Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 3: Success Without Sales-Primed Communications

After reading the previous chapter, you might well be asking: Aren't some companies successful despite their reliance on the opinions of their salespeople? The answer, of course, is yes. We have learned that using the words always and never in the context of selling techniques is (usually) a bad idea.

We will extol the virtues of what we label Sales-Primed Communications. Some companies however succeeded long ago before without the application of methodology described in this resource. We think there are at least two explanations. The first is that a small number - roughly 10 percent of all salespeople - use a customer-focused approach intuitively. The second is that there are certain market conditions that make success without Sales-Primed Communications possible. This chapter describes those conditions - and also explains why it is important for almost all companies to migrate toward supporting their salespeople in positioning their offerings.

Understanding the Early Market

The early success of start-up companies or new offerings can often be attributed to the existence of one or more of the following conditions:

High percentage of early-market buyers

Significant price/performance advantage in established markets

Early successes with recognized industry leaders

Entry into a hot market space

A disproportionate percentage of customer-focused salespeople

Strong outside factors (e.g. government regulation)

Offerings whose applications are obvious to buyers

Looks like a good list, right? But look again: With the exception of the last item, all of these factors are fleeting. The first condition is a good illustration: What happens when the supply of early-market buyers is exhausted? Because of the opinions problem described in the previous chapter, companies may be ill prepared to sell their offerings to mainstream-market buyers, who over the long run buy the lion's share of an offering and ultimately determine if revenue objectives will be met.

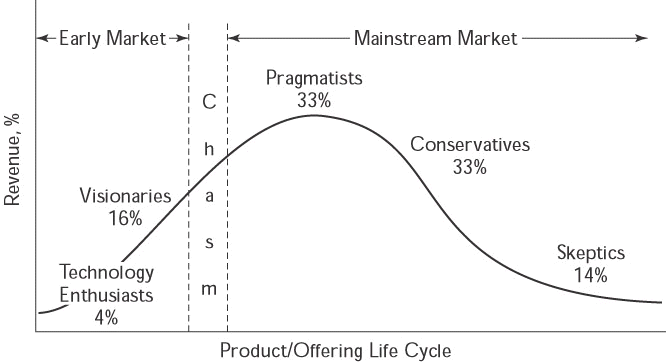

Geoffrey Moore has authored several books describing stages of market acceptance of offerings, and especially of new technologies. He offers an approach to changing Marketing's message as offerings mature. See Figure 3-1. The premise for much of Moore's work is that there are different types of likely buyers at different phases of an offering's life cycle. This may sound obvious and easy to act on, but it isn't. Even if Marketing recognizes the need to change its approach and is capable of doing so - two big ifs - how does it convey the message to the field sales reps?

Figure 3-1: Market Acceptance of New Offerings

We'd like to provide our views of the life cycle of an offering from a sales perspective.

The early-market Innovators and Early Adopters are composed of technically savvy people who are willing and able to buy from companies with a limited track record and / or offerings that few organizations have implemented. In terms of technology, early-market buyers have the ability to visualize usages and view new offerings as potential competitive advantages, if they can implement them early enough in the offering's life cycle.

Why is this interesting to us? Because early-market buyers excel in determining applications for technologies that can give them a return on their investment in those technologies. In other words, they're doing what we contend traditional salespeople don't do. They focus on uses rather than features, and this is a talent that is in short supply in most selling organizations. Early-market buyers have defined and will continue to define start-up organizations' niches.

A few years ago, we were hired as consultants to a venture capital (VC) firm that had identified specific market segments for potential investments. One of their criteria was that companies had to have shipped to at least two customers; another was that the management team (and especially the CEO) had to have a strong track record. The VC team felt comfortable in assessing these areas, but also felt that there was a missing piece in most business plans. That missing piece was a clear statement of how the potential portfolio company was going to achieve its top-line revenue projections.

Why? In our experience, people with the ability to develop new technologies and build companies around those technologies are truly gifted individuals - but those gifts tend to show up in specific areas. The habits that make them great innovators are not necessarily those that will serve them well in the marketplace. Many are so enamored of their offering - their "child" - that they have what we call the Field of Dreams mindset: "If we build it, they will come." When challenged to talk about vertical industries, applications, and potential business uses - as opposed to technical artistry - some of these brilliant innovators get defensive, or even feel insulted. Converting their creation into a business offering somehow seems beneath them.

