Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 4: Leadership Communications Planning

Overview

The truth is it is almost impossible to kill a great brand, and marketers and agencies have to remember that. . . . The compulsion to change is often the wrong route. What they should do is accept who they are, and then express that in a meaningful and relevant way.

Shelly Lazarus

Conor Dignam, "Stormy Reign for Queen of the Blue-Chip Brands"

The new performance evaluation system was not going over well. In fact, the new appraisal process was met with outright hostility - if hallway conversations were any indication, most managers were refusing to use it at all. The director of human resources was beside herself. This new appraisal system, which was designed to be easier to use as well as more comprehensive and more equitable, seemed destined to be dead on arrival. Although the new system was designed to be used online and replace the old paper-and-pencil form, managers were very suspicious. Employees, who were encouraged to write self-appraisals and set forth new performance objectives, were leery, too. Their fear seemed to be twofold: first, lack of privacy, and second, how they were supposed to evaluate themselves. They feared that if they graded themselves too high, they might seem shallow, whereas if they graded themselves too low, they might get stuck with a poor review that would affect their compensation and their eligibility for promotion. As a result, the entire system, which cost $2 million to implement, was in danger of being written off. Worse, employee morale was sinking. Refrains of "Big Brother is watching" echoed in the hallways.

Unfortunately, this situation is all too common. Whether the subject is performance evaluations, new project guidelines, or new policies governing overtime, the underlying principle is the same: The new initiative represents change, and people do not like change unless it is explained properly and put into the context of the organization.

The reason for the failure of this new performance evaluation system was not the system itself. It was the way in which it was introduced - or, frankly, not introduced. While a huge investment was made in the development of the system, little or no attention was paid to communicating the system to managers and employees. Rather, it simply appeared, as if from on high. The HR director was so involved with developing the application and the benefits of using it that she and her leadership team simply forgot to introduce it properly.

With the benefit of hindsight, it is easy to throw stones and accuse the HR director of being myopic and not in touch with the reality of the situation, but the fact is that organizations often institute change initiatives, big and small, without so much as a second thought about communicating them. Leaders seem to assume that whatever they introduce will be accepted. Months later, when the initiative fails, they wonder why. They tend to blame the initiative itself, when all too often it was simply the failure to communicate it properly. As a result, a great deal of time, money, and good ideas is wasted. Worse, the whole cycle is repeated when organizations seek to refine or redesign an initiative that probably would be good, if only it were explained properly.

Leadership communications plays a vanguard role in communicating change as well as in reinforcing organizational culture. Planning communications in advance is essential to developing a leadership message that is consistent with the culture, finding ways to communicate change, and ensuring continued credibility. Noted commentator and consultant on change Rosabeth Moss Kanter places a heavy emphasis on the role that communications plays in keeping a culture unified as well as helping to keep it together during a transformational effort.

Active versus Passive Communications

Communications does not occur in a vacuum; it is part of the culture of an organization. As such, communications absorbs the character of the organization's culture. It is essential that those who actively create leadership messages be cognizant of those who passively receive those messages. Communications professionals need to be aware of what people are saying about products, people, and performance, both inside and outside the organization.

Active communications (what goes out) must reflect the reality of the world in which passive communications (what comes in) exists. Discordance between active and passive communications leads to an undermining of credibility; accordance ensures organizational alignment. Sensitivity to what's on people's minds is always important, but never more so than when communicating an initiative involving transformation. For this reason, leaders may need to prepare employees or customers for coming changes rather than springing the entire change initiative on them overnight with a single message. Leaders can introduce change with teaser messages prior to a major announcement, which may be given at an employee gathering or rally. Likewise, leaders need to follow up the message with a series of follow-on messages noting progress and keeping people up to date on what is happening.[1]

Assessing the Organizational Communications Climate

How do you find out what's going on within an organization? You ask people what's on their minds. As a leadership communicator, you need to discover the climate for communications. Climate refers to how open people feel about voicing their opinions or making suggestions. In places where the culture is repressive, many people are afraid to voice concerns even to coworkers, let alone to their boss. They also become distrustful of management because they feel that whatever anyone in management tells them is either untrue or bad news. By contrast, in nurturing cultures, people not only are open to one another, but feel free to make suggestions to their boss. Messages from the leaders are received with much more credence because people have learned to trust management.

Borrowing an approach from the social sciences, the best way to find out about the culture is to conduct a three-pronged study that uses interviews, focus groups, and surveys. Before embarking on any such study, you need to ensure the confidentiality of participants. Here's a sample disclaimer:

We are doing this interview (focus group, survey) to get your opinion about the climate of communications. We value your opinions and your ideas. We will also keep all comments confidential. Your comments and ideas will not be linked to your name.

Interviews

Interviews are best for getting to the heart of what people think about the organization. Individual interviews give you the opportunity to explore a question or issue with someone in more depth than is possible with any other method. A skilled interviewer can make the interviewee feel comfortable by assuring confidentiality, opening with small talk, and having an open and friendly demeanor. When people feel at ease, they will reveal a great deal about how they see themselves within the context of the team or the organization.

Sample questions might include:

Has your boss set clear expectations for your job? Why do you say that?

Do you know the objectives of your team/department? How do you know or not know?

Do you know where the organization is headed? How do you know this?

What is the climate for communications within your organization?

The other factor in this type of research is choosing whom to interview. Consider interviewing at least two people from every function or organizational level. In this way, you get a more balanced understanding of what individuals think and what they do within the organization.

Focus Groups

Focus groups are good for getting different viewpoints in a short period of time. You can use the interaction within the group to stimulate conversation as well as to bring differing points of view to the surface. Keep in mind that some people are shy in groups and are uncomfortable voicing their opinions, particularly when those opinions might be contrary to what the rest of the group thinks or what the organization fosters. Use an experienced facilitator to draw out the opinions of the group. Group dynamics will have a big impact on the quality of the responses and the nature of the discussion; you need someone who is experienced and skilled in managing these dynamics effectively. In a focus group, limit the time to no more than 2 hours.

