Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 2: Enemies Of Ideas and Innovation

Overview

If we were all fully capable of inventing novel solutions to every challenge we faced, all of our problems would be solved quickly. What I've found is that we're all held back to some degree by enemies of ideas. In this chapter, we will explore some simple ways to stop these enemies in their tracks before they shut us down completely.

'Of course,' you say to yourself, 'I have good ideas. I'm a creative problem solver. I'm open-minded. I'm not like those cartoon middle managers who hide in cubicles and squash any new ideas that cross their desks. No, I want to break boundaries, push the envelope.

'But...

Everybody wants to be innovative. Nobody wants to be known as the guy who said that the lightbulb was a bad idea that would never work. The tricky thing about the enemies of ideas, though, is that you can't always recognize them.

It's ironic that many patterns of behavior and modes of thinking that work well in performing certain structured activities (test taking, for example) only get in the way when we try to use them to come up with new ideas. We're taught from an early age to know the right answer, to be polite, to be sensible, to stick with the tried and true, to try harder. It's not so easy to abandon the behaviors that we know to be 'right.'

The tools and techniques that many companies employ provide an exquisitely sophisticated snapshot of what is; however, those same tools and techniques simply don't work to show what could be. Many companies rely on expensive and exquisitely detailed reports that show every nuance of brand sales, product usage, brand-switching behavior, cost sensitivity, and so on. What these reports don't show is how the power of an idea could change things.

