Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 10: Coaching - One-to-One Leadership Communication

Overview

[T]he new leadership is in sacrifice, it is in self-denial, it is in love and loyalty, it is in fearlessness, it is in humility, and it is in the perfectly disciplined will. This . . . is the distinction between great and little men.

Vince Lombardi

David Maraniss, When Pride Still Mattered: A Life of Vince Lombardi , p. 406.As a young teacher I learned never to promise anyone instant success. Instant success does come for some gifted pupils, but for the average pupils, success is a journey of testing their intention.

Harvey Penick

Harvey Penick with Bud Shrake, The Game for a Lifetime, p. 115.

The young caddie was a constant complainer; nothing was ever as it should be. Everyone else had it better than he did. Things always seemed to go against him. The young man's complaints were so frequent that he was known among his fellow caddies as Willie the Weeper. Things came to a breaking point when, while he was out hitting golf balls, he broke the hickory shaft of his club. Willie began wailing. Tom Penick, head caddy and Harvey's older brother, charged up to him and let him have it, then gave him two rules. First, life isn't always "fair"; second, if you want "to change your life you have to change the way you think." The words quieted Willie for the moment, but they stuck with Harvey for a lifetime.[1]

As a golf coach and club pro, Harvey came to understand that some of his players had an inordinate amount of talent, others only a moderate amount. Talent, however, was only the starting point; what was more important was attitude - how you approach practice and how long you practice translate into how well you play the game. That insight is fundamental to coaching - getting the individual to understand that his or her ultimate success or failure will begin with an attitude of how. To put it another way, coaching begins with preparation, preparing to improve one step at a time.

It was always Harvey Penick's philosophy that if a player was prepared for the little things, that player would be prepared to handle the major challenges that he or she would encounter while playing in tight games, where one decision or one movement could determine a championship. More important, Penick, like all good coaches, was a teacher, and he was preparing his players for the larger arena: life after college, after sports - in the "real world."

Preparation is one of the greatest lessons any coach can teach his or her players. Preparation is really another word for investment, and that is essentially what coaching, or teaching, is all about: It is an investment of time and care in the life of another individual that prepares that individual for the challenges that lie ahead. The challenge may be a project that needs completing, a new job that needs tackling, or the selection of a new career path. Coaching is the investment in human capital that opens the door for individual and organizational performance improvement.

Leadership communication leads to a personal connection between leader and follower. This connection can form the foundation of a coaching relationship that enables the leader to challenge the individual to achieve while providing support built upon trust.

Coaching is also a key leadership behavior. Effective leadership, after all, is an investment in the good of others for the good of the whole group. Leaders who succeed are those who incorporate the agendas of others into their own agendas. Leaders who coach are essential to the health of every organization. Good leaders are natural coaches in their own right. Some business leaders serve as cheerleaders for the achievements of their teams; they want the teams to win and succeed. Other leaders work one-on-one, or behind the scenes, to develop their people so that their people are prepared to assume ever-greater leadership responsibilities.

Like communications, good coaching is a two-way street. To be successful, coaching requires the commitment of the individual player or employee. Coaching enables individuals to fulfill their potential, to be what they are capable of becoming for themselves, their team, and their company. Organizations succeed because of the people running them. The more exciting the enterprise - be it in business, government, or social service - the more commitment it requires.

One of the maxims of coaching is that its purpose is to move people from compliance (going along with the flow and not making waves) to commitment (making a difference and creating waves if necessary). Commitment can occur, however, only if the goals of the individual and the goals of the organization are in synch. If they are, then good things can happen; if they are not, then it is up to the coach to help get them into alignment. The coach can persuade the individual that the organization needs and wants her or him, and that therefore the individual should make a commitment. For example, if a computer engineer is not demonstrating the right degree of care and attention to detail in his or her work, it is up to the team leader to point out the engineer's deficiencies and suggest improvements. Furthermore, the team leader may draw a link between individual slackness and weakness in corporate return on investment. The leader then demonstrates that the engineer's deficiencies are hurting not just the engineer, but also the entire company. In this way, coaching plays a role in both individual and corporate development.