In many of the business plans we reviewed at the request of the VC team, little thought had been given to which industries could use this new technology, which titles would be involved in the decision to buy or not buy, how the offering would be used to achieve goals or solve problems, what business objectives could be achieved through its use - and so on, and so on. In other words, very little thought had been given to how the offering was actually going to be sold.

Typically, the revenue plans assumed the acquisition of a few customers in the first year. Future revenue projections consisted of pie charts showing growth in that market segment and assumed that the company would attain an increasing percentage of that growth, and the associated revenue, over the next several years. But the mechanics of getting there, from a sales standpoint, were sorely lacking.

Companies going down this track tend to create technologies in search of markets. And unfortunately, brilliance alone is not enough. Xerox provides a powerful and sad example of a truly brilliant research-and-development operation that failed to find the applications for many of its creations. The mouse, icons, and desktop that are now used on every PC were all developed by Xerox. And yet Xerox reaped very few financial rewards for all its innovations. If you build it, they may not come to you. They may go to the company that figures out how to show buyers how to use it and sells based on that application.

Let's look a little more closely at these early-market buyers, who have the rare ability to (1) grasp new capabilities and (2) visualize how those capabilities can be used for business applications at an acceptable cost. How do they work their magic?

In most cases, it's not easy. Within larger companies, early-market visionaries face a series of challenges, even after they have identified a new technology that they feel should be implemented. If they are unable to allocate unbudgeted funds, for example, they have the ability to champion a new approach and sell one or more people within their organization on the potential benefits of this new offering.

To succeed at this, of course, they have to know the right person to approach and the right way to make the case. Most decision makers up the ladder are likely to be risk-averse, and therefore ask the question: "Why don't we wait until some other companies in our industry validate the approach?"

Our experience suggests, however, that early-market visionaries control (or can get access to) adequate funds. As a result, most early purchases are made impulsively, without extensive debate. In other words, gut instincts play a much larger role than formal cost-benefit analyses.

Early-market buyers are willing to endure the inconveniences and disruptions that almost always come along with being first-generation customers. Potential problem areas include poor product reliability; inadequate training, documentation, and support staff; missing functionalities; and so on. Early-market buyers often participate in identifying these kinds of problems, and in making suggestions about possible improvements. In fact, these customers sometimes use their position to drive product development in directions that will be most advantageous to their own agenda. In such cases, they're unlikely to be worrying about what the requirements of mainstream-market buyers may be.

Assuming you want early-market buyers - and in most cases, you should - how do you find them? It's not easy. The best approach we've seen is to try to get exposure for new offerings by asking Marketing to create "buzz," and then to wait for the early-market buyers to find you. If your product is good and the buzz is adequate, they will find you. And when they do, you'll be in good shape, because early-market buyers buy. They don't need to be sold.

Beyond that, early-market buyers are often found at small to mid-size companies (or divisions of large companies) that (1) have minimal red tape and (2) aren't burdened by the need to get a consensus to make a somewhat adventurous buying decision. Like venture capitalists, these buyers understand and accept that some decisions will not achieve the desired results. Let's say that they make ten buying decisions. If two exceed expectations and six are moderately successful, they can easily tolerate two mistakes. They can be confident that the advantages accruing from those two good decisions will outweigh the write-offs.

When implementing a new offering, early-market buyers generally have the expertise to integrate the new technology into their current environment. Let's take a humble example on the retail level. An early- market audiophile assembling a sound system would research all options, focusing on recently announced offerings and also considering lesser-known companies. The best individual components would be chosen, and the task of integrating them would begin. The early-market audiophile would buy (or make) the necessary interface cables, and might even make a custom cabinet to house the system.

Understanding Mainstream-Market Buyers

Mainstream-market buyers, by contrast, would buy a consumers' guide, go to a national electronics chain store, and buy a standard package, complete with mounting brackets for the speakers, cables, prebuilt cabinet, instructions, and so on. The mainstream-market buyer is willing to pay extra to have the system delivered and installed. He or she may take out an extended warranty for extra peace of mind.