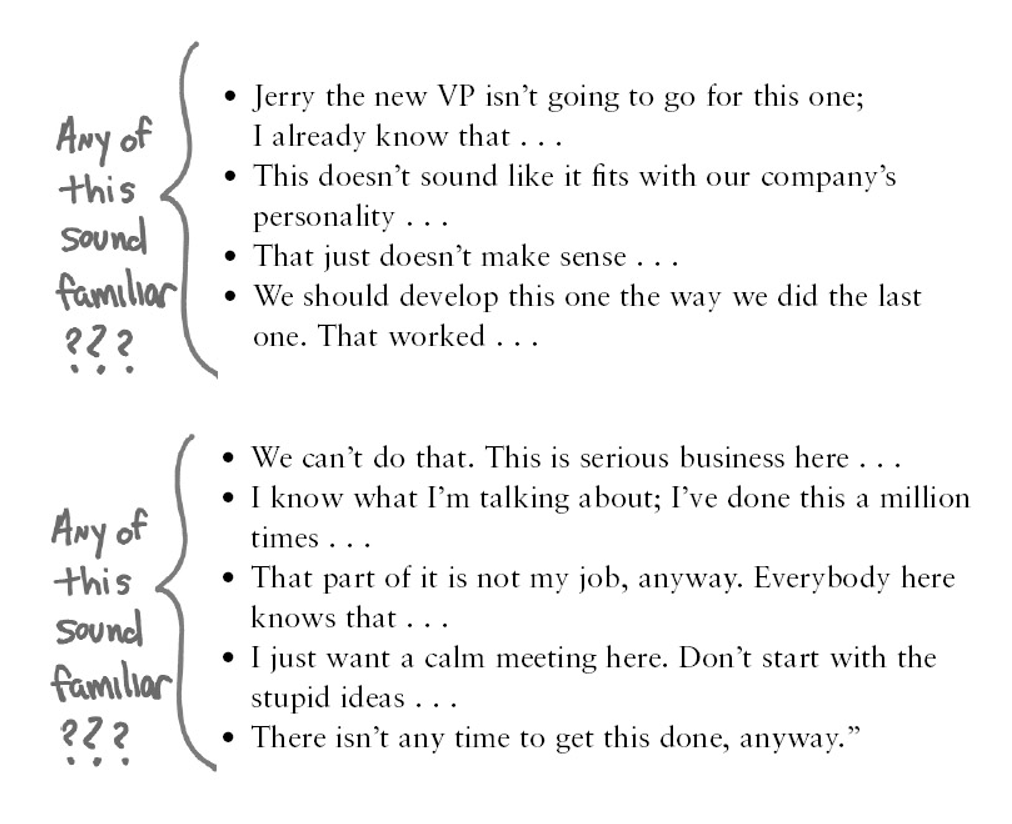

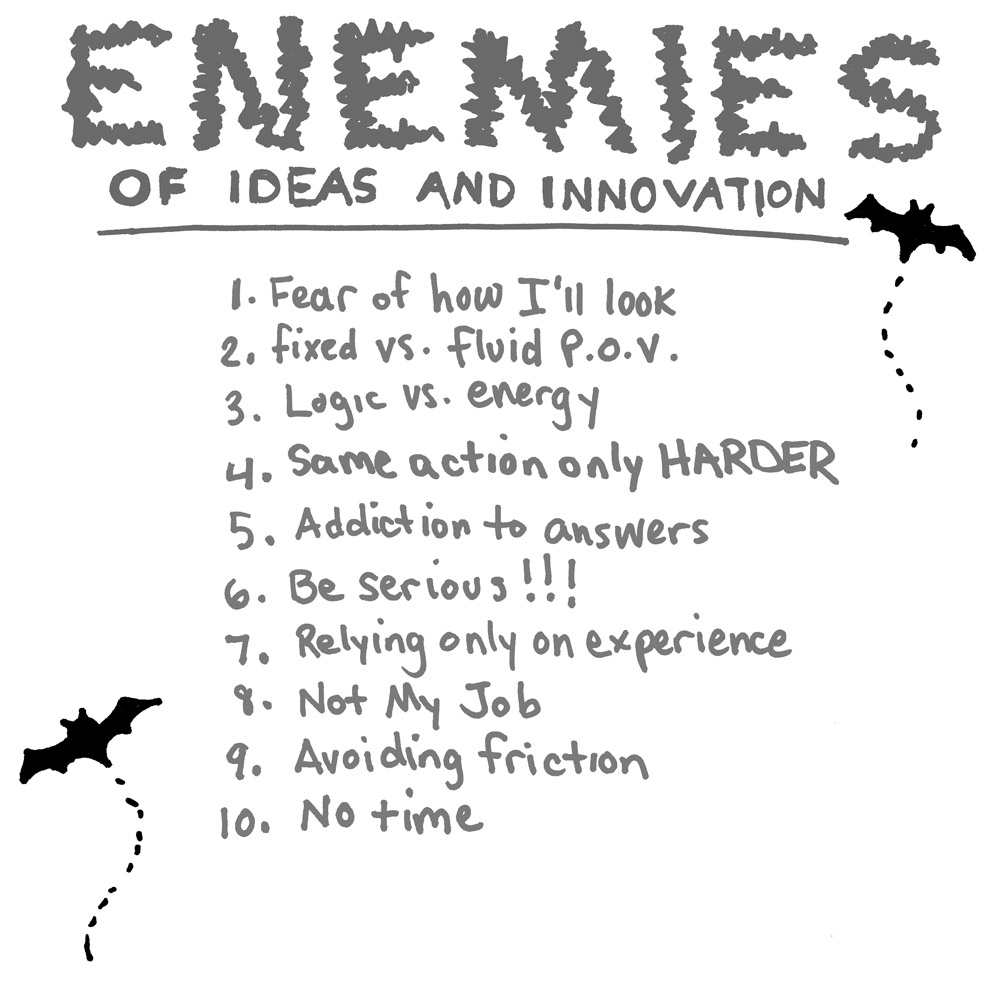

In my work, I've encountered the same enemies of ideas over and over. Some of them turn up everywhere, while others seem more specific to particular organizations. In the pages that follow, we'll look at the ten most prevalent enemies of ideas that I've experienced.

The first step to eliminating these barriers is to recognize them. Which ones are most present in your work? In your life?

This is a big one, but it's a hard one to admit to. No one is willing to own up to being afraid. Cautious, prudent, perhaps even conservative, but not afraid. In the corporate world, admitting fear is tantamount to admitting failure. It's just not done.

But the fear is there, even if it's well disguised. We all remember only too well the feeling of being in front of the class and making some kind of mistake. Your face reddens; your adrenaline starts pumping; you feel sweat trickling down the back of your neck. It's not an experience that anyone wants to repeat.

We go through elementary school, high school, college, graduate school, and up through the ranks of companies, always with an authority figure that we have to please. Even CEOs have to answer to Wall Street. And underneath our well-coordinated businesswear, somewhere there's a fourth grader who has resolved never to look stupid in class again.