Sample questions might include:

How do senior leaders communicate to you?

What kind of feedback do you receive from your boss?

Think of what people are saying about your organization. Do their views differ from those of senior leadership? In what way?

What happens when someone expresses an opinion that differs from that of his or her boss?

Surveys

When you want to take the pulse of an organization and find out the extent to which an attitude or belief is held across the organization, use a survey. The survey typically will ask between 10 and 20 questions. It can be done using a paper-and-pencil format, or it can be done using email or the Web. The format selected depends on the culture of your organization and how people use technology. Usually, the computer-based formats get a better return rate than hard copy.

It is best to send surveys to as many people as possible. If the company has more than 10,000 employees, however, sending the survey to everyone may be impractical or too costly. In this case, you may wish to limit the surveys to people within a particular function (e.g., marketing, sales, or purchasing) or at a particular management level (e.g., supervisors, middle managers, or senior managers). If you receive responses from more than 50 percent of those surveyed, and this number is at least 30 (and preferably 100 or more), you can consider your results valid. There will, of course, be some bias as a result of differences between those who do and do not respond, but the numbers of returned surveys should give you a good idea of the issues and concerns facing people in the department, function, or organization.

Furthermore, if you survey the entire organization, you can slice (organize) the data according to specific groups. Specific groups will often have more or less concern about particular issues; this is typically due to the nature of their jobs, but it is useful to know this when designing communications plans. For example, supervisors may need more communications on issues related to hiring, while middle managers may need greater levels of communications on development planning. The information gained from the surveys can help you plan accordingly.

Suggestion: Get some help from an expert in designing the survey. There is an art and a science to constructing the questions so that you get valid and reliable results that you can feel confident in using to make decisions. And there are techniques for distributing and collecting the survey that will increase the likelihood that you will get a sufficient number of surveys returned.

Communications Audits

Another form of survey used specifically for evaluating communications is the communications audit. While the audit may assess organizational climate, it is often used to measure the response to specific forms of communication, e.g., a video, a brochure, or a meeting. The purpose of the communications audit is to evaluate how well people understood the message and what they will do with the information they have received. For example, if you send out a video on changes to a benefits plan and follow up with a survey, you can ask whether people have the information they need in order to decide whether to make changes in their plan or keep it as it is, and whether they know where to go to seek further information.

Do you have to use all three methods of analysis? No, but the more types of analysis you use, the greater the validity of your conclusions. Also keep in mind that any one of these analysis methods is a form of intervention. And when you intervene, you must provide a context for it. For example, you must always explain why you are gathering data and what you will do with it.[2]

Leadership Communication Strategies

Once you know the issues facing an organization, you can plan your communication strategies. Communication strategies should echo the vision, mission, and business strategies of the organization. They should be telling people where the organization is headed, how it will get there, and what people need to do to make certain they are in alignment with the organization. The communication strategies are designed to

Develop and reinforce the bond of trust that must exist between leader and follower. Position the leader as one who can be trusted and is worthy of support. Winston Churchill and Rudy Giuliani were the right leaders at the right time when people in peril needed their guidance and leadership.

Affirm the organizational vision, mission, and values. Reinforce what the organization stands for and what people in it believe. Robert Redford founded Sundance Institute to support independent filmmaking, and he continues to actively support its mission through his actions and communications.

Facilitate a two-way flow of information throughout all levels of the organization, including manager to employee, employee to manager, and peer to peer. Enable communications to flow upward from follower to leader. Upward communications keeps the leader in touch with the people and enables people to have their voices heard, thereby promoting a shared stake in the enterprise. Rich Teerlink at Harley-Davidson emphasized open and honest communications as the means of effecting lasting, positive change.

Create the impetus for organizational effectiveness (e.g., making things happen). Tell people what is happening now, what will happen next, and what will happen as a result of their actions. Steve Jobs lets people at Apple know why they should care about their work and gets them excited about the difference they are making in the world of design and technology.

Drive results. Achieve what the organization is supposed to do: Make great products, deliver terrific service, improve people's lives, and so on. Jack Welch was a master at pushing the organization to achieve its stated goals, and he used his communications to prioritize the importance of making the numbers.

The other part of the leadership communications equation is giving people reasons to want to embrace the strategy. You develop your messages as reasons for people to support the strategy. Keep in mind that there is a natural overlap between purpose (as described in Chapter 1) and strategy; in some cases they are one and the same. Strategies and supporting messages echo one another to support organizational goals.