Few of them will admit it, but mainstream-market buyers don't want the latest technology. The concept of being first, or even early, is an unpleasant one. Their comfort zone lies being in the middle of the pack - following, not leading. They focus on issues that the early-market buyer either doesn't consider or minimizes. For example:

Is this a proven offering?

What is the track record of this company?

Who are the more established competitors playing in this space?

Will this offering become a de facto standard for my industry?

Who else in my industry is using it?

What business results have others achieved?

What will the return on investment (ROI) on this project be?

What do industry experts think about this offering?

Can we get consensus from an evaluation committee?

What type of support will we get during implementation?

Is my career at risk by committing too early in the product life cycle?

Is making no decision better than making the wrong decision?

Prior to making decisions, mainstream-market buyers need to make comparisons. Getting a minimum of three bids, for example, may be corporate policy. If your offering is so unique that there are no vendors to compare it to, the evaluation may come to a grinding halt, because the mainstream-market buyers cannot validate that they are making the right decision.

If other vendors can be assembled, they may be more established than you are. If they don't have an offering ready, they may sow seeds of doubt with the buyer about committing early to a little-known company (i.e., yours) and a technology that has not been accepted as a de facto standard. Larger companies refer to this strategy as "sowing FUD" (fear, uncertainty, and doubt), and employ it to scare mainstream-market buyers into a "no decision" posture - giving them time to come up with their own offering.

Prior to signing, mainstream-market buyers may want a cost-benefit analysis of a potentially risky expenditure. In most cases, it will be incumbent on the vendor to help facilitate these calculations. Salespeople who don't fully understand how buyers can use their offering will have difficulty facilitating this analysis.

And finally, mainstream-market buyers often require references and reassurances that the early market doesn't ask for. Typical requests made by mainstream-market buyers prior to making a buying decision include

Vendor contractual guarantees

Delayed payment contingent on performance

Meetings with your senior executives

Prototypes or free evaluations

Headquarters visits

Crossing the Chasm

While early-market buyers can serve as a start-up's lifeblood for the first several months, longer-term revenue objectives (a much larger piece of the revenue pie chart) cannot be realized within this segment, which makes up only a small percentage of the overall market.

Companies remain in the early-market stage for offerings within vertical markets until they establish a beachhead consisting of a critical mass of customers who can provide credible references. These are invaluable in emboldening the initial mainstream-market buyers - the "early majority" - to evaluate and consider making a buying decision. Eventually, if all goes well, these buyers are followed by other groups of mainstream-market buyers: the "late majority" and - very late in the cycle - the "laggards."

Even in the case of horizontal offerings - that is, products that are applicable universally, rather than to a particular vertical segment - mainstream-market buyers respond best when selling organizations appear focused on their particular vertical segment. An example of a horizontal offering would be e-commerce software that applies to a wide range of businesses. If you are selling this product to a mainstream-market catalog retailer of clothing, for example, they are likely to be most comfortable with you if your company has already sold to other customers in their market segment. The fact that you've sold successfully to, say, a tire manufacturer isn't likely to carry much weight with them - even if the product is equally as applicable to selling tires as to selling clothes.

After the initial missionary sales effort - often accomplished through heavy involvement by the founders and intensive product redevelopment - the following months can be heady ones. Sales come more easily, and momentum is established. Customers are providing validation with their checkbooks, and this feels good. The sales team now begins a round of recruiting, to handle what they perceive to be increasing demand.

The company is now approaching the chasm between the early and mainstream markets. To get across this chasm, the company needs to be sure that at least two fundamentals are in place: (1) the new offering has been proven functional and reliable, and (2) there have been quantifiable results. With these two criteria met, and with a sales force that is up to the new challenge - a subject to which we'll return below - the company is ready to attempt to penetrate the mainstream market, which usually represents something like 80 percent of the market potential.

An example of the chasm can be seen in the artificial intelligence (AI) industry of the early 1980s. This industry comprised disruptive technologies that could be used in all sorts of ways. The early market (think tanks, universities, and so on) saw this potential and bought the products. Purchases were not usually based on near-term business applications; rather, they were made to allow organizations to explore. Many traditional salespeople who represented companies with a competitive product killed their quotas and cashed huge commission checks.

