|

|

A Set of Skills for Enterprise Sales

The second element of any profession encompasses the skills and tools that its practitioners use to achieve their goals. Skills, as defined earlier, are the mental and physical ability to manipulate the tools that professionals use to execute systems.

In a enterprise sales process, the most successful salespeople are capable of using a large number of tools. Most of these are specific to certain elements of the sales process, and we discuss them in later chapters. Three major tools span the entire selling process and, as such, are best introduced before we describe the process itself.

These three tools help us answer one of the basic questions present in every enterprise sale: Who should be involved in decisions determining the problem, the design, and the implementation of the solution? What are the problems that the customer is actually experiencing? How are those problems impeding the customers' ability to accomplish their business objectives? How are those problems connected to the salesperson's solutions? How will successful business outcomes be achieved for the customer? The answers to these questions represent an equation we need to solve to successfully navigate a enterprise sale:

Right People - The Cast of Characters

It follows that if customers do not have a quality decision process, it is not likely they would assemble the best group of people to be involved in the decision. In the enterprise decision, the search for the elusive, single decision maker is futile. There is always the individual who can say no, even if everyone else says yes, and that same individual can say yes when everyone else is saying no. Reality shows that today's enterprise decisions are far more likely to evolve from a group initiative and consensus. Smart business executives realize that successful implementation is directly related to the degree of buy-in. This fact does not alleviate the need to find decision makers; it actually raises that task to a more sophisticated level.

One telling observation from the field is that when it comes to identifying and interacting with decision makers in a enterprise sale, the most successful salespeople don't take the hand that is dealt them. They don't accept the decision makers identified by their customers without question. Rather, they understand that customers who do not have a quality decision process in place are unlikely to be able to assemble an effective and efficient decision-making team. As a result, successful sales professionals take an active role in building the optimal "cast" for their customers. They seek to identify the important cast members in the customer's organization, involve each in the decision process, and ensure that each has all the assistance required to comprehend the problem, the opportunity, and the solution. Effectively managing the decision team is a job that spans the entire enterprise sales process. We call the tool used to achieve that task the cast of characters, and it helps us identify and access the right people.

The key to casting a enterprise sale is perspective. The cast of a enterprise sale needs to include a set of players that encompasses each of the perspectives required in a quality decision. In every sale, there are two major perspectives: The problem perspective includes members of the customer's organization who can help identify, understand, and communicate the details and cost of the problem. The solution perspective includes those who can help identify, understand, and communicate the appropriate design, investment, and measurement criteria of the solution.

Casting doesn't stop here. We also need decision team members who can bring the perspectives available at different levels of the organization to the table. For both the problem and the solution perspectives, we need to include individuals, internal and external, who represent and/or advise the executive, managerial, and operational levels of the customer's organization.

Why go through all this work? The obvious answer is that there is no other way to ensure that you are developing all of the information needed to guide your customer to a high-quality decision. There are also some less obvious answers. For instance, would you prefer to present a solution to a group that has had little or no input into its content, or would you rather present a solution proposal to a group that has already taken an active role in creating it? Would you prefer to deal with a newly installed decision maker who has replaced your single contact in the middle of the sales process, or would you rather face that new decision maker with the support of all the remaining cast members and with full documentation of the progress already made?

The answers to these questions are clear. The successful sales professional casts the enterprise sale to assemble the group of players who has the most impact, information, insight, and influence on the decision to buy. This shortens the sales cycle by effectively reaching the right people and helping them make high-quality decisions. You build predictability into your sales results and ultimately shorten the sales cycle time.

Right Questions - Diagnostic Questions

All salespeople are taught to use questions in the sales process, but most use questions in ineffective ways and in dubious pursuits. They ask questions to get their customers to volunteer information they have been taught is critical to the sale. Their goal is to identify who makes the decision to buy and to determine how much the customer is willing to spend on a solution. They want to maximize their contact with customers and get customers to pinpoint their own problems. All of these reasons subvert the most valuable use of questions - to diagnose.

The most successful salespeople are sophisticated diagnosticians. They understand that to effectively and accurately diagnose a customer's situation, they must be able to create a conversational flow designed to ask the right people the right questions. They also know that they gain more credibility through the questions they ask their customers than anything they can ever tell them.

The "right questions" refers to four types of diagnostic questions that salespeople use to understand and communicate customers' problems:

-

A to Z questions frame a customer process and then ask customers to pinpoint specific areas of concern within it.

-

Indicator questions uncover observable symptoms of problems.

-

Assumptive questions expand the customer's comprehension of the problem in nonthreatening ways.

-

Rule of Two questions help identify preferred alternatives or respond to negative issues by giving the customer permission to be honest, without fear of retribution from the salesperson.

These diagnostic questions, which we detail in the chapters that follow, are purposely designed to avoid turning conversations into interrogations, or rote interviews and surveys. Instead, they help salespeople develop integrated conversations, in which the customer's self-esteem is protected, mutual value is generated, and communication is stimulated. (Silence and listening skills, as we describe later, also play important ancillary roles in diagnostic questioning.)

Right Sequence - The Bridge to Change

Just as enterprise sales feature multiple decision makers, they also require multiple decisions. The content and sequencing of those decisions is what allows us to connect our customers and the problems they face to the solutions that we are offering. To accomplish this goal, we need to establish an ordered, repeatable sequence of questions that will lead to a high-quality decision.

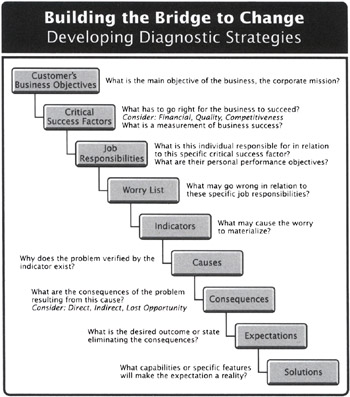

This sequence is called the bridge to change and is patterned after the methods physicians are taught to diagnose complicated medical conditions and prescribe appropriate solutions (see Figure 3.2). It guides salespeople by establishing a questioning flow capable of leading their customers through enterprise decisions. More importantly, it allows salespeople to pinpoint the areas in which they can construct value connections that will benefit their customers.

The bridge has nine main links; each is a potential area for creating and capturing value. It starts at the organizational level by examining the customer's major business objectives or drivers and the critical success factors (CSFs) that must be attained to achieve those objectives. It seeks to identify the individuals responsible for each CSF and to understand their personal performance objectives. The bridge prompts the salesperson to identify performance gaps by identifying potential shortfalls in the customer's key performance indicators, probing for their symptoms, uncovering their causes, and quantifying their consequences. In its last links, the bridge helps define the expectations and alternatives for solving the customer's problems and then narrows the search to a final solution.

The bridge to change functions like a decision tree. Each branch of the tree is integral to a quality decision. Each link logically connects to the next, and although we can travel several branches simultaneously, none can be skipped without disrupting the decision process and, of course, the potential sale. In fact, when you hear customer objections, what you are actually hearing is the direct result of a skipped or less-than-fully traveled branch. If each branch has been completed to a customer's satisfaction, all of their potential objections have, by definition, already been resolved. The customer can, of course, still refuse to buy, but it is unlikely that their refusal will be based on any reason within the salesperson's control.

The three tools - cast of characters, diagnostic questions, and the bridge to change - and the ability to consistently use them, represent the key skills of a diagnostic sales professional. They also represent the three components of the enterprise sales equation - right people, right questions, and right sequence.

The topics covered herein concern solution sales, consultative sales, and consultative selling.

|

|