Four Leadership Communication Channels

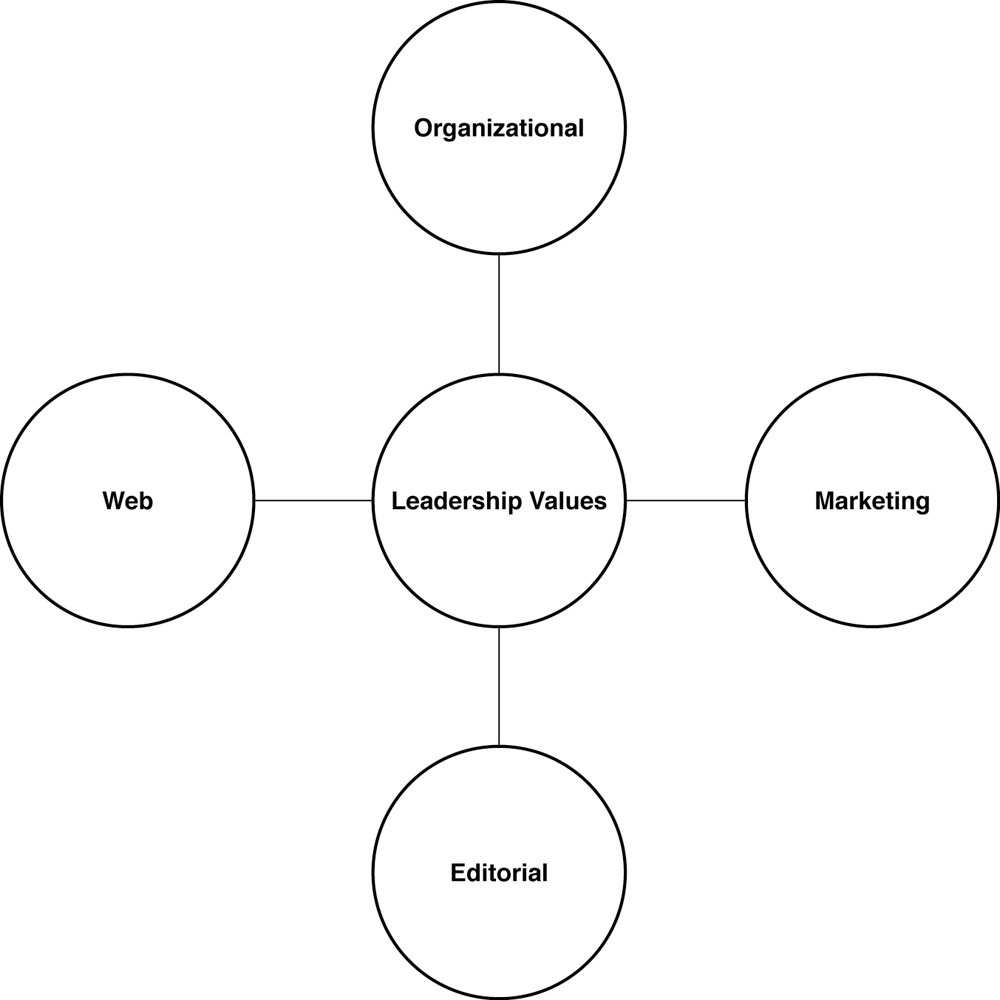

Just as individuals use different forms of communications - words, gestures, signals of attentiveness - organizations use various communication channels. Typically an organization utilizes four types of communications, or channels (see Figure 4-1). While it may be advantageous to use all four channels to communicate a single initiative, it is often feasible to select a single channel for a particular message.

Organizational communications refers to the ways in which individuals, teams, and the entire organization communicate one to one, group to group, or organizationwide. There are no hard and fast rules about what is and what is not "organizational communications," but think of it this way: It is the way messages are disseminated throughout an organization.

Organizational communications can be as simple as a single email, or as complex as a media campaign regarding transformation. No single entity has ownership of organizational communications; it belongs to everyone. Why? Because communicating with others is each person's responsibility.

Editorial communications refers to messages designed to elicit endorsement from a third party, typically the media and by extension the public at large. Public relations departments send out media releases to describe what is going on inside an organization; these releases may cover new products and services or discuss internal developments related to people and programs. By and large, these releases convey a single point of view that is favorable to the company. These forms of communications are designed to be used by external media (broadcasters, periodicals, newspapers, trade publications) to develop their stories, which the organization hopes will be both informative and positive.

Many large organizations also have in-house communication channels involving the development of articles for the organization's newsletter or web site. You can also consider a speech or a guest op-ed column by a company CEO as another form of editorial communications. In this instance, there is little filter between the leader and the public, since the leader's opinion is communicated directly, without benefit of interpretation by a reporter.

Marketing communications refers to communications designed to present a point of view, e.g., to sell or promote. Think of advertising. What you see in a 30-second television spot, Facebook ad, or a four-color print ad communicates a message that is paid for by the organization. The same technique can be adopted by organizations that wish to sell the benefits of organizational transformation.

Marketing communications is especially effective for communicating a sense of urgency. You can structure the message so that you concentrate on the WIFM (what's in it for me?) as a means of persuading people that the change, the program, or the initiative is good for them as individuals and for the entire company.

Web communications are communications that reside on the web site. These messages may be developed solely as e-messages, or they may be retreads of articles, videos, and other media.

The Web itself, however, can be a very powerful tool for enabling a leader to speak directly to his or her people. There are two popular methods. One is a webcast, which is a video telecast of a presentation or a conversation that is transmitted over the Web and restricted to subscribers, e.g., employees, dealers, media, or other groups. The other is a webchat, which enables a leader to respond to questions submitted via email. Sometimes the reply is sent out audio only or as a text message. Both methods are very direct means of getting to key issues. In addition, they can be replayed at the Web user's convenience or archived on the web site for later reference.

Determining the Right Media for the Right Communication Channel

Selecting the appropriate communication channel for a message is often as important as the message itself. The channel, which can be anything from an email to a speech to the masses, must be evaluated for its ability to convey the gravity of the message with the appropriate intimacy and leadership value. (Note: Channel refers to the method of communication (e.g., organizational, editorial, marketing, or Web); media refers to the vehicle (e.g., video, brochure, news article, or banner).

You can use just about any media in your communications channel - video, print, collateral, and so on. It is a common mistake to assume that video is only for marketing communications (e.g., a TV spot) and print is only for editorial. The truth is that you can use either or both - as well as other forms of media - for any channel that you like. The media you select are dependent upon the message. (Budget, too, plays a great role. Video can be expensive, as can four-color brochures.)

What kind of media you choose depends upon the importance of the message. All leadership messages have importance, of course, but some are more significant than others. Here are some suggestions you might consider:

Video affords the leader the opportunity to speak directly to an audience and to augment the message with stories and visuals that underscore key points. For example, if the issue is the adoption of a new strategic plan, the leader may invite different people from throughout the organization to comment on their hopes and expectations, or to say what they will do to change the organization and carry out the plan. Additionally, the leader and his or her team can comment on what the new company will look like once the plan has been achieved.