This wave of buying and euphoria lasted about 18 months. Then, suddenly the superstars couldn't achieve 50 percent of their numbers. While there certainly were other factors at work, one underlying problem was that the artificial intelligence companies failed to cross the chasm. They never showed the mainstream market why the offerings were needed, and how they could be used to achieve improved business results. Artificial intelligence has been recovering from this debacle ever since. Decades later, AI has made a modest reentry into the marketplace.

Unfortunately, getting across the chasm is not an optional exercise, nor can it be done at a casual pace. Failure to execute this phase of the larger business plan will adversely affect revenue. Delays may afford competitors an opportunity to catch up, and may fritter away whatever first-mover advantage the company may have had.

Postchasm Sellers

Mainstream-market buyers, as suggested above, prefer to follow rather than lead. In adopting that attitude, of course, they're simply being human. Mainstream humans crave predictability. We want to know what we're getting into. How often do you go to see a play, try a new restaurant, or read a book that you know absolutely nothing about? An enthusiastic recommendation from a personal acquaintance, or a trusted reviewer in online media, dramatically increases the probability that you'll sample this new offering.

In fact, there are whole industries devoted to providing these kinds of recommendations and assurances. Think of all the movie critics, travel guides, consumer magazines, and so on that are alive and prospering.

We've already alluded to the need for a prepared sales force, able to align with and enable this more plodding and cautious buyer. A danger at this stage in a company's development is that success in selling early-market buyers often has been achieved by evangelizing a leading-edge offering, and by metaphorically challenging buyers to "be the first one on the block" to have it. But as they say of generals, the great temptation is always to fight the last war. Early-market buyers can make traditional sellers seem brilliant - that is, look customer-focused - because they buy. But in many cases, they buy despite the product pitches. For the mainstream-market buyer, the leading edge sounds too much like the bleeding edge - in other words, a thing to stay away from.

What of the sellers? In many cases, a good percentage of the initial salespeople hired were naturally customer-focused. They may have been recruited by the founders themselves, and incentivized (through the use of lucrative stock options) to take a high-risk, high-reward gamble. But as revenues grow and some of these top performers accept promotions into sales management, a shift begins to take place within the organization.

As the company begins to migrate from start-up to going concern, stock options for new salespeople become less generous. An initial public offering (IPO) can be great for those salespeople with founding stock; it does little for those who join the company after the IPO. Compensation similarly tends to become more bureaucratized and less lucrative. Senior executives, meanwhile, are preoccupied with building and running the business, and perhaps with keeping Wall Street happy. They are less likely to be recruiting salespeople personally and making sales calls.

The net result of all these changes? The sales talent that the company was able to initially attract and hire begins a downward spiral.

Newly promoted managers - that is, those who were responsible for early sales results - now are responsible for hiring new salespeople. In many cases, this is a task for which they are ill prepared and temperamentally unsuited. Even if they were customer-focused salespeople in their former incarnations, how do they evaluate the skill sets and chances of success of candidates they interview? Will insecurity in their new positions tempt them to hire less talented people who won't be a threat? In our experience, the answer is often yes. Many 10s (highly talented people) hire 9s, who hire 8s, and so on.

Winging It

The major difficulty with the selling environment we've described so far is that few companies develop a repeatable way for traditional salespeople to navigate buying cycles with mainstream-market buyers. Instead, they offer disparate silos of product and industry knowledge, backed up by more or less irrelevant sales collateral. Ultimately, in the absence of a workable structure, salespeople have no choice but to wing it. Revenue growth stagnates, and no one can explain how or why.

Contrast this with other occupations. For example, you won't find plumbers or electricians winging it. They are required to take courses and get certified. Most serve an apprenticeship, working under someone who is experienced. Finally, jobs have specifications showing which materials will be used, drawings that define how the work will be done, on-site supervisors or postjob building inspectors who monitor quality, and so on. All these factors combine to create a structure designed to ensure that (1) the worker is competent and (2) the outcome is predictable and satisfactory.

