idea when we see it. A good idea grips you. There's an immediate gut reaction, a zing that makes you feel inside like, 'Yes, of course! That's right. That's cool. I want that.'

A zingy idea gets your attention. Ideas like that have voltage, energy, life. They have the energy to make you different. They have the power to change your mind, your imagination, even your actions. They have the oomph to change your company or your industry.

A good idea is relevant to your life. It resonates with you . . . and yet it's different enough that it didn't occur to you before. No matter what the idea or innovation, if it's great enough to change you, it has that magic combination of relevance and difference.

I've sat through too many meetings where the people in charge approved the idea that made sense rather than the idea that got a reaction from the room. In meeting rooms all over America right now, managers are arguing for the 'make sense' ideas rather than the ideas with a spark of energy. In fact, the truth is that the worst idea is the one that makes sense. If you're not excited and energized by your idea, what consumer is going to be?

This is another instance of the left brain (logic) triumphing over the right brain (intuition). The majority of us live in our left brain. We've been trained to be logical people. Obviously, there's value in logic - at the right time. When it comes to innovation, the role of logic is to sort and strategize rather than to generate. Ideas that don't elicit a reaction in a meeting room are unlikely to generate a reaction in the marketplace.

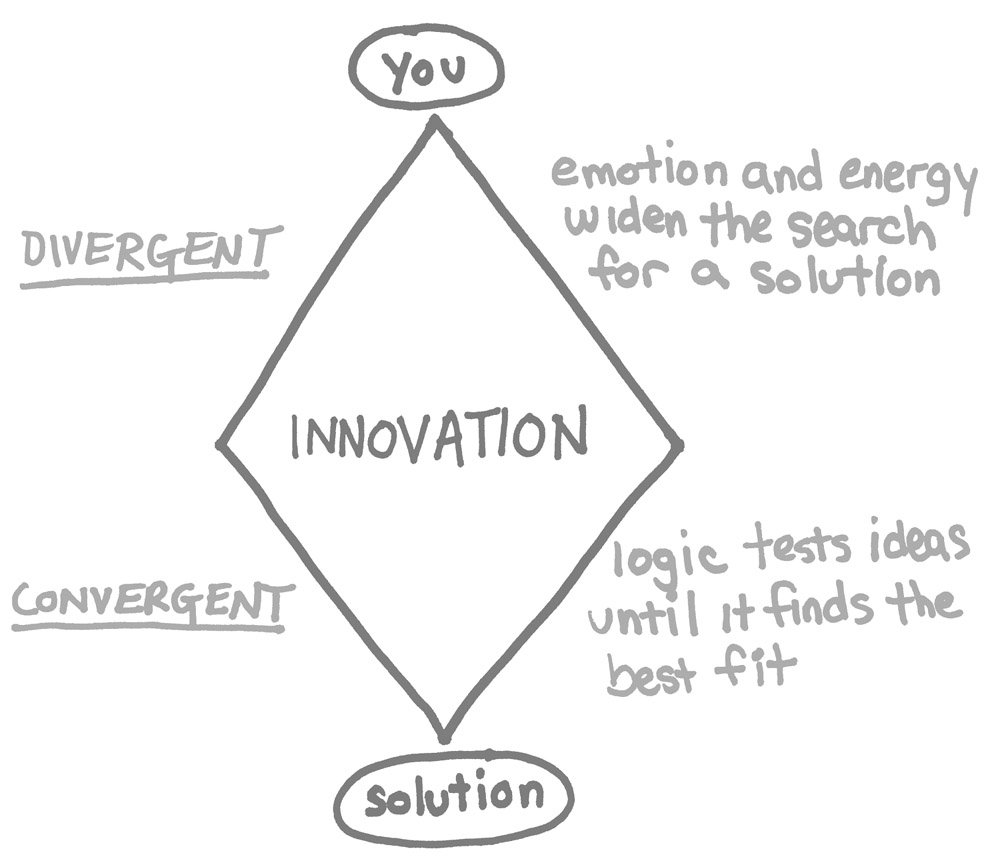

Reason has a role in the innovation process; it's just not operative at the beginning. John Kao and Dorothy Leonard at Harvard Business School teach that the process of innovation can be thought of as a diamond shape: It has a divergent and a convergent side.

The divergent top of the process is driven by emotion and energy (right-brain qualities); the convergent part of the process is driven more by logic, as the left brain comes back into play. Many of my clients are much more comfortable in the convergent part of the process than in the divergent part. The divergent part can feel uncomfortable, and that's OK. Just stay there for an hour or a day longer than you're used to, and you may be amazed at what creative genius steps forward. We need to let our logical minds take a rest on the hammock for a little while we're working early on (just as I've asked you to do with the exercises in this resource).

When we let go of logic for a moment, we can be open to ideas that might not 'make sense,' but that get a reaction. We've all been in meetings where people react strongly to something - perhaps with a laugh, an inadvertent 'mmm . . . ,' scorn, anger, the hair on the back of the neck going up. Usually those ideas are the ones that get discarded and discounted.

Those are the ideas with energy. They've elicited a reaction. Some nugget in that comment may have the potential to elicit a reaction in the marketplace as well.

Do you always want to run with the raw 'mmm . . . ' idea? Of course not. This is where our logical minds help us out. We can take the basic, unfiltered ideas that emerge during the divergent phase of thinking and use our logical minds to shape them and mold them.

Energy is important. You can find energy by looking for paradox, conflict, and friction. When you find those 'hot spots,' you know that you've found a source of energy. That's fertile territory in which to start drilling, exploring, and generating ideas.

All of the innovations that have had the power to change my life have in some way given me a fresh way to resolve a paradox I'd been living with. For example, when I was a single parent I wanted to hire other people to do as much stuff for me as possible. Who has the time or the energy for an expedition to the grocery store multiple times per week? Yet my kids are picky, and I too am fussy. I want it done my way.

Then Peapod introduced an online grocery shopping and delivery service that was personalized to my needs. I could order all my groceries - and specify that I wanted bananas that were really ripe - and the next day they were delivered to my third-floor walk-up condo. Everything was just the way I wanted it, yet I didn't have to do it myself. Peapod is a great resolution of conflicting desires.

We'll use various examples throughout this resource, but we don't necessarily believe in studying case histories in minute detail. That path leads to my fledgling 'this is the way everyone else has done it' floor wax presentation. Everywhere in our culture - in the marketplace, on television, in the movies - you can see examples of imitation substituting for innovation. Carefully putting your feet into someone else's footsteps is not the same as learning how to walk.

Instead, we're going to look beneath the surface, at the process of thinking creatively - and at the ways in which we often stop ourselves from thinking this way.

This resource will help you have ideas that work because they grip people. The opportunities for having ideas that work are all around us every day. They come out of the stuff of life; they don't come from mad scientists with test tubes shut up in labs all day long. We all have situations that we accept with a shrug and a feeling that 'that's just the way life is.' These are the situations in which we can choose to complain or to create. They are fertile territory for powerful ideas.