An all-employee meeting provides the opportunity to introduce the leadership message live in front of the entire organization. The leader needs to take a front and center role; she or he should explain the reason for the transformation, be it a new strategic plan or a new direction for the company. The leader may also wish to invite members of the leadership team to be on stage with her or him. It may even be appropriate for one or more of them to speak, to explicate the issue from their point of view. The meeting may conclude with a call to action, asking people to commit to the new idea. It should invite input and contributions from everyone.

Team meetings can flesh out concepts introduced at the all-employee meeting. They can translate the broad vision into departmental and team objectives, i.e., what the team will do to carry out the mission, vision, and values. In other words, small meetings are where teams and individuals take ownership and make it happen. If they do not do so, the vision or the plan remains the property of the leader, and nothing gets done. Team meetings should allow for plenty of discussion. Ownership of an idea cannot be imposed; people have to warm up to the idea and talk about it first.

One-on-one meetings are a team leader's opportunity to reiterate expectations and bring the leader's message to a personal level. The team leader should solicit the employee's opinion and conclude with a personal call to action, asking the employee to state what he or she will do to ensure the success of the initiative or plan. (Later in the chapter we will further explore ensuring feedback.)

Webcasts are ideal for enabling the leader to speak live directly to the audience in a way that cuts through the clutter. The video image will be viewed on an employee's computer, so the setting will be intimate and direct. Think of the message as the leader's opportunity to speak one-on-one with everyone in the organization. Keep it short; less than 10 minutes is ideal if a single person is speaking. (Note: Many organizations run their important videos as webcasts, but in doing so you lose some of the intimacy of a leader speaking live.)

Print media formalize the message; they may include a brochure, a poster, or a wallet-size card. Many organizations print their vision, mission, and values on wallet-sized cards so that all employees have them. Other organizations take a more elaborate approach. Some companies have turned their vision and mission statements into drawings and printed them as posters. Many times the art is done by the employees themselves, adding an element of ownership to the process. There are other approaches. Kellogg's, for example, produced a four-color brochure delineating the company's vision, mission, and values for the sales team as well as expectations for sales performance.

Media releases are designed to get the attention of the media: television, radio, newspapers, and the trade press. Use them to communicate important issues to the public or to the trade. Follow up with individual reporters to elaborate on these releases to ensure that your message is getting through. Keep in mind, however, that reporters are not publicity agents. They are seeking good stories that present all sides of an issue. If you maintain good relations with the media, you have a better chance of getting your story told. These relationships will play out especially well when the organization is going through a transformation, especially with senior leadership changes.

Banners get attention and serve as reminders of the message. Post them in the cafeteria or in main traffic hallways. When you visit a military base, you will often see a banner with a slogan hanging from a key work area, such as an airplane hangar or tank garage. Peek inside a football team's locker room and you will find a banner with the team's slogan for the year hanging in a prominent place.

Email works well for the reiteration of key leadership messages and announcements on progress toward milestones. Email may also be used for alerts, letting people know that an event (such as an employee meeting) is about to occur. Be selective. Most people receive far too much email already. Choose your moments wisely; otherwise the message will be ignored. (For more on email, see Chapter 5)

Broadcast voicemail is a method a leader can use to get the message out. You can use voicemail the same way as email, but it has one further advantage - the personal touch. Voicemail conveys the tone and personality of the speaker. And as with email, keep all voicemail messages succinct and to the point. Otherwise the message will be erased.

Integrated Communications Planning

Of course, for maximum impact, it may be appropriate to use two, three, or all of these media. If the gravity of the message is weighty, it deserves multiple channels and multiple forms of media. Leaders need to plan how their messages will be disseminated. We call this planning integrated communications - multiple channels and multiple media working together. The virtues of integrated communications are threefold: One, you can design a message to work in different ways for different media; two, you increase the chances of the message's being seen and heard; and three, you can use the media to keep the message fresh and alive - and therefore of greater interest.

A good example of integrated communications is the launching of a new vehicle. Commercials appear on television and radio. Ads show up in magazines, in newspapers, and on billboards. And the vehicles appear in dealer showrooms. Likewise, companies that want to communicate key issues may convene an all-employee meeting, send letters to employees' homes, and post banners in employee cafeterias. In both instances, the organizations are integrating channels and media to ensure exposure to the message.

Frequency

Once is rarely enough; repeat, repeat, repeat is typically the rule. The gravity of the message dictates the amount of repetition. It is important to repeat the message frequently and in new and different ways. Varying the media used can assist in this effort. Use video for one announcement. Choose a meeting for a reiteration of the message. Post banners for thematic tie-ins. And use email to reinforce key points. In this way, the recipient receives the message in a variety of different ways over a period of time.

A word about budget: Video and print can be expensive, but in-house production facilities can reduce the cost. Furthermore, you can use other forms of media, like articles and webcasts, to carry the bulk of the message and be selective with more expensive media.

Reaching the Right Audience

The content and delivery of the leadership message are dependent upon the audience's needs and expectations. Just as advertisers target their messages to specific demographic groups, e.g., young males 18 to 24 or women 21 to 48, leaders can target theirs to specific interest groups, e.g., managers, employees, customers, or suppliers. The heart of the message will remain consistent, but the point of view may differ. For example, a message to employees about a new product launch will describe both the product and the support the employees must deliver to the customers. A product launch message to a customer will concentrate on features and benefits and describe the support the customer will receive.

In shaping the message, consider these points:

Select the key influencers. Consider whom you want to reach first - those who can influence your message in a positive way. It may be appropriate to invite key members of the media for a preview of a new product or an inside look at an organizational initiative. This is a tried and true technique in public affairs circles as a means of creating buzz, i.e., excitement. At the same time, consider those who can adversely affect your message. It is appropriate to give them an inside briefing, too, so that you can address any potential negatives and defuse any negative reactions prior to general release of the message.