Why do so many salespeople wing it? We believe it's because in most cases, there is no clearly defined structure within which salespeople can operate. Expectations (beyond achieving quota) are vague; a definition of a standard sales process is almost nonexistent.

Don't believe us? Based on your own experience in sales, try this experiment: Get out your laptop, and take a moment to write down the steps you follow in selling to a prospect. (If you aren't in sales, ask someone who you believe is a competent salesperson to perform this exercise for you.)

Now look at that document. If your son or daughter were just starting a sales career, how helpful would this description of selling be? Does it give specific direction about how to sell? If your son and your daughter went off to sell the same product based on your document, how similar would those two sales efforts be?

The underlying reason most traditional salespeople wing it is that their sponsoring organizations haven't codified the selling process. So - as discussed earlier - the positioning of offerings is abdicated to salespeople, even though it never appears (and doesn't belong) in their job descriptions.

What about the Naturals?

As we've already pointed out, some salespeople are exceptionally talented, in the sense of being naturally customer-focused. Our best guess is that they make up about 10 percent of the sales population. These are gifted, intuitive salespeople, with the remarkable ability to transform (mostly irrelevant) product training into a coherent message - one that is tailored to the title and function of the person they are calling on.

To reiterate: Calls made by customer-focused sellers are conversational. These salespeople relate to buyers, establishing their credibility by asking intelligent questions. Rather than leading with offerings, customer-focused salespeople ask questions. They seek to understand a buyer's needs, so that they can focus on the parts of their offerings that provide a fit. By so doing, they are preparing buyers to want what they are going to offer, later in the conversation.

Naturally customer-focused sellers are the only salespeople who are capable of doing an adequate job of positioning offerings without Sales-Primed Communications. Their opinions of what is qualified and what will close can be taken to the bank. (Even customer-focused sellers, we should note, may have trouble forecasting when opportunities will close.) They rarely waste time - yours or theirs - on unqualified opportunities.

Customer-focused salespeople need minimal coaching. After completing new-hire training, they find the best product and support people, and pick their brains to understand what this offering allows the buyer to do. customer-focused sellers make their first sale quickly, and most make their numbers the first year. In subsequent years, they almost always exceed whatever quota they are assigned.

Some organizations, having spotted this pattern, conclude that the best approach is to recruit and hire only naturally customer-focused salespeople. Two problems: First, there are not enough to go around. And second, customer-focused sellers are selective about the types of companies they join. They know how good they are. As a rule, they seek smaller companies. They like to be recruited and interviewed by senior executives. They want situations with equity and highly leveraged compensation plans, reflecting the difficulty of selling the first several accounts. They do not want to be managed, they hate red tape, and they like to have the freedom to do whatever it takes to get the business - even if that sometimes means stepping on toes internally. This means, therefore, that companies that don't fit this description have to either develop their own customer-focused salespeople or do without.

When asked to summarize the difference between customer-focused and traditional sellers in a single word, we respond, "Patience." Customer-focused salespeople are patient; traditional sellers are not. Once a buyer shares a goal or reveals an organizational problem, traditional salespeople launch into a "here's what you need" product pitch. This creates problems at several levels:

Most people don't like to be told what to do or think. This is especially true when the person telling you what to do is a salesperson - who almost always has a quota to meet, and therefore can't be seen as an objective party.

When assaulted by a "spray and pray" pitch, buyers are likely to realize that there are features in this offering that they don't need. The conclusion that the offering is too complicated, and therefore too expensive, may not be far behind.

By failing to ask good questions and listen, the traditional salesperson fails to understand the buyer's current environment and the reasons he or she cannot accomplish the goal or solve the problem being discussed.

Similarly, the traditional salesperson has no way of discovering if the offering is a good fit with the buyer's needs. The buyer hasn't been allowed to describe his or her current situation. Failure to understand the customer environment leaves the door to misset expectations wide open.

Customer-focused sellers, by contrast, are patient. They ask buyers why they are having trouble accomplishing the stated goal. They dig into the barriers that are standing in the way of a solution. By so doing, they can home in on the capabilities of their offering that may actually help the buyer.