Alignment of Personal and Corporate Goals

Coaching can be an effective means of aligning individual aspirations with organizational goals. It is the coach's responsibility to bring out the talent within the individual and to ensure that there is a good match between that talent and the organization's needs. For example, an accountant wants to work in a place where she or he can use her or his analytical skills and make a contribution to corporate objectives. The company needs good accountants to manage its finances in order to achieve its fiscal goals. In this situation, the goals of the employee and the company are aligned. Sometimes such alignment of goals may not be possible. If, for example, an employee prefers working solo rather than as a part of a team, an organization where team culture rules may not be a good fit. The coach can advise the individual that he or she might be happier working somewhere else, in a more autonomous environment. And this can be good news. A number of successful entrepreneurs have left the shelter of large organizations because they craved the independence of running their own business. And some will admit that they based their decision to leave on the advice of well-intentioned coaches.

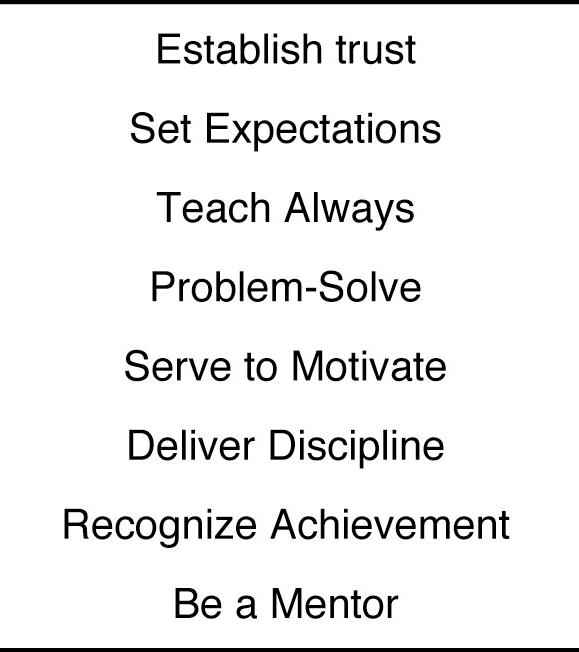

Here are eight ways to begin to develop a strong coaching technique (see Figure 10-1).

Establish Trust

Trust is at the core of every coaching relationship. To build a sense of trust, a leader-coach must communicate that he or she has the individual's best interest at heart, and that whatever he or she says or does is done with the individual's best interest in mind. Once the coach and the recipient understand each other, they can create a relationship of mutual benefit. The coach helps the individual achieve personal goals, and the individual helps the coach realize organizational goals. Harvey Penick, throughout his seven decades of coaching championship golfers, founded his relationships on trust; players understood that Penick wanted them to excel, and so they should listen to his counsel. At the same time, Penick did not mold players to a specific swing pattern; he worked within the physical capabilities of each player. This approach depends fundamentally upon respect for a player's talent and engenders trust.

Few things earn the respect of a team more than a coach's willingness to accept criticism in public. In sports, good coaches never publicly blame the players or their assistants for a defeat. They take the criticism. Behind closed doors, within the confines of "family," a coach will rip into players who need ripping into, just as he or she will praise those who are deserving of praise. Corporate leader-coaches can do the same. They should stand up for their people in front of senior management and do whatever is possible to provide their employees with the support and the resources they need if they are to perform. Advocating on behalf of employees is a sure way to gain employees' respect. But a coach must be skillful about this; he or she cannot alienate the management team. Coaches, too, need to maintain the trust of the bosses.

Set Expectations

The individual needs to know what is expected of her or him, and it is up to the coach to be specific about what is needed. As an extension of the goals alignment, the leader-coach needs to make certain that the department is aligned with the organizational goals. Furthermore, the coach needs to ensure that the individuals on the team know what they are supposed to do. Many managers ask their direct reports to set their own performance objectives. This practice is a good one, but the manager owes it to both the team and the individuals to contribute to those objectives. A simple sign-off is not good enough; the manager owes the employee a conversation about it.

As part of the conversation on performance, the leader-coach must get the individual's buy-in. And it is here that the manager must be very clear and specific. Make certain that goals and objectives are in writing, and gain agreement on what the individual will do by when. Timeliness and deadlines are essential. If this is not made clear, the employee may legitimately state that he or she will do it when he or she gets around to it. The deadlines add a sense of urgency and lead naturally to the manager's following up and following through. In the wake of the Super Bowl, Tom Brady, as quarterback of his team, set expectations for himself that he wanted to repeat, and as team leader he thereby established expectations for everyone. Brady backed those expectations with a commitment to off-season training.

