Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 17: Driving Revenue via Channels

Over the past several years, many organizations have chosen to supplement their direct sales forces with—or even rely exclusively on—sales channels to drive top-line revenue. These indirect organizations include value-added resellers (VARs), distributors, and partners, to which we'll refer collectively as "channels."

These salespeople are not employees of the companies whose offerings they represent and sell. Microsoft is one of the most notable successes in driving a high percentage of their nonretail business through channels. Their channels have not only provided sales presence, but have also allowed Microsoft to minimize the hiring of technical support people to assist in implementations. This approach has been vastly different from that of many other technology companies, which have added support staff as direct employees.

Getting the Right Coverage

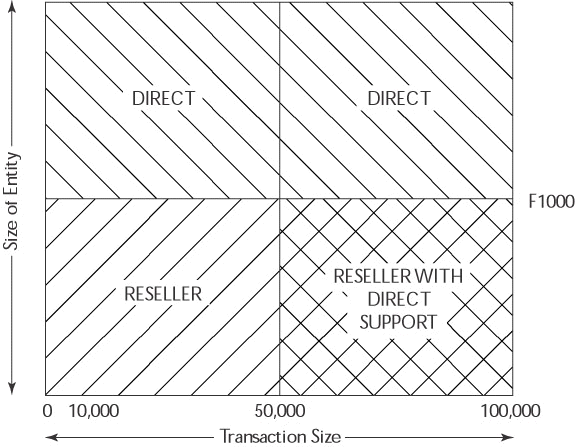

For companies that are attempting to use both direct and indirect salespeople, one of the challenges is to define which market segments should be assigned to each, in order to maximize coverage and minimize conflict. We worked with a client selling software ranging from under $10,000 to more than $500,000 who utilized both a direct and an indirect sales approach. We helped them define the desired coverage by working through the chart in Figure 17-1.

The criteria used to determine responsibility were account size on the y axis (with the Fortune 1000 being a threshold) and opportunity size on the x axis, with $50,000 or higher being designated as a major opportunity and below $10,000 being handled over the phone exclusively. Everyone was comfortable with his or her strategy, and we agreed that it was well thought out.

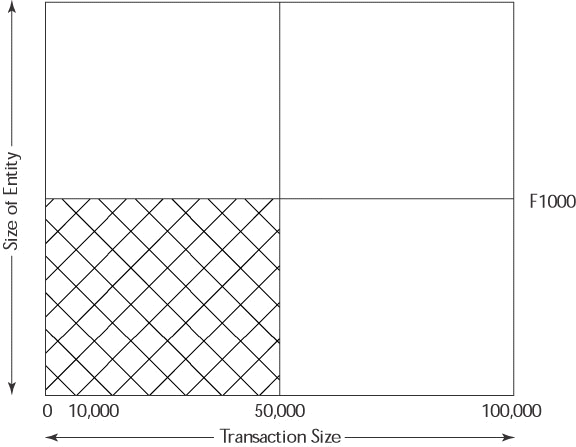

After we had collectively defined the desired coverage, the next logical question to ask was, "What does the actual coverage look like, today, in the field?" The room was quiet for a few moments. Finally, the most senior executive in the conference room volunteered his opinion—subsequently endorsed by everyone else—that the most extensive coverage was in the quadrant of non-Fortune 1000 accounts under $50,000 (see Figure 17-2).

Further discussion brought out the fact that most of the company's salespeople (both direct and indirect) were engineers who were most comfortable calling on engineers—for the most part, non-decision makers. Interestingly enough, their direct salespeople were receiving an override on sales made by the channel. In some cases, in fact, direct salespeople were achieving quota while closing little or nothing themselves.

Gradually, it emerged that the firm's underlying problems lay in two areas. The first was that their direct salespeople did not know how to position their offerings for nontechnical business people. Sales-Primed Communications and a sales process were used to address this issue.

The second problem was inconsistency and conflict between the desired coverage and the compensation plan. While management can make their wishes known, the best way to influence a salesperson's behavior is to reinforce it with a commission structure. Part of the reason for the decision to implement an indirect channel was to decrease the cost of sales. But in their current situation, the company was actually paying duplicate commissions to both direct and indirect salespeople on most transactions.

By implementing recommendations, direct salespeople were weaned from their overrides on sales by the channel over 6 months. After that time, the commission plan structure drove them to pursue only Fortune 1000 accounts. When some direct salespeople were unwilling or unable to execute these enterprise sales efforts, they were encouraged to join VARs so that they could continue selling within their comfort zones for small to mid-size opportunities. The channel was given a different compensation structure, receiving 100 percent commission for sales to non-Fortune 1000 accounts that did not require sales support from the manufacturer. They could request support on sales of over $50,000, but in these cases they received only 80 percent of their sales commission.