Punished for Success

Imagine that a company has grown to the point where it is time to open a new branch office. The decision has been made to promote a salesperson from within the company to be a sales manager. Whom do you think they'll turn to? Do you think they will promote a salesperson who has struggled to hit 100 percent of quota, year in and year out? Or do you think they will promote someone who has consistently exceeded quota?

Almost universally, companies promote their top-performing sellers. This may seem like the right thing to do, but in fact, it most often creates a whole new set of problems:

A top-producing salesperson is removed from a territory, and sales and relationships may suffer.

In the absence of a sales structure, as described above, a top-producing salesperson is likely to make a rotten sales manager, and may make life miserable for those reporting to him or her.

This may be the first job in which the top-producing seller fails. Many first-year sales managers go from a hero (top-performing salesperson) to a zero (bottom-third performance as a manager). As a result, he or she may ultimately leave the company.

The skill set needed to teach traditional salespeople to be customer-focused is vastly different from the skill set needed to perform as a top-producing salesperson in a territory. customer-focused salespeople have an Achilles heel, which rarely shows up until they are promoted to sales manager: They don't know what has made them successful. They were intuitive; it "just happened" for them. They have never broken down what they do into understandable (teachable) components.

For that reason, they tend to tell their direct reports what to do, not how to do it. They've never been asked to be articulate about their work; now they're expected to be. Imagine NBA star LeBron James becoming a coach. He tries to explain to an average basketball player how to do a 360-degree turn while hanging in the air, switch the ball from the right to the left hand, go under the basket, and put reverse spin on the ball so that it will carom off the backboard and drop into the hoop. Unlikely! As an individual performer, James does his thing, and the rest of us admire his artistry and athleticism.

Think about the athletes who become outstanding coaches. Many of them were average players, at best. It didn't come naturally for them. Because they lacked the talent of a LeBron James, they had to plod along and learn all aspects of the game. As a direct result, they set themselves up to be better teachers. Average performers are process-friendly. They are more likely to be patient with other average people, and therefore, they are more likely to help them improve.

The newly promoted top producer, as described above, has always hated the administrative aspects of selling. Now, thanks to this promotion, he or she is expected to spend 20 to 30 percent of his or her time performing these tasks. Promoting a top-performing salesperson to sales manager is analogous to "promoting" a Top Gun pilot to air traffic controller. It's taking them out of a realm in which they are almost certain to succeed, and putting them into a realm in which they are almost certain to fail. In effect, it's punishing them for their past successes.

A Changing Context

Meanwhile, our former Top Guns find themselves in a changing context. As the ranks of salespeople swell, the percentage of top performers declines. The company begins the task of creating and implementing policies, procedures, and structure.

As the landscape shifts to the mainstream market, new sales managers may start to find that they no longer have the same flexibility in pricing and terms that they enjoyed when they were enticing early customers to sign. The customer base is changing, too. As we've seen, early-market buying behavior is driven by a small number of participants, sometimes even by one primary supporter. A high percentage of early customers were small to mid-size companies.

Now, senior management is determined to pursue larger transactions at larger companies. These are very different beasts, with multiple layers of management, infrastructure, and so on. Mainstream-market buying involves a larger number of people, often through a committee structure, and often entails the need to gain consensus. (In some cases, a majority prevails, but in the worst case, decisions must be unanimous.) Even in a case where the committee concludes that an offering is viable, there may be a delay until other options are considered - for example, a request for proposal (RFP) that is distributed to multiple vendors. Mainstream-market buyers are pragmatists. They believe in due diligence. As a seller, you may even be punished for your uniqueness: Mainstream-market buyers sometimes defer a decision indefinitely because they are unable to evaluate alternatives.

Meanwhile, as the sales organization grows, the Marketing department expands (or is organized for the first time). Its objective is to shape the way prospects are approached by standardizing product presentations and brochures. There is an attempt to codify how offerings are sold. What began as handwritten notes on a cocktail napkin by the founder early in the company's history is now a glossy six-color brochure, bursting with high-end graphics and ambiguous terms: leading edge, robust, synergistic, scalable, seamless, state of the art, and so on.