Maybe you don't call it fear; how about anxiety? Apprehension? Stress? Worry? When you don't feel secure in a situation, you won't allow yourself to risk. You can imagine pitching a new idea to your colleagues, clients, or supervisors and getting the eye roll, the puzzled look, the dismissive comment ('interesting, but not what we're going for here').

Fear is paralyzing. The fear of being judged, of looking stupid, of being wrong, of failing, of taking the blame-it's lurking just beneath the surface, in the clever disguise of caution. When you can't put the full force of your enthusiasm and passion behind a new idea, that idea will be dead on arrival.

One thing I've learned is that whatever I focus on grows. So if I focus on the anxiety that gnaws in my belly, it gets so big that it's paralyzing. On the other hand, if I focus on what my next appropriate action should be, it gets me into motion.

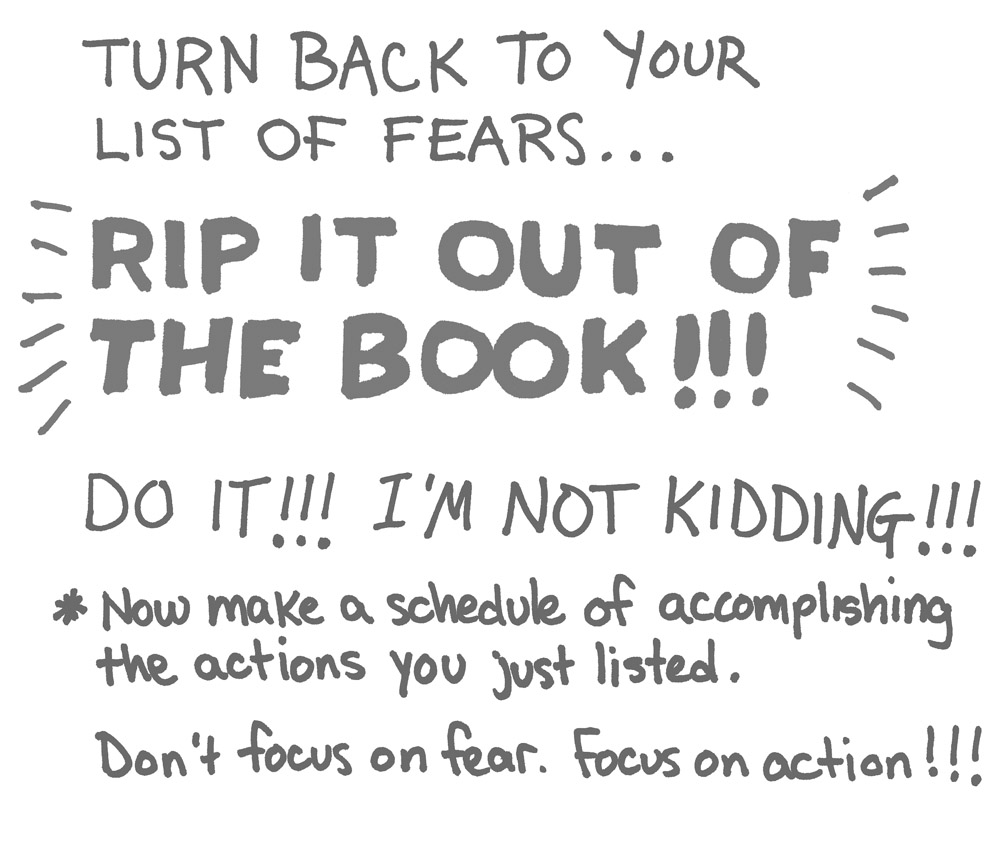

Exercise

What Are You Afraid Of?

This is a very important exercise. Cover this page with a list of what you're afraid of. Rational, irrational, it doesn't matter. This is the place to let your fears loose. Get them all out. Use the back of the page. Study each one carefully, because it may lead you to others.

Exercise

What Would You Do?

On this page, make a list of all the actions you would take if you didn't have the fears you just listed. What would you do if you could set aside those fears for a moment? If I told you to borrow my faith that it will all work out, what action could you take today?