Teach Always

Teaching is fundamental to coaching; providing information and ensuring that learning occurs is what coaches do. Vince Lombardi, who began his career in coaching as a high school teacher of math and sciences, was first and foremost a teacher. With a piece of chalk and a blackboard, he could talk for hours to players or to fellow coaches at clinics about the Xs and Os of football. Dressed in a sweatshirt and a baseball cap and with a whistle around his neck, Lombardi was the archetypal image of a football coach of his era. Coaching instruction can take many forms. It may be explicit: Pointers on how to operate a piece of machinery, or tips on how to structure a report. Or the instruction may be implicit, such as a parable or a story that the coach relates. What is important is that the coach relates the instruction in ways that the individual can accept and understand.

For this reason, coaches must be active listeners, attentive to communication clues. Blank stares or bored looks indicate that the lesson has no meaning. Conversely, head nods and questions mean that the lesson may be getting through. The coach must work to find methods to engage the employee's interest and hold it so that learning does occur.

It is no coincidence that many coaches are good storytellers. Stories offer the opportunity to impart important life lessons in a manner that is accessible and even enjoyable rather than condescending and preachy. For this reason, coaches keep a personal inventory of stories intended to evoke the appropriate emotion for the situation - admiration, inspiration, tears, or laughter. Importantly, all of these stories contain a pithy message wrapped neatly inside. (See Chapter 12)

Problem-Solve

Coaches must possess a sixth sense about individual performance as well as team performance. In basketball, when one team begins a scoring run, the opposing coach will often call a time-out. He will pull the team together (physically and mentally) to focus its energies on the task at hand. He will point out both what the team is doing wrong and what it is capable of doing. Great coaches can turn around team performance in a matter of minutes. In business, good coaches have similar abilities. They can rally a team around a goal and provide direction. When the team encounters an obstacle, the coach finds ways to overcome or avoid the problem. Specifically, good coaches go around to each team member and ask what type of help that team member needs: time, resources, or staff. Coaches then affirm the individual's value to the project and provide ongoing encouragement. Jack Welch, a Ph.D. chemist turned manager, learned early that a successful career in management depended upon an ability to solve problems. He continued to preach that throughout his career.

Similarly, if there are personality conflicts, it is up to the coach to intervene. Often the coach cannot impose a solution, other than forced separation, but he or she can try to get to the root of the problem and discover ways for the individuals who are at loggerheads to work together. Ideally, a solution will come from the two parties themselves, but it will be the coach who brings them together and gets them talking.

And keep in mind that coaches do not wait for problems to occur. As leaders who exemplify the "management by walking around" philosophy, they have their antennae tuned to the rhythm of the team. They are responsible not simply for maintaining morale, but for invigorating it. When coaches sense that something is amiss, they seek out the cause immediately. Likewise, when a crisis occurs, they do not hesitate to intervene. Good coaches drop everything and move to solve the problem immediately. Quick action has three benefits: It can provide immediate relief and ameliorate the situation, it can prevent a small problem from growing larger, and it demonstrates to the organization that the coach has people's best interests at heart.

Serve to Motivate

Good coaches are known as masters of motivation; they prod their teams to win. Motivation, of course, cannot be imposed upon an individual; it stems from the person's inner drive to achieve. What coaches can do is establish an environment in which individuals can thrive. They can, as mentioned earlier, provide alignment between the goals of the individual and the goals of the organization. At the same time, good motivators need to know when to push and when to hold back. Some individuals need someone prodding them all the time; others prefer a laid-back, hands-off approach. It is the coach who designs a system, or an approach, that is tailored to bring out the best in the individual for the good of everyone. Part of that system includes a healthy dose of recognition for a job well done. Joe Torre of the Yankees is a coach who knows how to do all three - prod the player who may be slacking, encourage the player who is struggling, and frequently recognize everyone who is doing a good job.

Deliver Discipline

Not everyone responds to advice. Metaphorically speaking, sometimes the stick can be more effective than the carrot. Discipline connotes compliance with the rules, be they rules of quality control or rules of conduct. Delivering discipline, therefore, is another form of maintaining standards and ensuring that behavior has consequences. We see this often in the world of sports. A coach will bench a star player because the player is not practicing hard enough, or because the player is not demonstrating commitment to the team. In the workplace, a leader-coach can call aside an employee who is not pulling his or her weight, e.g., not sharing information with other employees, showing up late for meetings, or regularly leaving work early. The coach can warn the employee that if the deficient behavior does not improve, the employee will suffer the consequences: restriction of perks, forfeit of bonus pay, or the loss of a promotion.