These marketing efforts are often flawed because they tend to be based on successes with early-market buyers who didn't need to be sold. The deliverables to the field are product-intense, treating offerings as nouns rather than verbs. But the strengths embraced by the early market - and now highlighted in the newly created collateral materials - may be out of alignment with the concerns of pragmatic buyers. In fact, they may raise issues that will be barriers to getting buying decisions made.

In this changing context, the danger lies in not knowing when or how to change the selling approach. Leading with features was (sometimes) acceptable with the early-market buyers. But leading with features when approaching mainstream-market buyers is deadly poison. Telling them that this is the latest technology, and that they'll be the first on their block to have it, is simply too scary for them.

The 72 Percent Zone

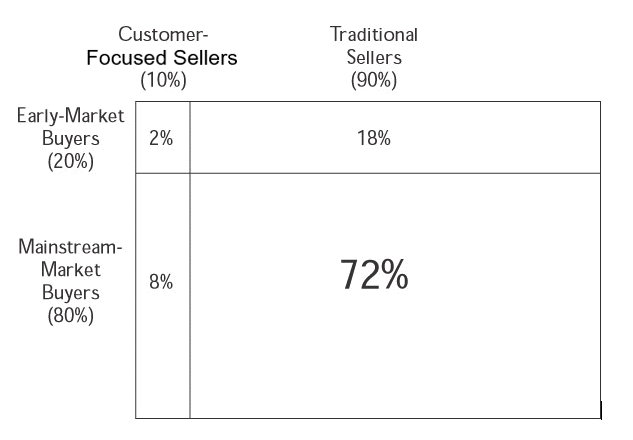

Now let's look at Figure 3-2. If you create a standard two-by-two grid, segmenting salespeople and buyers into two categories, you come up with four possible buyer/seller combinations.

Figure 3-2: Who Ends Up Selling to Whom?

This grid shows how 100 percent of all selling situations are distributed across our four combinations. For example, if early-market buyers are 20 percent of selling situations and customer-focused salespeople are 10 percent, then that combination results in 2 percent of the overall total.

In other words, 2 percent of selling situations consist of customer-focused sellers calling on early-market buyers. This situation yields the highest ratio of success. In fact, it may be overkill, because the early market typically buys; it doesn't have to be sold.

Similarly, 18 percent of selling situations consist of traditional sellers calling on early-market buyers. Let's assume the traditional salesperson is capable of delivering the standard PowerPoint presentation that describes the new offering as if it were a noun. Early-market buyers are willing to endure a "spray and pray," and are also capable of determining if this offering can be used to their benefit. Despite the fact that the salesperson cannot describe how the offering could be used, the vendor still has a high probability of a sale. The biggest challenge, in this case, is finding those early-market buyers.

In 8 percent of selling situations, customer-focused sellers are calling on mainstream-market buyers. This is the best use of a customer-focused seller's talents. The mainstream-market buyers need help in understanding what the offering will enable them to do, and how they will benefit as a result. The customer-focused seller has the ability and patience to navigate through the buying cycle and maximize the chances of getting the business.

The most disturbing fact that emerges from this chart is that 72 percent of the time, salespeople who are selling risk (that is, focusing on technology and features) are calling on people (mainstream-market buyers) who are highly risk-averse.

Buying cycles with this combination are arduous, at best. In our 72 percent zone, a far higher percentage of sell cycles end with no decision. For example, in our experience, information technology vendors selling to the mainstream market win about 15 percent of opportunities that go to the end of a decision cycle, and another 15 percent of the time, a competitive vendor wins. But in a discouraging 70 percent of these situations, buyers make no decision at all.

In the late 1990s, vendors of technology had the huge advantage of the looming Y2K threat, which forced mainstream-market buyers to make decisions in a hurry. Absent that kind of external pressure, these buyers would have been far less likely to move - and the salespeople of the day would have had far less reason to be smug.

We worked with a CEO who concluded that there was no early market for his company's offerings - that is, no easy sell. He then took it a step further: He also concluded he had no customer-focused sellers within his sales organization. His calculation of who was calling on whom was simple: 100 percent of his sales situations were the least desirable - traditional salespeople calling on mainstream-market buyers, which can be considered as having the inept call on the unable.