All of us, especially those of us who are ambitious and driven, are used to advancing our own point of view. We have a particular way of seeing things, and the more focused and specific that vision is, the more successful we are.

This kind of mindset can work brilliantly in a debate, but it doesn't serve you as well when you're trying to see fresh solutions to issues or opportunities. From any one perspective, you can see only 180 degrees of the world. What you need is to see the full 360.

It's easy to forget that there are many people involved in any business transaction, all of whom have different needs and opinions. If you can shift your point of view and get inside the skin of someone else-your consumer, your supplier, the guy from R&D - you'll be able to dramatically expand the number of possibilities that you can see.

There is the hidden fallacy that if you can somehow push your own particular point of view, amplify it, and make it loud enough, everyone will fall into line. If you consider any monopoly (The Ford Motor Company back in the day of the Model T, for instance), you'll find this mode of thinking: You can have a car in any color, as long as it's black. A one-size-fits-all approach dismisses the validity of any alternative opinions.

This may seem obvious when you think about extremes (for example, a dictatorship versus an open society), but it can be hard to spot in yourself. When you're thinking about a particular problem, really peel away the assumptions you're making. 'We don't need to make cars in different colors. Nobody cares what the car looks like - it's a utilitarian appliance. All people want is to get from one place to the other.'

Closely related to this way of thinking is, 'We've always done it this way' (see Enemy Seven). Sometimes you need to ask yourself, 'If I were going into business to compete with my own company, where would I start? Whose needs are we not serving? Why do people prefer this feature in my category? Why is that important to them? How does it fit into the rest of their lives?'

The Wright brothers, inventors of the first successful heavier-than-air craft, took nothing at face value. Every inventor who was working on building an airplane at that time was relying on the same tables of aeronautical data that had been compiled by an earlier pioneer in the field. The Wrights challenged conventional thinking and began from scratch, questioning every assumption that their predecessors had made.

When they were trying to solve a problem, the brothers would each take one side and fiercely debate the issue, then they would change sides and argue the opposite viewpoint just as vigorously. They tested every theory this way, ensuring that they saw every issue from every angle.

To a conventional thinker, it may seem that conceding the existence of opposing views will weaken your own convictions. Paradoxically, the ability to see many sides of a situation allows you to come up with the most viable solutions. Adopt a diplomat's mindset: What is the person on the opposite side of the table thinking? What can you learn from that person?

Exercise

Get To Know Someone

A friend asks her clients to write a list of everything they know about the person they're communicating with, including a list of the things that they can appreciate about that person. After all, the person is someone's child, brother, friend. Think about someone in your company, about your competition, about your customers.

What's their background? What's their history?

What's important to them? Why are they at this meeting?

What motivates them?

What's missing for them?

What are their hopes and fears?

Most of us write down the logical things that are said in meetings: 'That seems like the sensible course of action.' There are always ideas that seem perfectly rational, seem to solve the problem at hand, and yet have no 'spark' in them. They are the equivalent of middle-of-the-road political candidates: They satisfy all the basic requirements, but they won't get anyone up out of their chair to go to the polls.

How many times have you seen a movie (or even a 'coming attractions' trailer for a movie) and realized that you know exactly how everything will turn out? A leads to B leads to C . . . all the necessary plot points are covered (car chase! love scene! heart-tugging ending!), and the movie unspools in a completely predictable fashion. Everything makes sense, but nothing is exciting. The best moments come when something unexpected enters the story - not something completely random, but a twist, a jolt that pushes the action out of the predictable.

In a meeting, the 'logical' idea is often one that can be completely understood immediately. You know how everything will turn out. There are no surprises. The idea with energy behind it is often a surprise-and it gets a reaction.

You can see how listening for logic easily goes hand-in-hand with the first enemy of innovation, giving in to fear. If you're looking for no risk, then every idea should be rational, by-the-numbers, and completely unsurprising. If you're only listening for logic, then any idea that's new can immediately be picked apart and found to be unworkable (many times, we'll do this in our heads before a new idea has a chance to make it out into the room).

When you're listening for energy, write down the thing that makes the room react. What makes people laugh? Groan? Get angry?