Target the message. Adjust the content of the message to the audience you wish to reach. Sometimes the same message will be appropriate for all employees at all levels of the organization, and in this case everyone will receive the same content. It is often a good idea, however, to alert senior management to the message and even send them a prerelease message along with suggestions as to what kind of reaction they should expect from their people when the message is delivered. In this way, you gain buy-in of the leadership message and create a greater sense of shared destiny. All of us, no matter who we are, appreciate inside information because it makes us feel special and more in the know.

Reiteration is good. People need to hear the message over and over again - once is not enough. Just as you repeat messages with different media, you repeat messages to the same audiences. You can tweak the content to keep it fresh, but it is essential for the leader to repeat the core themes over and over again. Repetition does two things: It increases the likelihood of retention, and it demonstrates importance. In particular, reiteration of a message underscores a leader's consistency, which leads directly to credibility.

Keep the big picture in mind. Targeting and audience selection are important, but it is also important that you keep the whole story in front of you. It is essential that you make certain that everyone is getting the same big picture message. The leader must ask him- or herself periodically whether key constituents have the information they need in order to do their jobs and have confidence in the leadership of the organization. People do not need - nor do they want - to know everything about everything. But they do need to feel that the communications they are receiving is accurate, honest, and truthful. If it is helping to strengthen the bond of trust between leader and follower as well as to drive results, then the communications is appropriate.

Timing Is Everything

Once you have selected the right media, choose the right time to make an announcement. The most dramatic example of timing occurred in the immediate wake of September 11. Anything unrelated to the events of the day, including meetings, conferences, and advertising, was cancelled. While an event of this magnitude is thankfully a rarity, communicators need to be aware of events both inside and outside the organization. You want to strive for people's maximum attention. This is much easier said than done. During times of crisis, announcements of management changes or responses to the crisis are very appropriate. But when you are announcing a new initiative, don't do it during the holidays, when people are thinking of family and social obligations.

Making the Message Resonate

When it comes to ensuring that a message is seen and heard by the right people, leaders can learn from public relations professionals. In his book Feeding the Media Beast, Mark Mathis identifies a number of techniques that individuals or organizations that are seeking publicity employ to get noticed by the media. Three salient elements of raising awareness are relevant to leadership communications: difference, emotion, and simplicity.[3] Let's take them one by one.

Difference. Leaders are about making a difference. We look to our leaders to give us the guidance to take us to places where we have not yet gone. Therefore, leaders need to link their communications to their difference. A leader's difference is both metaphorical and literal. The metaphorical difference relates to the difference the leader will bring to an organization: how he or she will make changes that will make things better for the stakeholders. Colin Powell is a master at delivering a message that explicates a policy and demonstrates the benefits. The second difference is literal. The leader must look to make her or his messages different (i.e., "fresh").[4] The freshness may emerge from the use of new and different words or stories to underscore key points or from the use of different forms of delivery. Former Speaker of the House Tip O'Neill was a master of the well-honed story; he had a treasure trove of tales that he was ready to tell at the right moment. Likewise, politicians on the campaign trail are good at finding new locales and venues for their messages; one day it might be a school, another day a factory, a third day a farm. By linking location to constituency need, they illustrate their vital difference as well as keeping the message fresh and alive.

Emotion. All of us are bombarded by messages, both spontaneous and recorded, all day long. Most of the time the words and sounds run together. We stop in our tracks, however, when we sense emotion - or, better, passion. Former Governor of Pennsylvania, Mark Schweitzer demonstrated passion as he addressed the media hour after hour during the Somerset mine disaster in the summer of 2002. When the miners were found alive and rescued, his passion turned to getting to the root cause of the disaster and determining how such disasters might be prevented in the future. Passion need not be oratory. Mother Teresa was a quiet, unassuming speaker, but her words echoed her passion for her mission of providing for the neglected poor.

Simplicity. People have a lot on their plate. A leader needs to shape the message in a way that is straightforward and simple in order to make it accessible. Remember the KISS slogan (Keep It Simple, Stupid). Bill Clinton's first presidential election campaign adapted this phrase to "It's the Economy, Stupid" to remind everyone on the staff what the real issue was; it worked, and Clinton defeated an incumbent president. (Do not think that sloganeering is beneath you. It simply gives people a handle with which to grasp your message and begin to understand it.)

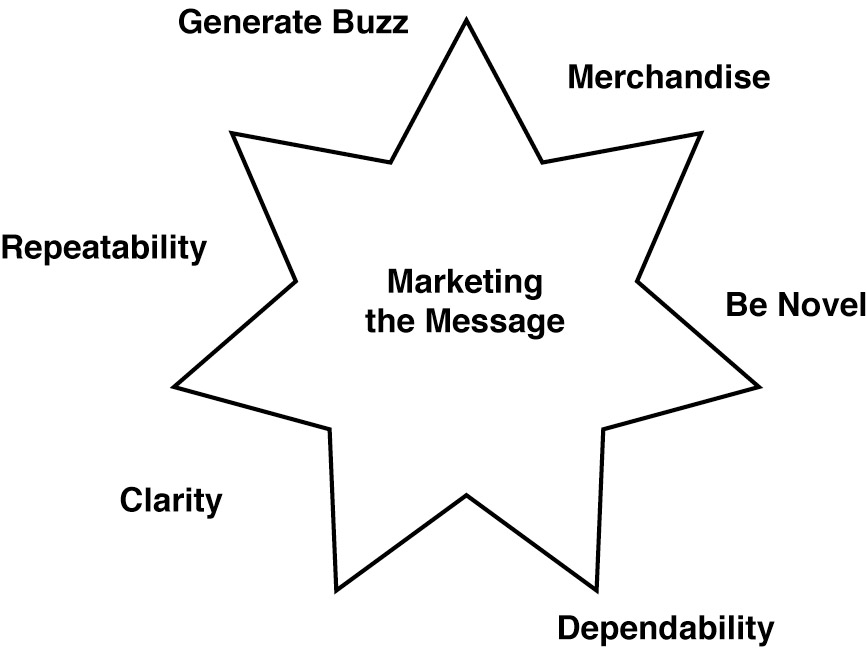

Marketing the Message

Advertisers also know how to make certain that a message resonates. Their job is to create awareness and provide a stimulus for action. Here are some things to consider (see Figure 4-2):

Generate buzz. Get people talking about what you are saying. Take your cue from the Star Wars marketing team; they begin marketing the next sequel along with the current release, often years in advance of its premiere showing. Come opening day, you cannot pick up a newspaper or magazine without reading something about the phenomenon. Much of the promotion is free media. Leaders need to get people talking about their messages, too. Select key influencers the way a marketer might select key media outlets or talk show hosts. Grant them access to what's going on and challenge them to spread the word.

