Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Brochures and Collateral

Just as traditional salespeople feel compelled to "spray and pray" when contacting prospects, so do most brochures and collateral literature. Many are little more than product specifications, often with some graphics and a sampling of nebulous terms (seamless, robust, synergistic, leading edge, and the like) thrown in to make them slightly more readable.

But this is silly. When you go fishing, you choose a specific location, type of bait, type of hook, and method (trolling, casting, and so on), all based on the particular type of fish you are attempting to catch, right? Why would you not do as much, or more, when trolling for prospects?

Here's a useful exercise: Pick up a piece of collateral that is likely to be sent to a prospect, and turn the pages. As you do, ask yourself:

What level within the organization would want to read this?

Can this level allocate unbudgeted funds?

What business issues does the collateral attempt to raise?

What action is it intended to prompt?

Yes, there is always a role for strong technical information—but is it something you want to lead with, in attempting to get an entry point into a prospect organization? In most cases, the answer is no. Brochures with extensive technical detail are best at (1) answering a deep question from an expert, (2) informing those who are not decision makers about your offerings, and (3) reinforcing credibility that you've built up in other ways.

Another generally deadly approach is to provide traditional salespeople with glossy "pocket folders," that is, large folders into which smaller brochures, letters, and business cards are inserted. In many cases, when a prospect asks, "Can you send me some information?" traditional salespeople start emptying out their drawers of printed material. The result? Five dollars in printing out the door and a three-dollar charge for the mailing, at the end of which buyers feel that they have received too much information (TMI) and therefore don't read much (or any) of the material. (We hear this story all the time as we follow up on clients' salespeople.) This, in turn, prompts the classic response from the prospect's assistant: "I'm sure she's seen it, and if there is any interest, she'll get back to you."

We don't recommend putting this prospect on your forecast. Does it belong there?

Of course, Marketing can reduce this exposure to some extent by being selective about the types of collateral it produces. But in addition, we suggest that when they receive requests for information, salespeople respond by asking for a brief discussion to better understand the buyer's area of interest, so that they can send only material that is germane. It doesn't hurt to be explicit about this: "We have lots of offerings with different capabilities, and we'd prefer not to subject you to saturation bombing. What, exactly, do you want to know about?" Another alternative is to ask the buyer: "What are you hoping to accomplish?"

Here are some possible alternatives to spec sheets and too many brochures falling out of pocket folders:

Menus of business goals or problems

Success Stories

Sample cost-benefit results achieved by customers

Note that the menus of business goals or problems can be taken directly from a Targeted Conversations List, as described in the last chapter. The point of the menu approach, of course, is to allow sellers to use examples of common business problems to lead the buyer into a discussion. It's often easier for the buyer to say, "Hey—we have this same problem!" than to say, "Let me describe this odd problem we, and only we, seem to be having."

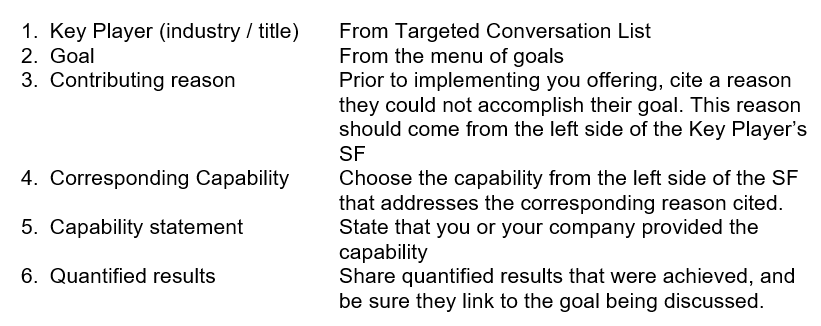

Success Stories are one of the oldest techniques in the sales profession. For understandable reasons, buyers are much more comfortable if they are not among the first to buy the seller's offering. Keeping in mind the concept of product usage and Targeted Conversations, consider the Customer Focused Selling Success Story format in Figure 9-2.

Note that the first two components (Key Player and Goal) are from a Targeted Conversations List. Once a seller gets a buyer to share a goal, the next element is a "contributing reason" for the customer's not being able to achieve the goal. This reason is naturally aligned with a capability. The benefit statement now allows the seller to finally say, "We gave him that capability," and then finishes with the actual benefit derived from the customer's use of the offering.

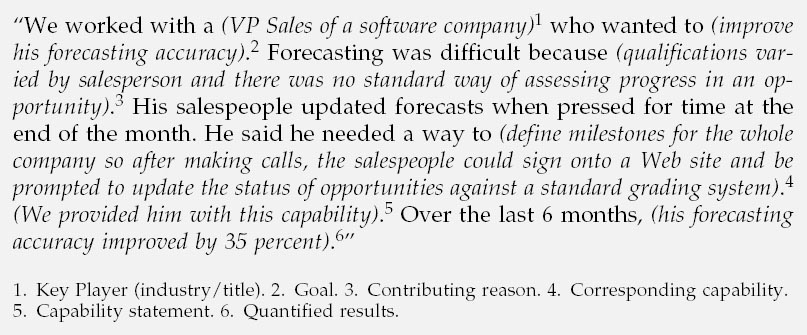

In Figure 9-3, we have reproduced an actual Customer Focused Selling client Success Story. This particular client sells a host of manufacturing productivity-enhancing products and services, and the Key Player and goal are from their Targeted Conversations List. The contributing reason is aligned with one of their key capabilities: early warning notifications. After their salesperson delivers a benefit statement, she can then finish by quantifying the actual financial benefit.

Note that this Success Story was crafted by Marketing, published by Marketing, used by the Training department in training salespeople, and

finally used by the salespeople when engaging potential new prospects. This is the kind of collaboration that leads to sales success.

The third alternative to the standard collaterals listed above is sample cost-benefit results achieved by customers. These can be extremely powerful tools, because they let customers speak to customers, without any intermediation by the salesperson.