Write down all the ideas with colored pencils, markers, or crayons. Tepid ideas get tepid colors; energetic ideas get written down in big, bold letters. Draw circles around them; decorate them with stars; follow them with exclamation points! The ideas that make a stir in the meeting room have a nugget of energy that will get a reaction from your customers as well.

The secret of listening for energy is having the patience to figure out how to make the energetic ideas doable. It requires being able to engage in 'what-ifs' without dismissing anything as impossible.

Hold on to those ideas that spark a reaction, even if it's not immediately clear how they can be put into practice. How can we expect to get a reaction from the marketplace when we can't get a reaction from our team?

This brings us back to the idea of left-brain-right-brain cooperation. Use the right brain to make the 'leaps of logic' that generate ideas, and use the left brain to find a way to make those ideas work. One side supplies the raw material; the other side edits, shapes, and polishes. Just don't try to make the left brain do the right brain's work. Let energy come first, then use logic.

Exercise

Keeping Track Of The Energy

When you go to your next meeting, bring a box of colored pencils. Every time somebody says something that gets a reaction in the room, write it down in color.

At the end of the meeting, go back and see how you can work with those ideas to make them doable.

This may be true when you're working with a hammer and nails, but it isn't true in meetings. The moments when people make breakthroughs - when the right idea just pops into someone's mind - often come when they're relaxing after a period of intense concentration.

If you ask most people when breakthrough ideas have come to them, you'll find that they've been driving, or in the shower, or walking-performing a simple task that keeps part of their brain occupied but frees the 'back part' of their brain to rummage around and dig up new ideas.

So, don't fall into the trap of hammering away at a problem for too long. Make it a regular practice to schedule in 15-minute breaks after you've been working for, say, two or three hours. Outlaw any business talk during the break. Step outside for a breath of fresh air or a walk around the block.

Bring in a yoga instructor who can show you a few asanas that you can do easily in your work clothes.

Sometimes you need to change the texture of your normal work session to get new and better results. Try changing the players involved - besides the usual team members, invite an unusual expert to participate (for instance, an author, a student, or an authority with a differing point of view). The group dynamic will always shift when there is a new presence in the room. Break from whatever your usual meeting procedure is - disrupt the usual patterns. Play word association games; solve puzzles together; put Legos on the table.

Really look at your work environment-chances are it's a completely left-brain-focused space. Conference rooms with straight lines, inconspicuous overhead lighting, colors that don't assert themselves - these are all fine for logical, straight- ahead thinking, but not so conducive to thinking in new ways.

Break away from the usual. Hold your meeting in a different physical environment - a theater stage, a funky loft, or a rec center.

This enemy also shows up as 'the same information, only louder, will get different results.' Ad agencies make this argument to their clients all the time: 'The campaign would work if you put more money behind it.' And sometimes that's true. Other times you've got to change what you're saying, how you're saying it, or where you're saying it in order to get through to someone in a new way. I've also had bosses who seemed to believe that the louder they said the same thing, the better the results they'd get. Not true.

Again, remember that the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.

Exercise

Take A Break!

Set the book down. Your crucial assignment is to . . .

Draw a picture.

Go for a walk for 15 minutes.

Do some stretches.

Listen to some music you enjoy.

See what new ideas pop into your consciousness while you're gone. Write them down and share them with your team.

Most businesspeople know lots of answers. We all got good scores on our SATs. We knew the answer to 'where do you want to be in five years?' when we were interviewing for jobs. We know the latest P&L projections. The problem is that needing to always know the answers doesn't allow us to wonder about the questions.

Think about the standard interview questions for a moment. Chances are you've been on one or both sides of this interaction. Have you ever wondered, why are these the questions? Has anyone ever given a fresh, inspired, unrehearsed answer to the question, 'Where do you want to be in five years?'

This addiction to answers is a natural response to the way we're taught. You come into a situation (a classroom) in which the same process happens day in and day out: You are presented with a question, and you are expected to produce the answer, an answer that someone else already knows (in fact, chances are it's an answer that everyone else in the class also knows). The answer is on the teacher's copy of the test or hiding in the back of the book. Your entire scholastic career is built up of numbers - percentages that reflect how many questions you answered correctly.