Discipline will be effective, however, only when it is backed by trust. Every coach must focus on behavior (what the person does) rather than personality (what the person is) and must communicate that any punishment is due to deficient behavior. Vince Lombardi was famous for having a star player or two whom he could publicly excoriate. Sometimes this was deserved; other times it was an act to get the team's attention. Lombardi did not want to play favorites, and when he purposely went after a star player, everyone else would fall into line.

Discipline need not always connote punishment. Discipline can take the form of adhering to a value system, even in the face of adversity. Coaches teach discipline not so much by their words as by their example. When employees see a coach making a tough decision, particularly one that involves personal inconvenience, they learn to respect that coach. Effective discipline ultimately leads to self-discipline, with employees taking responsibility for themselves and their actions. When this occurs, the coach has done the job.

Recognize Achievement

The flip side of discipline is recognition. Individuals who do a good job need to be recognized. Recognition accomplishes several things: It lets the person know that she or he is doing a good job, it helps raise the person's confidence and encourages him or her to continue achieving, and it lets others know that the individual is doing a good job and is appreciated. Rudy Giuliani recognizes the contributions of his people by mentioning their names in his writings and his public statements. Shelly Lazarus at Ogilvy & Mather fosters a culture in which individual contributions matter; she calls her agency a "meritocracy."[3] Mother Teresa believed that recognition for service has its own rewards, the sense of serving God by serving the people who are most in need.

It is important to separate the concepts of recognition and reward. Recognition is the acknowledgement that someone has done a good job; reward is the benefit associated with the recognition. In other words, employees are recognized for a good job and rewarded with a gift or bonus. Many companies practice pay for performance, awarding bonuses for the achievement of goals. While people may debate the benefits of this system, in such a system it falls to the manager, who sometimes also functions as coach, to evaluate an individual's eligibility for bonus. This practice clouds the development role of coaching because it equates development with compensation. The two are independent of each other. Compensation is linked to job performance; development is linked to individual growth and improvement. Good coaches, therefore, must learn to separate their role as arbiters of compensation from their role as developer of talent - not an easy task.

Be a Mentor

What is a mentor? A friend, colleague, and adviser, all rolled into one. A mentor is a friend in the sense that he or she has the person's best interests at heart. A mentor is a colleague who is not afraid or unwilling to dispense advice that the individual may not want to hear, but needs to hear. A mentor is an adviser who looks toward the future, who dispenses wisdom that is directed toward the current but mostly the future needs of the individual. Yiddish has a wonderful word for mentor, mensch, a person who can be counted on to be a good friend and to be of assistance in times of need. That's not a bad summary of mentorship.

People have a desire for guidance. Just as children are taught life values by their parents, employees are taught workplace values by their "superiors" (managers, old-timers, retirees). Counsel is a form of advice. The good coach aligns advice within a value system. For example, a coach may advise an employee to show up on time as a means of demonstrating a commitment to fellow employees. Timeliness is a lifestyle value that extends far beyond the work environment. Likewise, the coach may advise an employee to listen more attentively when a colleague speaks. Again, a good life lesson.

Very importantly, coaches give counsel through example. The old adage "Do as I say, not as I do" cannot apply to coaches. A coach who advises an employee to listen, but always talks over other people, undermines her or his own advice. Leader-coaches do not have the luxury of slacking off when it comes to advice giving.

Mentoring, by the way, can be a temporary or a long-term commitment. General George C. Marshall was a mentor to many up-and-coming officers. He kept their names in his famous "black book," and when the time came for a new generation of leaders to rise to the challenge, as happened at the outset of World War II, Marshall knew whom to promote. Many people come back to their mentors for ongoing advice at various stages of their lives. Others seek a mentor for a given assignment. Mentorships, by the way, are gaining in popularity within the corporate arena for two reasons: First, young employees need guidance, particularly when it comes to navigating the sometimes-treacherous waterways of corporate channels, and second, mentors need experience in giving advice as a form of teaching. By being mentors, they learn more about themselves and their potential for greater leadership positions. Mentorship does have mutual rewards.