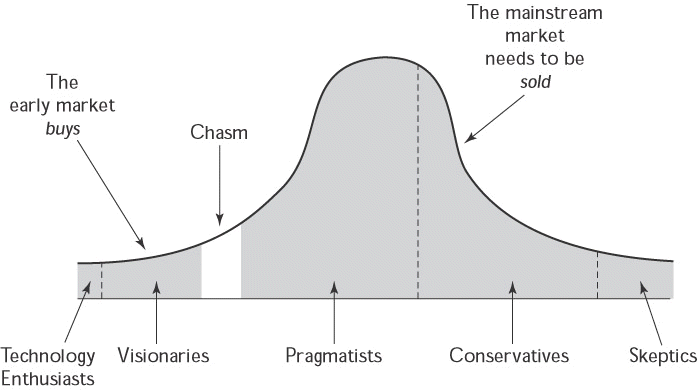

Figure 3-3 is simply another way of illustrating that the majority of a potential market is postchasm and that therefore potential buyers are unable to understand on their own why they need a new capability or technology, or how they might use it. For companies selling technology, delays in crossing the chasm can be devastating. While most everyone would agree that delays provide competitors time to catch up and adversely affect overall market share, many have not considered the impact of price erosion as a technology goes through its life cycle. Companies with unique offerings can command a premium, but as other companies enter the market, there is a tendency to migrate toward commodity pricing. In the late stages of a product's life cycle, reduced pricing is often the tactic to stay competitive with newer technologies. Companies failing to cross the chasm are adversely affected by both lower market share and margins.

Figure 3-3: Waiting for the Mainstream Market to "Get It"

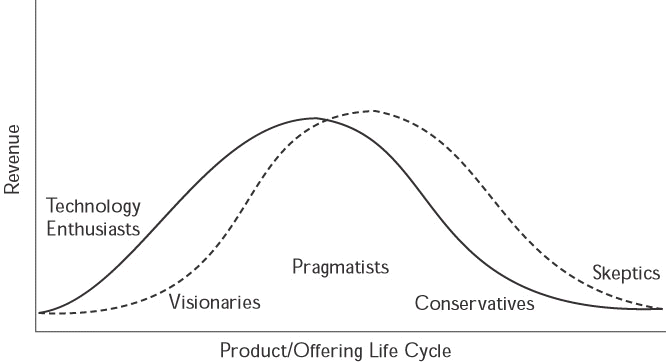

We tell our clients that if they start preparing to sell to the early majority (the pragmatist) from day one, they can virtually eliminate the chasm and change the shape of the bell curve in Figure 3-3 by bringing in mainstream-market sales sooner. Note in Figure 3-4 that the duration of the product life cycle does not change but that now the categories of buyers can be sold to concurrently rather than serially. By empowering traditional salespeople to have conversations about usage with Key Players, Marketing can accelerate acceptance and market share at higher margins. If time to revenue is the question, then Sales-Primed Communications from day one is the answer.

Figure 3-4: Eliminating the Chasm: Helping the Mainstream Market "Get It" by Incorporating Sales-Primed Communications into Product Launches (Solid line curve = without chasm; broken line curve = with chasm)

What happens when a company fails to drive top-line revenues? The most common result is mutual finger pointing by Sales and Marketing. We believe that both Sales and Marketing have failed to do their jobs. Traditionally, there is a great deal of tension, even conflict, between these two functional areas. Later in this resource, we'll explore this relationship more closely, and offer a definition of an appropriate interface between Sales and Marketing.

In summary, there are circumstances in which new offerings can enjoy success even without Sales-Primed Communications being made available to their sales organization. As markets and sales organizations mature, however, penetration of the mainstream market almost always proves to be more challenging (a.k.a. "hard rock mining"). To sustain success, companies have to realize how different mainstream-market buyers really are, and act on that insight.

Mainstream-market buyers don't buy; they need help in understanding how an offering can enable them to achieve a goal, solve a problem, or satisfy a need. So, companies can maximize their chances of prospering if they enable their growing number of salespeople to have conversations with buyers in a way that positions offerings more consistently, leveraging best practices.