Linear thinking and problem solving are good skills to have, but they sometimes act as blinders. We obediently search for answers to the questions, but it doesn't occur to us to wonder about the larger picture. When you're asked in second grade about how many apples Johnny has if he starts with five and gives two away, all you are expected to say is, 'Three.' You aren't asked to think about who Johnny is, why he has so many apples, whom he's giving them to, or why this simple math question is framed as a story about an imaginary kid with pretend apples.

You can see a pattern developing with all the enemies of innovation: relying on unthreatening logic, accepting boundaries without question, not wanting to risk challenging the status quo. Everything leads to the celebration of the obvious and the dull.

We have to shake ourselves loose from the deep inner conviction that, somewhere, there is a Big Book of Answers that holds the solution to every problem. If this resource were a book of answers, there would simply be a list of case studies with their corresponding solutions - but all that does is deliver the end result without examining the process that brought the result about. There is no flipping to the back of the book here to find the answers. Instead, there is a continuing process of reconditioning yourself to think about situations in a new and broader way.

I have asked a client to hypothetically create a board game that represented and operated by the rules that governed the way their business currently worked. Then we went in and methodically helped the client create a whole new go-to-market strategy for a new brand. The 'rule' of the focus-group facility business is that you interview consumers in sterile environments, so that you do not influence them in any way. What we have found was that sterile environments yielded sterile responses. Consequently we have come to understand that if you wish a better chance of generating creative ideas in a professional context put people in a more natural, comfortable environment so they feel relaxed, welcomed, and at home. Not surprisingly, people are more innovative and forthcoming when that's the way they feel.

Chasing the answer doesn't allow us to pretend or imagine or to be in awe. Think about the situation at hand in broader terms than 'problem/solution.' Before you hunt answers, look for all the questions.

Exercise

Make The Rules/Break The Rules

Imagine that the situation that you're looking for a creative solution for is a game with a set of rules. Write out the set of rules.

Who are the players (as defined in the rules)?

What is the balance of power? Who has the information, and when do they have it?

Who gets involved in the process? At what point?

How does each player behave in a given circumstance?

Now question the rules. How could you shift them? What actions would you have to take to shift the balance of power? What would happen if you changed who the players were or when people got involved?

Sometimes a certain amount of pressure can be invigorating, but can you honestly say you've ever had a good idea when you were trapped at your desk, sweating bullets, and thinking about the incredibly high stakes involved in your project?

It's a different, more subtle form of fear, but it's still paralyzing. Think about a more extreme case: Imagine the plight of someone who is trapped in a panic-inducing situation. From the comfort of distance, we can wonder, 'Well, why did he run toward the fire / deadly cobras / radioactive zombies? I certainly wouldn't do that.' Scale down the panic to the stress-suffused atmosphere in your office, and you can see that under the crushing weight of seriousness, the best decisions aren't being made. When your tunnel vision is setting in, you can't evaluate or even recognize a good idea.

When the stakes are high and you desperately need a powerful idea, that's the best time to try something light and playful. Even the most senior executives seem relieved when they can lighten up - if only for 30 minutes.

Creativity and imagination require that we play, that we be relaxed and free. Being overly serious can stifle even the most creative spirit, intimidating it into never speaking out.

Exercise

Be Fanciful

Fill in the blanks. Seriously.

'What if . . . '

'I wonder . . . '

'Why don't we . . . '

'If only . . . ''I wish . . . '

'If I had a magic wand, I'd . . . '

'In a perfect world . . . '

'Wouldn't it be great if . . . '

'How could . . . '

'It might be that . . . '

Most businesses look to their competitors for benchmarking or case studies. But too often, it's easy to succumb to insular thinking: 'I've been in the widget business for 10 years; I know the widget market like nobody else. I've studied how Acme Widgets and Universal Widgets run their shops. I understand what the widget consumer needs.'

That may be laughable, but insert your top product in place of 'widgets,' and it starts to have a familiar ring.

There's a short distance between using your experience and judgment as a guide and simply trying to repeat your past successes with no new element. That's safe evolutionary thinking instead of revolutionary thinking.

To use a movie analogy, movie sequels strain to duplicate the success of the original blockbuster. They have the same stars, the same stories, the same special effects. But here's the rub: What was 'Ooooh! Ahhh!' the first time around is 'Ho hum' the second, third, fourth, and fifth times.