Merchandise the message. Give people something in return. Consider Bill Veeck, the legendary baseball promoter; his promotional concepts sprang from his love of the game as well as his respect for the paying customer.[5] Leaders need to do the same. Logos on hats, slogans on polo shirts, and banners in the hallways will get people exposed to the message. If you use the message as the theme of a sweepstakes and create some genuine excitement, people will get caught up not only in the fun, but in the meaning of the message.

Be novel. Look for ways to make the message new and different. Advertisers do this by being creative. The U.S. Army introduced a high-end action adventure PC-based game entitled Action Army with two aims in mind: one, to attract potential recruits and get them to consider enlisting, and two, to demonstrate new forms of military tactics. Not only is this approach creative, it enables participants to experience the Army for themselves.

Dependability. Be seen as a relentless communicator. Get people used to seeing you articulate the message over and over again. Budweiser sponsors major sports because this gives it the optimum opportunity to reach its core market. Leaders must also find multiple ways to disseminate their messages - email, web site, video, telephone, and, yes, in person. When you become dependable, people will look to you for information as well as for inspiration.

Clarity. Keep the message consistent with the culture of the organization. Volunteer-based organizations such as the Girl Scouts, the Salvation Army, and the U.S. Marine Corps excel at making their messages simple, direct, and in keeping with their cultural values. When you see an ad for one of these organizations, you know what the organization stands for; there is no ambiguity about its purpose or intention.

Repeatability. It is overly optimistic (and maybe a little presumptuous) to think that people will remember a message the first time they hear it. Maybe the listener didn't hear it the first time, or perhaps it was not relevant to her or him the first time she or he heard it. It is the leader's responsibility to repeat the same message in different locations. The more times an audience sees and hears a message, the greater the chance that they will remember it. Think of advertising for your friendly local auto dealer. You see new ads for the business on television, on the internet, or on billboards. Pretty soon you get the point of who the dealer is and what he sells. Leaders, too, need to be seen and heard frequently.

Ensuring Organizational Feedback

Effective communications is a two-way street. All too often leaders spend the bulk of their time on crafting a message without stopping to listen to what people are saying about it. It is imperative that leaders provide avenues through which followers can voice their opinion of a leadership message as well as provide additional ideas that reinforce organizational values.

In this way, as mentioned previously, leaders enable the employees to take ownership of the idea. When you ask for feedback, you are saying, "We care about you, and we want your ideas." In return, the employee will feel a sense of obligation to contribute. In effect, asking for feedback is a kind of call to action.

The U.S. Army has a policy of expecting junior officers to challenge senior officers' opinions on matters related to the health and safety of the troops. During After Action Reports, the postmortem reviews of military exercises or actions, junior officers are encouraged to speak up and say how things might have gone differently. Why? Because the Army views AARs as learning tools. Continuous improvement will occur only when people can speak their minds. This does not mean that senior leaders need to agree; it simply means that they must listen. The same rule should apply in the civilian sector.

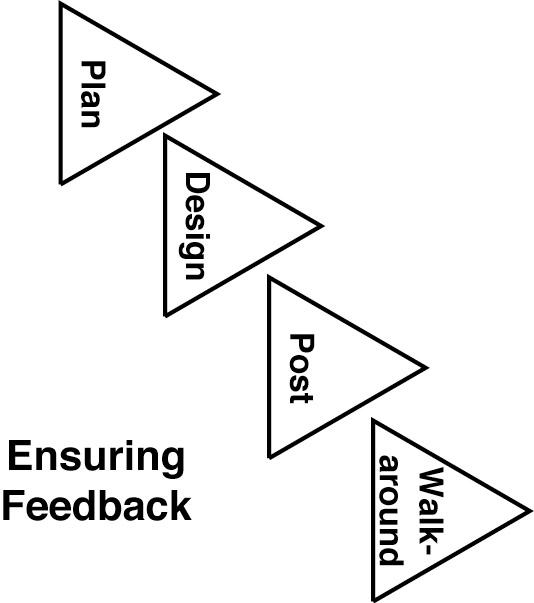

Implementing a Plan for Soliciting Feedback

Leaders need to understand that feedback will happen spontaneously. It is part of the passive communications environment discussed earlier in the chapter. People will respond to the message in any number of ways: discussing it with colleagues, talking to their friends about it, or sometimes speaking to the media (off the record, of course). What the leader needs to do is to ensure an outlet for the feedback. You can do this in several different ways (see Figure 4-3).

Plan for feedback. When you develop the communications plan, build a feedback loop into the process. As part of the planning process, let people in the organization know that you will be soliciting feedback and sharing the results of that feedback with them.

Design a meeting around feedback. Encourage team leaders to hold feedback meetings. The only action item for such a meeting will be discussion of the issues. You can even provide a "meeting in a box" toolkit with questions to help managers who are unfamiliar with the feedback process to get employees to talk about the issues.

Post the feedback you get on your web site. Select sample electronic survey feedback and emails and post them on your web site. Omit the names of respondents; this protects the respondents' confidentiality as well as keeping people from focusing on the personality rather than the expression of the idea.

"Walk around" to get feedback. Get out from behind the desk and walk the halls. Find out what people are thinking. A great way for leaders to do this is to make a habit of dining in the cafeteria at least once a week.