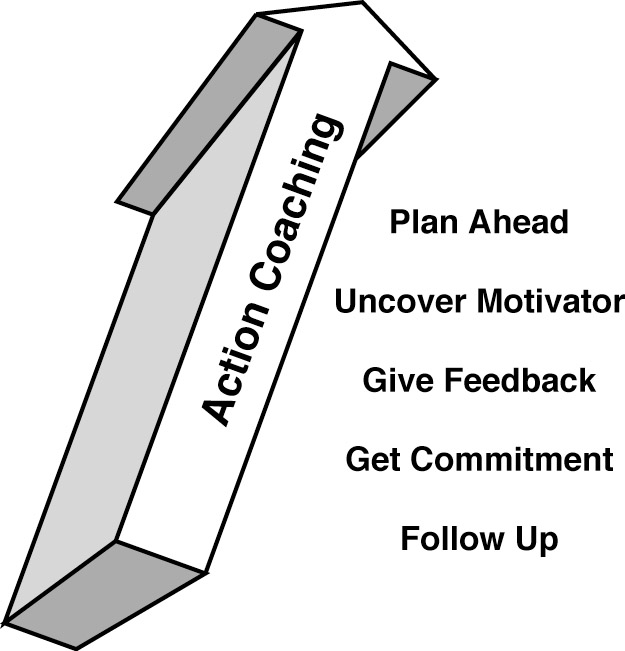

Action Coaching Model

Coaching should be an integral part of a leader's job. It is not something that should be undertaken lightly. It requires preparation, critical thinking, and follow-through (see Figure 10-2). Leaders also need something more - a healthy dose of emotional intelligence, e.g., the ability to understand someone else and your relationship to that individual.

Plan ahead. Identify the individual you wish to coach. Schedule a time to meet. Allow at least 30 minutes, and preferably 1 hour. Look at the work the individual has been doing. Ask coworkers about the individual. Look for problem areas. Keep in mind that you are looking for areas of weakness, not to punish the individual for them, but rather to strengthen her or him. That's what coaching is all about.

Uncover the motivational tick factor. Think about what motivates this individual. Is it an opportunity to be promoted? Is it more money? Is it the quest for a better life for her- or himself and her or his family? Does this individual value time off in lieu of overtime pay? Discovering the motivational tick factor opens the door for understanding.

Give feedback. Open with small talk. If you know the individual well, you will know his or her likes and dislikes. Some of us like to talk about our families; others prefer not to. Some of us like sports, cooking, camping, biking, you name it; others could care less about any or all of these.

As the coach, you need to identify an individual strength - something that the person is doing very well. Say something positive about the person's performance. Then move to the areas of weakness, things that the individual could be doing better. Call them "opportunities for improvement." First find out what the individual thinks about the situation.

Ask if there is anything holding the individual back or preventing her or him from doing the job. These obstacles could be a lack of resources, not enough time, or another individual - even the leader. Typically such problems not only are harmful to the individual but may be harming the entire team. Emphasize your willingness to help. Ask the individual if he or she has any suggestions for improvement.

Get commitment. Identify solutions to the problems. Ask the individual to commit to improvement. Gain agreement. Establish a time frame for resolving the problem. Again, gain agreement. Close the session on a positive note. Thank the individual for his or her contributions. Ask for feedback on your coaching style. Was it helpful? How could you have made it better? (If you are open and forthcoming, you will get honest feedback. It may take a few sessions for the individual to open up, but in time she or he will - if you have established the proper boundaries of trust.)

Follow up. Check on the individual periodically. Feedback during the workweek is perfectly acceptable. Do not ride the person. Just be available. When the agreed-upon deadline is reached, check on the status of the situation. If the problem has been resolved, recognize the individual for meeting the commitment that he or she made. If the problem has not been resolved, ask why. You may need to schedule another coaching session, or at least keep a close watch on the situation.

As the leader, you want to be able to resolve any issues, but you also want to enable individuals to solve as many of the difficulties as possible for themselves. Too much intervention indicates that you are doing too much, to the detriment of others on the team. This also thwarts the growth of the individual. Too little intervention leaves the individual to sink or swim. Sometimes that is appropriate; other times it is not. When you follow up, make certain that you ask for feedback on your coaching style. Again ask how you can improve.

Continuous Coaching

As mentioned, coaching is integral to leadership. While coaching sessions need to be planned in advance, informal coaching can occur at any time or at any place. Often this is nothing more than giving feedback, positive or negative. Keep to the rule of opening with a positive and ending with a commitment to improvement.

One more point: We have emphasized coaching as a leadership behavior, assuming a leader-to-subordinate direction. Peer coaching is equally valuable. And so is "upward coaching" - e.g., coaching your boss. Follow the same process outlined in the action coaching model. The outcome will be increased trust and improved performance. And whenever you can bring that out in another person, it's a leadership action.