Revisit Enemy Two, having a fixed rather than a fluid point of view. Are you trapped in thinking like an industry giant rather than a hungry start-up? Are you creating movie sequels to products rather than thinking up new genres? You can see how this enemy of innovation fits into the pattern of all the others: no-risk logical thinking.

We encourage looking beyond rather than within an industry you may work in. Direct your focus outside the world of widgets, and think about what feedback you might get from people who are far removed from your particular field.

Exercise

Get Advice From The Outside

Imagine that you're talking to Gandhi. What would his advice be?

How about Eminem?

What about Hillary Clinton?

General Patton?

The guy who used to be your best customer?

The woman you wish were your most loyal client?

List three more people of your choice from different walks of life. What advice do they have for you?

It's everybody's job to be creative and to participate in life. Refusing to take part in the creative process immediately closes a mental door and becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy: 'I never have any ideas.'

This is yet another enemy of innovation that is rooted in fear. After we've avoided risk for long enough, we become apathetic. The creative muscles atrophy from disuse, and we forget that we ever had them. We label ourselves as 'not creative,' and then our creativity dies.

We all have a mental composite of ourselves constructed of labels, some of them positive and some negative. Once we have decided that a label fits, we limit our behavior to conform to it. We live those labels as if they were facts (scientifically provable), rather than judgments that we might be able to shift.

So, it's not your job? Make it your job. Take the risk. Take responsibility for your own creative development. Take ownership of the creative things you've done in the past. Seize opportunities to flex your creative muscles in the future.

What it all boils down to is that you need to rip off that 'not an idea person' label. The only thing that makes that label true is your own belief in it.

Exercise

Own Your Creativity

It's list-making time!

The lists don't have to be orderly and neat. Jot down anything you can think of under the following headings. What are . . .

All the great ideas I've ever had in my life: (Think about decisions like whom to marry, where to live, a great outfit you put together, the lighting fixtures you chose for your kitchen, your idea for a great vacation or outing, your way of distracting a crabby toddler.)

What I've created in my life: (Meals, great family dynamics, enough financial well-being to support yourself/others, a successful team at work.)

What I've designed: (This could be a new report at work, a new way of making kids' school lunches, a process to disengage from work at the end of the day, a Christmas letter . . . anything.)

Look at those lists. Does your tally match your assessment that you're not creative?

I'm an idea person. Given any situation, I'll have many ideas about how to make it better, more fun, more effective, more innovative. Nothing stops me cold like someone who shuts down my idea fountain.

'No, that's a bad idea.'

'That'll never work because . . . '

'We did that before, and it failed.'

It makes me absolutely crazy.

At the same time, I'm not a detail person or a process person. So while I might have a vision of what the end looks like, I'm pretty clueless about how to actually get there. I love people who'll say to me, 'Yes, cool idea. Help me brainstorm some ideas about how to solve this potential obstacle.'

When it's framed that way, I'll have some more ideas about how to overcome that barrier. The point is to use the energy derived from friction to propel a process forward, rather than having it shut somebody down completely.

If you ever study improvisational comedy, you'll find that one of the basic rules is, 'Never say no.' A comic scene needs to have conflict, but if one of the participants blocks the way, the scene is doomed. For instance, a basic comedy setup might be a person with 12 items going head-to-head with an express-lane cashier. If the shopper says, 'Fine, I'll go somewhere else,' and leaves the store, then obviously the scene is over. If either participant refuses to engage in the developing idea, then there's no point in continuing.

On the other hand, nobody wants to watch a scene in which two people agree about everything. Conflict provides interest; the key is that the conflict mustn't shut the process down.

You can see shades of all the other enemies of innovation here: fear of failure; listening for logic instead of listening for energy; 'that's the way we've always done it'; 'it's not my job.' It's a pervasive way of thinking that is difficult to break out of until you recognize it in its many forms.

In idea-generating meetings, it's important for the most senior person in the room to sincerely ask the participants for their help in creating new solutions to the given business problem or opportunity and to empower them to question the rules (even if she's the one who made them up). If this doesn't happen, the session can turn into nothing more than everyone toadying up to the senior person to see who can score the most points. When it does happen, it keeps the door open, allows friction, and creates the kind of energy that can propel a project forward. Remember, friction is good. Conflict is good. It makes things interesting.