Ensuring that Feedback Is Heard

Many leaders say that they want feedback and even ask for it; the problem is that they never seem to find the time to respond to it. And let's be fair, leaders have many to-dos. The leader of an organization with hundreds or thousands of employees cannot be expected to respond to every email. What he or she can do is assign people to screen the mail and provide some response, and also respond personally to certain messages.

Another good tactic is to hold a webchat, which is an online question-and-answer session between leader and employees over a secure Internet connection. One way to begin the session is to have the leader sum up what he or she has heard so far and then open the session to questions from employees. (Hint: It never hurts to prepare a few questions in advance in case respondents are slow in submitting questions.)

Yes, Bad News Here

Leadership brings with it isolation. As a leader moves higher up in an organization, he or she loses touch with the people at the grassroots level. Ensuring that feedback channels are kept open helps the boss stay in touch. But leaders need to do more. They need to establish ground rules that say that it's okay to deliver "bad news." Enron is a classic example of a company where the delivery of bad news was punished; people who asked probing questions, questioned decision making, or reported bad news were not promoted, and in some cases were asked to leave the company.[8] Enron is not an isolated example. Many companies do this, and in the process they isolate their leaders from the truth. Leaders themselves can make it clear that they want the unvarnished facts. Abraham Lincoln was constantly nagging his generals to give him the truth, especially when the Union was losing. Successful business leaders do the same.

Let's face it, isolation at the top is often the leader's own fault. He or she fails to meet and mingle with front-line supervisors or talk to customers. Worse, the leader promotes those who tell him or her what a good job he or she is doing and are always ready with the positive spin. Some leaders shun candid speakers because they fear that listening to them will reflect poorly on their leadership. In fact, the opposite is often the case. When small problems go unnoticed and untreated, they can mushroom into huge issues, even catastrophes. Colin Powell has said that if a leader is not hearing bad news, something is wrong. "The day soldiers stop bringing you their problems is the day you have stopped leading them. They have either lost confidence that you can help them or concluded that you do not care. Either case is a failure of leadership."[9]

The Challenger disaster is one such example. The engineers at Morton-Thiokol knew that the O-rings in the booster rockets were not certified to withstand freezing temperatures. Yet when NASA pushed for a launch in near-freezing weather, the engineers had no ready way to communicate their knowledge. The "no bad news" culture that permeated the space program at that time thwarted open dialogue between the suppliers' engineers and program leadership. All the engineers could do at launch time was watch in helpless agony as the Challenger's booster exploded in midair. In contrast, years earlier, Gene Kranz, the legendary flight control director of the moon flights, was in the room when Apollo 13 suffered an oxygen tank rupture en route to a lunar orbit. The astronauts in the spacecraft, together with the innovative flight team on the ground, devised a solution that brought the astronauts home safely. This culture of cooperation is an example of Kranz's leadership style; leaders and doers operated in an environment where information was shared openly.

Getting Feedback One-to-One

Getting honest feedback from direct reports is no easy task. We humans have a strong instinct for self-preservation, so we don't bite the hand that feeds us. Therefore, when the boss asks us what we think of something coming from the top of the organization, our first reaction is to be positive. We don't want to say anything that will put our careers in jeopardy. Such a reaction may be human, but it is not healthy. We owe it to our leaders to give them honest feedback, but our leaders need to set the ground rules - i.e., they need to ensure that what is said to the leader will be kept in confidence and will not be used against the employee.

So how do leaders get feedback? First, they need to put people at ease. Make it clear that candor is the operative process. Demonstrate the benefits of honesty by accepting feedback in the spirit in which it was delivered. Next, leaders need to ask for feedback on a regular basis. You want to get people in the habit of expressing their ideas. No leader should expect to get instant candor, but when someone speaks out and does not suffer for it, others will begin to do likewise and may be more forthcoming. Still, the leader needs to work at getting feedback. Often what is not said may be the most revealing truth of all.

Of course, we need to separate the deliverer of bad news from the creator of the bad news. When people make a mistake, there will be consequences. Reporting the bad news, even when it involves your mistake, is a form of leadership; it's called taking responsibility for one's own actions. Merely reporting that news, however, should not reflect negatively on the messenger, if it's delivered in a way that is intended to keep the boss informed so that she or he has the information needed to take corrective actions. Leaders do not want to create a culture of tattletales; rather, they want to create a culture in which people can speak openly and share information in ways that reflect the credibility of the information and the organization.

The Benefits of Leadership Communications Planning

Improved credibility results from strong and effective leadership communications planning. The benefits include increased levels of trust, improved alignment throughout all levels, better two-way communications, and the achievement of lasting results - all of which are a direct outcome of the strategies mentioned earlier in the chapter.

The planning process underscores the fact that everyone in the organization has a role to play in communications. The leader is the chief communicator, of course, but he or she should not be expected to shoulder the communications load alone. The leader should enlist the support of the leadership team as well as professional communicators. Furthermore, if the message is to be effective, everyone in the organization has to hear it. In addition, those at the top of the organization need to know what people are saying about the message. Communications is integral to an organization, and in the communications process you see just how important a role it plays in instilling the organization's vision, mission, and values.

Note: Surveys of organizational culture are another effective way to determine the communications climate. These surveys are designed to measure attitudes as well as business practices, customer service, operational focus, and mission, vision, and values. From these you can discern the communications climate. One of the best surveys of its kind is the Denison Organizational Culture Survey, which specializes in linking performance to bottom-line results.

Shelly Lazarus - A Brand of Leadership

She was young, pregnant, and working late. The man whose name was on the door of the firm for which she worked walked into her office. "He asked, ‘Are you alright?'" then sat down and started to talk. . . . He did so every night [at six], on the dot, for the next month until I gave birth. We became great friends." He was David Ogilvy, legendary ad man, and she was Shelly Lazarus, just beginning her career in advertising.