Coach as Leader

Coaching and leadership go hand in hand. From creating trust through discipline, reward, and mentorship, coaching behaviors exemplify leadership behaviors; in fact, they are leadership behaviors. All coaching behaviors are centered around strong organizational goals and work together to reinforce the coach-individual relationship. In doing so, they create a situation in which the individual as well as the team can thrive.

Fundamentally, coaches, like leaders, are teachers. They teach by their words as well as lead by their actions. Harvey Penick and Vince Lombardi draw life lessons from the task at hand. Through coaching, the individual acquires job skills, but more important, she or he also gains knowledge about life itself. It is the life lesson that matters most in a person's development. It is an investment in the person's future to which leader-coaches must continually strive to contribute.

Vince Lombardi - The Teacher as Coach

There are times in a leader's life when that leader is defined by what he or she does or does not do in a particular moment. Looking back at successful leaders, we sometimes assume that they were always good, always made the right decision, or always said the right thing. One such moment came for Vince Lombardi when he became the head coach of the Green Bay Packers. Today the success of the Lombardi Packers is legend, and so we have to peer into the history books to recall what a woeful team they were when Lombardi became their coach in 1959 - the year before, they had won only a single game.[4]

The Long Climb

For Lombardi, coming to the Packers was the culmination of a long climb from Fordham University, where he had been a lineman, one of the seven blocks of granite, on a winning football team. After considering the priesthood, Lombardi eventually started his coaching career modestly - as the head coach of St. Cecilia's basketball team. He felt that he "wanted to be a teacher more than a coach." And teach he did: "physics, chemistry and Latin," all rigorous subjects. He was also the assistant football coach. (His basketball team posted a winning record in Lombardi's first year.)[5]

After eight years at St. Cecilia's, where he eventually became head football coach, and a successful one at that, he moved to the collegiate ranks at Fordham and later to Army as an assistant to the legendary Red Blaik. He then became an assistant coach for the New York Giants and finally, 5 long years later, moved to the Packers. While the job might not have been a prize to other coaches, it was heaven to Lombardi, and so it was with great excitement, mixed with apprehension, that he introduced himself to the team at summer camp.

Quintessential Lombardi

According to his biographer, David Maraniss, Lombardi had rehearsed over and over again what he would say to his new team. He began with the practical - taking care of the playbook and always being on time. He would keep practices short, no more than 90 minutes twice a day, as Red Blaik had done. There would be a difference, however: The practices would be tightly planned, and the players would know what they were "supposed to be doing every minute." As a result, Lombardi wanted his players on the field and ready to go at exactly the appointed hour - "prepared" and ready to learn.[6]

Then he launched into what has become known as the quintessential Lombardi lesson, which has sometimes been lost in the legend of the fiery coach's rhetoric. He spoke of how he - the coach - would "be relentless" in pushing them to try, try, and eventually succeed. His expectation for them was that they would keep in shape. He by example would do the rest - the pushing, the prodding, the yelling, and, of course, the teaching. When Lombardi finished, the room was silent until Lombardi dismissed them. Moments later, the coach pulled aside one of the players and asked how he had done. Max McGhee, the All-Pro veteran, responded, "Well, I'll tell ya, you got their attention, Coach."[7]

What Lombardi had done was put the onus of winning upon himself. He took the pressure off them as players and carried it on his own shoulders. Of course, the players would have to work hard and abide by the rules, but Lombardi would take care of the rest. He would challenge each player privately to elevate his own expectations of himself, and the entire team collectively would benefit. Sly fox that Lombardi was, he pushed and pushed, but with the tacit approval of the players, who believed in themselves enough to feel that they could succeed.

Teaching the Sweep

Lombardi was first and foremost a great teacher. His greatest football lesson was the powerful motion to the strong side of the field, right into the teeth of the opposition. It became known as the Green Bay Sweep, and from this formation Lombardi devised a number of running and passing variations that would keep the other team off balance and his team in control. It was important, Lombardi said, for a team to have one play that the players felt they could run and run well; it would become, in our parlance, the "go to" play - one that would do more than gain yardage, it would instill confidence and rally the team..[8]

The Legend Speaks

In their first year under Lombardi, the Packers finished third and Lombardi was named coach of the year.[9] In his second year, 1960, the team captured the league championship, and in his third year, 1961, the Packers took the NFL title - the first of five titles. The team capped its final two seasons under Lombardi with wins in Super Bowls I and II, games that in those days were little more than afterthoughts because it was believed that the AFL, the upstart rival conference, was not up to NFL standards. (Super Bowl III would change that perception when Joe Namath led the New York Jets to a win over the Baltimore Colts.)

