|

|

A Discipline for Enterprise Sales

The discipline with which top performing salespeople approach their work is perhaps the most critical component of their success. Just as the assumptions inherent in traditional sales methodology doom those who accept them to ineffectiveness and miscommunication, the mental framework with which we approach the enterprise sale acts as the enabler of all that follows. Mind-set is the starting gate of enterprise sales success. Without the mind-set or point of view, the best laid skills or tactics will fall flat on their face.

Three statements summarize, in broad terms, the discipline of enterprise sales:

-

The most successful people in enterprise sales recognize that for their customers, the process of buying goods and services is all about making a decision to change. When they are working with a customer, they are actually helping that customer navigate through the change process.

All too often, a sales professional uncovers a serious problem the customer is experiencing, which the customer agrees is a problem, and wants to solve. They have discussed the solution options, and the customer agrees that the solution can eliminate the problem, yet they do not buy. Why does this occur? It's not that the customer doesn't have a problem, and it's not that you don't have a solution. It occurs because the customer cannot or will not go through the personal or organizational changes needed to implement the solution.

Every purchase is based on a customer's decision to change. In simple sales, the customer's decision and the change process is often transparent, but it does take place. At a most elemental level, even a purchase of paper for the copy machine involves a degree of change. "I notice we're out of paper; call my supplier or go to the Web and order the paper and restock the cabinet." The decision was simple - a repeat purchase and not much thought needed to go into it. No muss, no fuss. However, change did take place. I went from no paper to ample supply, I'm more relaxed about the upcoming reports to be copied and distributed, and my bank balance or available budget dropped by a few dollars.

In simple sales, a salesperson can ignore customers' change process, comfortable that customers will navigate the elements of change on their own. Elements of the decision and changes involved with the purchase are clear to the customer. Thus, the customer understands the risk involved in the change, and resistance to making the change is low. But what happens when the complexity of the sale increases in a business-to-business transaction? The decision elements of the situation and the changes involved in the purchase are more complicated and more difficult to understand. The risk of changing is higher. The investment, the requirements of implementation, and the emotional elements - the impact on the buyer's career and livelihood - all create a higher risk of change. Accordingly, resistance to change is substantially higher. Change and risk management now play a major role in the decision and subsequent sale.

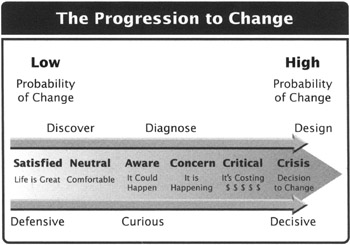

The more complicated a sale becomes, the more radical the change the customer must undertake and the greater the perceived, as well as actual, risk. A conventional salesperson, who is solely focused on presenting and selling his or her solutions, is ignoring the critical elements of decision, risk, and change in the enterprise sale. The most successful salespeople, on the other hand, are noted for their ability to understand and guide the customer's change progression (see Figure 3.1).

There is a large body of psychological and organizational research concerning the dynamics of change. A key insight is that the decision to change is usually made as a response to negative situations and, thus, is driven by negative emotions. People change when they feel dissatisfied, fearful, and/or pressured by their current problems. Similarly, customers are more likely to buy in those same circumstances. Conversely, people who are satisfied with their current situation are unlikely to change and are unlikely to buy.

The best salespeople understand that all customers are located somewhere along a change spectrum. They work with customers to identify and understand their areas of dissatisfaction, to quantify the dollar impact of the absence of a solution, and to design the optimum solution.

What happens when salespeople ignore the Progression to Change (see Table 3.1)? Here is a common scenario: The salesperson focuses on selling the future benefits of his offering. He does a wonderful job presenting, eventually lifting the customer to a euphoric peak with his exciting and unique solution. It is the perfect time to close and, of course, that is exactly what our salesperson attempts to do. What happens next? The customer, being asked to commit, is literally shocked out of his gaze into the utopian future and confronted with the current reality of all the risks and issues of change. Then come the objections, and the resistance to change rears its ugly head. The sales process slows down, and the sale, which the salesperson thought was "in the bag," is in serious jeopardy of being lost.