And it provides the energetic fuel to power up new ideas.

Exercise

Keep The Door Open

When you're voicing an objection to someone else's ideas (or your own), try saying, 'Yes, I hear you. AND let's brainstorm some new solutions for a potential hurdle I'm anticipating.' Or, 'The things I like about that idea are . . . Now let's build something around those qualities.'

Think about an idea (whether yours or someone else's) that was recently rejected out of hand. Write down things that could have been said to consider the possibilities behind the idea.

We have deadlines to meet, kids to pick up, email messages to return, voicemails building up . . . let's hurry this up! Gotta go, gotta run, see you later.

It seems inefficient to take 15 minutes at the beginning of a meeting to get people emotionally engaged, to set the context appropriately, to set the right mood, to discuss how we're going to interact. And yet, if you take that 15 minutes, the meeting will have a life of its own.

Also, you have to protect against interruption. The creative process builds momentum and picks up steam. Ideas start flying, and breakthroughs happen. This buildup of energy can't take place if cell phones are ringing, people are ducking out, or supervisors are poking their heads in 'just to see how the meeting's going.'

The creative process needs to be approached in the same way you approach physical exercise. You don't run into the gym in your business suit and hop right on the Stairmaster. (Well, perhaps you do, but . . .) There's a series of steps to the ritual: You enter the gym, you proceed to the locker room, you change your clothes, you stretch, you begin to exercise. Your mental focus changes. The preparation gives you time to turn your attention and energy to the task at hand. Once you begin your workout, you don't undercut it with interruptions every other minute. If you don't build momentum, no benefits are gained.

The process of opening yourself up to new ideas is no different - there is stretching involved. Just as in working out, warming up and allowing yourself sufficient time to focus and prepare is crucial. Begin each project by deciding how long you'll spend on the divergent part of the diamond, then how much time you'll allot for the convergent side. Have team members discuss what it would take for the project to exceed their expectations and what the obstacles or dangers facing the project are. Appoint a team member to be the voice of the client or customer throughout.

You'll have better ideas, the work will get done faster, and people will be happier and more engaged. It works like magic.

Exercise

Make Time For Creativity

Schedule a few hours to work on a project away from the office.

Shut off the phones; don't answer email; turn off your pager.

Tell your administrative assistant, your staff, and your colleagues that you have an important meeting outside the office, and you'll be back in three hours.

Take your laptop or your notebook or your sketchbook, sit in a place where you feel comfortable, and write your presentation, design your brochure, write out your process plan - whatever your big project is that needs attention.

Exercise

Let's take another quick look at the enemies of innovation. They're listed on the back of this page.

Mark the two enemies that your current work environment is most guilty of. More often than not, they aren't obvious . . . they creep silently into the corporate culture like carbon monoxide: invisible, but deadly.

Now for the harder exercise: Mark the two that you, yourself, are most guilty of.

Now flip to the back of the book to find the correct answers. (How many of you fell for that, even for a brief second?)

The next step is to share this exercise with a colleague, ideally one whom you don't know very well. (Why someone you don't know very well? To help you combat Enemy Two, the fixed rather than fluid point of view, and putting yourself in someone else's mindset.)

After you're both finished, share your responses. Talk about what the experience was like for you, not about what your answers were. (We're taking a stab at the addiction to answers here. It's important to be conscious of the process at this point, not the product.)

You'll often find that you have more in common than you might suspect.

Start a meeting with this exercise. Ask each person to circle which enemy she's most guilty of and then share that with someone she doesn't know well. You'll be amazed at how the barriers melt away. (It's like throwing water on the Wicked Witch of the West.)

Keep this '10 worst enemies' list where you can see it, both when you're working alone and when you're in meetings. The first step in combating these pitfalls is to recognize them when they appear. Acknowledge that being 'sensible, cautious, and responsible' has helped you before, but you don't need it now.

It all comes back to fear. You're at the chalkboard. You have the chalk in your hand. It's your turn to answer.

Take the first action and start to move.