Winning brought fame to Lombardi and, not surprisingly, offers to join the lecture circuit. Lombardi crafted a speech built on "seven themes."[10] All of these themes are relevant to who Lombardi is as a person; three of them tell us about him as a leader.

Discipline. Speaking during the tumult of the sixties, Lombardi did not really understand the divisiveness that those times provoked. While he could be faulted for not listening to what young people at the time were rebelling against - war, conventionalism, and materialism - his words on the need for discipline are timeless. People, according to Lombardi, want to be led and will respond to and appreciate a leader who instills discipline.[11]

Leadership. Educated formally by the Jesuits at Fordham and informally by Red Blaik at West Point, Lombardi had seen leadership close-up. In fact, while he was at West Point, he got to know General Douglas MacArthur when he gave MacArthur private screenings of Army football games.[12] Lombardi said, "Leaders are made, not born. They are made by hard effort, which is the price all of us must pay to achieve any goal that is worthwhile." Leaders need to balance "mental toughness and love." Toughness emerges from discipline; love emanates from loyalty and teamwork.[13]

Character and will. Leadership is built upon character and will. The Jesuits taught Lombardi that character and will are linked forever in a virtuous cycle - character "superimposed on" will, and will "as character in action."[14] Lombardi concluded:

The character . . . is man's greatest need and man's greatest safeguard, because character is higher than intellect. . . . [T]he new leadership is in sacrifice, it is in self-denial, it is in love and loyalty, it is in fearlessness, it is in humility, and it is in the perfectly disciplined will.[15]

Relevant Legend

The question arises as to whether Lombardi has any relevance in today's world. The answer is, of course![16] His strength of character and his determined spirit are timeless, but for those of us looking at leadership communications, in his ability to teach and to coach (and with Lombardi they blend together), his example stands the test of time.

Harvey Penick - Lessons from a Pro

When you think of leadership communications, chances are you don't think of golf. After all, golf, even in its competitive form, is chiefly a solitary game - one course, one player. Communications are chiefly internal; players and caddies are allowed to converse, and players of course speak to one another, but the game itself revolves around finding the shortest and best way to put the ball into the hole using nothing more than variously fashioned clubs, all derived from an ancient game that Scottish shepherds once played.

Well, there is an exception - the communication that occurs between a player and his or her coach. Plenty is said during coaching sessions, and in fact you can make the case that the lessons imparted on the golf range or in the clubhouse must be the most enduring, since player and coach are not allowed to converse during a match. The player must rely on lessons reiterated, reinforced, and remembered. One master of such teaching is Harvey Penick, a golf teacher for more than 70 years and a best-selling author as an octogenarian and even nonagenarian. His lessons were simple, straightforward, and down to earth. In his own unique way, Penick was a leader who was able to communicate with a directness that was as effective as it was heartfelt.

Getting the Word Out

Harvey Penick was a coach at the University of Texas as well as being club pro at the Austin Country Club in Texas. Along the way, he nurtured the careers of many a great player: Tom Kite, Ben Crenshaw, Mickey Wright, and many others. He himself had played collegiate golf and had flirted with the professional game. But watching (and hearing) Sam Snead shape his shots so purely and accurately made Penick realize that if he were to remain in golf, his place was in shaping the talents of others.[17 ]Along the way, Penick kept notes on what he told his players, and over the years the range and volume of his notes grew. It was his son, Tinsley, also a club pro, who urged him to publish.[18 ]

And what happened next tells you all you need to know about Harvey Penick. Bud Shrake, a respected sportswriter and novelist with a pedigree that included Sports Illustrated, teamed with Penick to do a book. The story goes that Shrake informed Penick that "his share" from the book deal would be $85,000. Harvey was aghast: "Bud, I don't think I can raise that kind of money."[19] What this story says about Penick is this: He was humble (a publisher wants to pay me!), and he was a teacher (he wanted to share the lessons he had learned himself and imparted to his pupils over a long lifetime of teaching a game he loved). The first tome, Harvey Penick's Little Red Book, became one of the best-selling sports books of all time and led to a series of subsequent books, television appearances, a video, and eventual worldwide recognition.