|

Satisfied |

"Life is great!" Customers have strong feelings of success. They feel their situation is very good and see no need to change. |

|

Neutral |

"I'm comfortable." Customers have no conscious feelings of satisfaction or pain. They are not actively exploring their problems; they are not considering change. |

|

Aware |

"It could happen to me." Customers have some discomfort. They understand that a problem exists and that they may have some exposure, but it is not directly connected to their situations. They may consider change in the future. |

|

Concerned |

"It is happening to me." Customers see the symptoms of the problem. They recognize that they are experiencing the problem and that it is potentially harmful. They are ready to define and explore the problem. |

|

Critical |

"It is costing xxx dollars." Customers have a clear picture of the problem. They are ready to quantify its financial impact." |

|

Crisis |

"I must change!" Customers recognize that the cost of the problem is unacceptable and that they can no longer avoid change. They have reached the point at which the decision to change is made." |

When salespeople approach the sales process from a risk and change perspective, they deal directly, and in real time, with the critical change and risk issues that their customers must resolve. Instead of selling a rosy future, they focus on helping their customers identify the consequences of staying the same or not changing the negative present. When they help customers understand the risks of staying the same and specific financial costs or lost revenues related to staying the same, the decision to buy (change) takes on a compelling urgency. They are not dealing with an optional future but with the immediate reality of a problem that they must solve. Understanding and focusing on the customer's decision to change also give the salesperson a distinct advantage and a unique position in the marketplace.

Typically, there are two processes at work in a sale: (1) the customer's buying process, which is primarily designed to obtain the best (lowest) price, and (2) the vendor's selling process, which is designed to move products and services at the best (highest) price. These processes, with their conflicting agendas, naturally generate tension and mistrust.

When we work with the customer from the perspective of a decision to change, we set aside these conflicting agendas. Now both salesperson and customer work toward a mutual objective - understanding the customer's problem and aligning the best available solution so that the customer can make the highest quality decision about the proposed change.

-

The second focus of the most successful salespeople is on business development. That is, successful salespeople think more like business owners than like salespeople. We call it business think.

Suggesting to salespeople that they need to be concerned with the development of their customers' business brings obvious agreement. "Yes, of course," they say, "we do that." But the paradigm from which most operate becomes very clear when we ask them what happens after the customer agrees to buy. The typical answers include "coordinating the installation," "getting paid," and "training the customer." The interesting thing about these responses is that they are primarily focused on what happens to the salesperson. The business being developed is the salesperson's, not the customer's.

No matter how much lip service conventional salespeople pay to developing their customer's business, they are not fooling the customer. Today's customers are forcing vendors to take an active role in their business success. Tighter supply chain management and preferred supplier programs reward sellers who help develop their customers' businesses. Those who adhere to traditional sales practices are left out in the cold. Smart professionals know that focusing on the success of the customer will ultimately improve and enrich their own business.

When we ask the best salespeople what happens after the customer agrees to buy, they say, "We help them accomplish their business objective" or "The customer will realize x dollars in reduced costs or increased revenues." The business they are developing is their customer's business.

The point is that the answers to the question need to be a balance of items that happen to the customer's business as well as items that occur in the seller's business. Seldom do we hear comments on what happens in our customer's business.

Business think means that we take the time to understand the financial, qualitative, and competitive business drivers at work in our customers' companies. It means that we frame our communication with customers in terms that they understand and that matter to them. Finally, it means that when we have delivered our solutions, we measure and evaluate success from our customers' perspective.

Business think also has profound implications for how salespeople perceive themselves. When you approach your work as a business enterprise, you quickly realize that resources are limited and must be focused to achieve their greatest potential. You know that you can't be all things to all customers and devote your energy only to the best opportunities available. You come to respect your own time and expertise as valuable resources and expect your customers to do the same.

Successful salespeople do not waste time in situations where their solutions are not required. It is also why they tend to gravitate toward the opportunities where their services are most needed and highly valued.

We describe the behavior that results from this mindset as "going for the no." It is a mind-set that believes that at any given time, a small percentage of the marketplace will buy; therefore, we must quickly identify those that won't and set them aside for later attention. Compare this attitude to that of conventional salespeople who are taught to always be "going for the yes." They allocate their time equally among the entire universe of opportunities, and when they get in front of potential customers, they stay there until the customers disqualify them. They aren't treating their own time and expertise with respect, and it shouldn't come as much of a surprise when their customers don't either.

-

To succeed in enterprise sales, the most successful salespeople are interacting with their customers by building relationships based on professionalism, trust, and cooperation.