Years later, Lazarus became CEO of the agency. Now called Ogilvy & Mather Worldwide, the firm has offices in over 100 countries and billings in excess of $13 billion. It has handled some of the bluest of the blue-chip brands, including American Express, AT&T Wireless, Coca-Cola, IBM, Ford, and Kodak. Lazarus was also a member of the board of General Electric. She has cultivated her own brand of leadership, one that is consistent with her own values as well as with the values she gained from her agency, including David Ogilvy. According to Lazarus, women have gone from "reaching for the engagement ring to reaching for the brass ring." While she "crashed through the glass ceiling," her path was not without its obstacles; in particular, she recalls being told that jobs were not something to "waste . . . on a woman." Still, Lazarus was prepared. She was a graduate of Smith College and held an M.B.A. from Columbia. When Lazarus tells her story today, she is reminding young women of their collective past as a means of educating them about their future opportunities, a classic model of leadership communications.

Champion of Advertising

In an age when advertising agencies are bought and sold like commodities, O&M remains distinctive. As part of the huge WPP communications family, O&M has retained a unique identity as the agency of brands: identity, image, inspiration, and aspiration. At O&M they call it 360 Degree Brand Stewardship, touching all the points where the consumer meets the product or service - on the shelf, in a commercial, in a print ad, using the product, or dreaming of the product. "Once the enterprise understands what the brand is all about, it gives direction to the whole enterprise."[14] The responsibility for ensuring brand consistency falls on employees. "They are absolutely critical. If the people who work in a company don't understand what the brand is, if they can't articulate what the brand's all about, then who can?"[15]

At the same, Lazarus believes that you have to make the communications genuine. "People don't like being given messages," says Lazarus, "but they love listening to stories. I encounter fresh new examples every day of the principles I consider important. I find them at work, in my everyday life, in the media, and anecdotally. When I communicate principles using fresh, real life examples, stories that tell a tale, people always ‘get it' that much better."

Her ability to be articulate has made Shelly Lazarus one of the most quoted advertising executives, not simply because of her gender but because of her insights. "Consider the value an ad agency brings. We help build brands, and a brand is the most critical asset a company has today. Sure, we're under more scrutiny from clients, but accountability means credibility."[16] Lazarus believes that an ad agency is really a "business partner" that is responsible for helping to grow the client's business. Toward that end, Lazarus would like to see the agency become a partner that can help to integrate advertising, marketing, and internal communications.[17]

The business of advertising is cyclical. Lazarus's belief in its power to influence is not. "The ad industry isn't struggling for a new set of principles or abandoning the ones that made it great from the start."[18] Despite downturns, Lazarus says, "I'm having more fun than at any other moment in my 30-year advertising career. The game is more interesting and more relevant than ever."[19] In 2001, O&M won more than $700 million in new billings. That same year, Advertising Age, the industry's top trade magazine, recognized O&M as "the outstanding American agency."[20]

Integration of Work and Life

Lazarus has mingled her personal and professional lives in a way that makes her a role model. She and her husband, George, a pediatrician, both hold demanding jobs, but they make time for their three children, including finding time for skiing together. Her kids "insist that I ski alongside them without my mobile phone."[21] When her children were younger, she took them to visit David Ogilvy in the south of France. "Seeing him play with my children made me realize how completely intertwined my career and family have become."[22]

Lazarus has come to an understanding of herself as a role model. Fortune magazine has included her in every issue of its annual "50 Most Powerful Women in American Business." Her example of making time for school functions "gives other women in the company, or clients, the confidence to be able to say, ‘I'm going too.'"[23] Young women seek her out for advice. "There's one thing I say all the time: You have to love what you're doing in your professional life. If you ever want to find balance, you have to love your work, because you're going to love your children."[24] Most important, Lazarus believes in the direct approach to integrating work and life. "Encourage them, outright, to follow your example."

Her boss, Martin Sorrell, chairman of the WPP group (of which O&M is a member), says, "She has an incredible focus on people and understanding of this business and the way it is developing. But I wouldn't want [to say] she's just a great people person; she is a very good business manager who doesn't back away from tough decisions."[25]

Saying It Once Is Not Enough

Lazarus places great emphasis on reiteration. "I don't think you can ever communicate too much. Communicating to your organization is not something taken care of a couple of times a year in memos, or at the annual Christmas party speech. I know from my advertising background that the most effective communication is multilayered. One message builds on others."

As an advertiser, Lazarus understands the value of different forms of communications. "Emails are great for speed, but they never replace the face-to-face. Group meetings are fine for the camaraderie, but they never replace the intimacy of one-to-one. Formal communication - the written word - gives weight, but all the more so when it is supported by spontaneous and informal contact."

"Above all, you can never walk the halls too much," she says. "David Ogilvy once told me that as much time as he spent on people, it was never enough. Since people are the number one asset of any organization, I don't think you can ever spend too much time with them - in written communication, on the phone, in person."

Sustaining Merit

Lazarus credits David Ogilvy with creating a sustainable foundation for the business. "[Ogilvy's] genius was in taking a very strong point of view about how to run an organization and from that point of view developing a set of principles . . . that have actually lived on in our people."[26] Lazarus believes that Ogilvy's befriending of her as a young pregnant woman stemmed not only from his sense of "democracy" but also from its being another way of "challenging the status quo."[27]

By telling and retelling her story and the story of her relationship with Ogilvy, Lazarus is building upon the virtues of the past as a means of creating the future - of growing the organizational brand, so to speak. Her stories remind others of the evolution of professional women as well as the opening of new doors of possibility for both men and women. As Ogilvy did, Lazarus, too, values a "meritocracy." People remain at O&M because they contribute. "[Ours] is a non-political culture. . . . It's an organization that holds its people accountable."[28]

Accountability is essential to leadership, and through her words and example, Shelly Lazarus, brand leader, demonstrates what it takes to lead by developing others and challenging them to find their own paths. Her stories provide illumination for others who are seeking to create their own way or to add luster to their own brands.