Lessons from the Game

Simplicity is something Penick strove for always. Golf is a game of feel: Feel the grip, feel the club head, feel the swing. Most students respond to the simplicity, but Penick recalls the example of the woman who became flustered because he would not add more technical advice. But that was not his style.[20] "Playing golf you learn a form of meditation . . . you learn to focus on the game and clean your mind of worrisome thoughts."[21]

Penick was earnest about his teaching and prayed before beginning one of his teaching clinics; his reason was that "few professions have as much influence on people as the golf pro," and so he wanted the help of the Almighty in this endeavor.[22] At the same time, Penick was perpetually humble about his role in the game, referring to himself as a "grown caddie still studying golf."[23] About his own teaching style, Penick uses the tools of all successful teachers - "images, parables and metaphors."[24] In this way, he could make his pupils see both physically and metaphysically how they could improve their game.

Tribute to Teacher

Penick's students who have gone on to excel in the professional game are themselves legends. Tom Kite and Ben Crenshaw were two of his favorites. Kite won the 1992 U.S. Open and gave his trophy to his tutor to hold.[25] And most movingly, Ben Crenshaw won the 1996 Masters shortly after Penick died. "I could definitely feel him with me. I had a fifteenth club in the bag. The fifteenth club was Harvey."[26]

Shortly before the 1995 Ryder Cup matches between the best American and best European golfers, Penick's son, Tinsley, summed up his father's life in a kind of elegy delivered to the players on the eve of the match. Some of the players knew Penick personally; all of them knew him in some way, if only through the lessons imparted in his books. In his talk, Tinsley spoke of his father's commitment to differences: Each player has his own unique style, and he would not try to change it. And he mentioned Harvey's sense of professionalism, never speaking ill of fellow pros.[27]

Keep on Learning

Tinsley also revealed what might be the secret of Harvey's coaching - he never stopped learning. As a coach at the University of Texas, Harvey made it a point to find out "the methods and teaching techniques" of the person who had taught the player. "My dad gained a lot of knowledge from these experiences."[28 ] And somehow it is fitting that a man who seemingly devoted himself to a game was in reality devoting himself to helping generations of men and women, young and old, find a better way to play the ultimate game - life itself.

[1]Harvey Penick with Bud Shrake, The Game for a Lifetime: More Lessons and Teachings, pp. 159-160.

[2]Harley-Davidson shifted the discussion from values to behaviors. While people can debate values, what often matters more is behaviors, how people interact with others. Behaviors are observable and can be coached. For more insights into the issue of corporate values, refer to Rich Teerlink and Lee Ozley, More than a Motorcycle: The Leadership Journey at Harley-Davidson, pp. 153-157.

[3]Thomas J. Neff and James M. Citrin, Lessons from the Top: The Search for America's Best Business Leaders , pp. 225-226.

[4]David Maraniss, When Pride Still Mattered: A Life of Vince Lombardi, p. 191.

[5]Ibid., pp. 67-87 (quote on "teacher" vs. "coach," p. 69).

[6]Ibid., pp. 216-217.

[7]Ibid., p. 217. Much has been written about Lombardi's motivational style. The last paragraph on page 157 of this guide refers to Lombardi motivating players by raising their own personal expectations. A former player discussed the idea during an ESPN documentary on great coaches.

[8]Ibid., p. 222.

[9]Ibid., pp. 228-230.

[10]Ibid., p. 400.

[11]Ibid., pp. 404-405.

[12]Ibid., p. 145.

[13]Ibid., pp. 405-406.

[14]Ibid., p. 406.

[15]Ibid.

[16]Ibid. Maraniss raises this question about Lombardi's contemporary relevance in the Preface pp. 13-14.

[17 ]Harvey Penick with Bud Shrake, Harvey Penick's Little Red Book: Lessons and Teachings from a Lifetime in Golf, p. 109.

[18 ]Ibid., p. 26.

[19]Clifton Fadiman and Andre Bernard, eds., Bartlett's Book of Anecdotes, rev. ed. , p. 430, quoted in Robert T. Sommers, Golf Anecdotes .

[20]Harvey Penick with Bud Shrake, And If You Play Golf, You're My Friend , pp. 65-67.

[21]Penick with Shrake, Harvey Penick's Little Red Book, p. 74.

[22]Penick with Shrake, And If You Play Golf, You're My Friend, p. 168.

[23]Penick with Shrake, Harvey Penick's Little Red Book, p. 73.

[24]Ibid., p. 25.

[25]Penick with Shrake, And If You Play Golf, You're My Friend, pp. 62-63.

[26]Penick with Shrake, Game for a Lifetime, p. 20.

[27]Tinsley Penick, epilogue to The Game for a Lifetime, by Harvey Penick with Bud Shrake, pp. 201-208.

[28 ]Ibid., p. 207.