You could argue that all salespeople are working toward that same goal, but while that may be true in theory, it has not been translated into reality in the customer's world. In the mid-1990s, researchers asked almost 3,000 decision makers "What is the highest degree to which you trust any of the salespeople you bought from in the previous 24 months?" Only 4 percent of those surveyed said that they "completely" trusted the salespeople from whom they had bought. Nine percent said that they "substantially or generally" trusted the salesperson. Another 26 percent said they "somewhat or slightly" trusted the salesperson, and 61 percent said they trusted the salesperson "rarely or not at all." [1] Remember, these are the responses of customers about the salesperson from whom they decided to buy! What did the respondents think of the salespeople from whom they decided not to buy?

As we have already seen, this negative perception of salespeople is a problem inherent in the conventional sales process. Accordingly, the only sure way to break through the interpersonal barriers between salespeople and customers is to abandon conventional sales models. The most successful salespeople do not model typical sales behavior. The models that best reflect desired professional sales behavior are the doctor, the best friend, and the detective.

The Doctor

Doctors provide a model for professionalism that salespeople can relate to and emulate. Even though the medical profession today has its own image problems, let's consider it in a general sense - the medical profession at its best.

Doctors take an oath to "do no harm"; that is, do their best to leave patients in better condition than they find them. They accomplish this goal through the process of individual diagnosis. Picture a middle-age, overweight male walking into a doctor's office. Does the doctor observe the patient's appearance, note that he is a "qualified" candidate for a bypass, and recommend surgery? Of course not; it would be absurd. Doctors recognize that no medical solution is right for every patient and that they cannot diagnose patients en masse.

In contrast, salespeople regularly walk up to customers and prescribe solutions despite the fact that many of those customers may fit the profile only for the solutions in the most superficial way. The best salespeople, like doctors, diagnose each customer's condition individually and prescribe solutions that fit the unique circumstances of each case. Accordingly, their customers see them as professionals who are willing to take the time to understand their problems and can be trusted to offer solutions that not only "do no harm," but also improve the health of their businesses.

The Best Friend

When we say the best salespeople act like their customers' best friends, we don't mean that they get invited to backyard barbecues and family gatherings. Best friends are often our favorite companions, but they embody other qualities as well. Picture the most trusted person in your life - a spouse, parent, colleague, teacher, coach, or advisor. That is the relationship model we call the best friend model.

We expect our best friends to look out for our best interests. They help to protect us from errors in judgment. We also look to our best friends for honest opinions and answers. We trust them to tell us the truth. The best salespeople use the role of best friend as a litmus test. They ask themselves, "If this customer were my best friend, what would I advise in this situation?" When it comes time to offer solutions, they ask, "Is this the answer I would propose if this customer were my best friend? Do I have his best interests in mind or my own?"

The Detective

The third role that successful salespeople model is one of personal style and interpersonal process. In a television series, actor Peter Falk convincingly played Detective Columbo - an unusual kind of detective. He never threatened a suspect. In fact, he rarely even raised his voice. Columbo was mild-mannered and nonthreatening to the point of appearing ineffective. In fact, the show's criminals consistently underestimated this detective - at least in the early stages of the investigation. It was a natural mistake. Columbo made them feel safe and secure, and while they congratulated themselves on their craftiness, the detective quietly went about the business of diagnosing the situation and reconstructing the crime.

Amazingly, Columbo solved every crime he ever investigated (television series aren't exactly real life scenarios). He accomplished this feat in two ways: by observing the most minute details of the crime scene and by asking a seemingly endless number of polite, unassuming questions. By the way, Columbo's methods provide an excellent contrast to James Bond's. Bond, whom we examined in the last chapter, already knows all the answers, so he doesn't need to ask any questions. All that he needs to do is verbally challenge and strong-arm the villain.

As salespeople, we need to emulate the detective. We need to fully understand what is happening in our customer's world. We can accomplish this goal in the same non-confrontational way that Columbo solved crimes, through the power of observation and the process of questioning and clarifying the things that we see. In The Trusted Advisor (Free Press, 2000), David Maister devotes a full chapter to the effectiveness of the Columbo model. He also notes, the main barrier to using this effective model is our own emotional need to be the center of attention.

[1]The findings of the sales survey are recorded in, You're Working Too Hard to Make the Sale (Homewood, IL: Irwin, 1995), p. 16.

The topics covered herein concern solution sales, consultative sales, and consultative selling.

|

|