Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 5: Defining the Sales Process

Overview

There are lots of people out there - most likely a majority of people - who believe that selling is really an art.

This belief is sustained, in part, by the existence of customer-focused salespeople with innate skills who make selling look so easy. But there are two problems with this assumption. The first is that, as we've already seen, there aren't enough customer-focused salespeople out there to go around - perhaps 10 percent of sales professionals.

The other problem is that it presents a self-fulfilling excuse for not getting better. If selling is an art, and I'm not an artist, then I'm off the hook, right? All I can do is plod along in my traditional selling mode and hope for the best.

We don't agree. What if we could codify the "artful" behaviors of the customer-focused sellers? What if we could build those behaviors into our sales processes and messaging? The truth is that all salespeople, and in particular traditional salespeople, can become more customer-focused, and can produce at higher, more predictable levels. In fact, we have found over the years that a traditional seller following a good process is likely to outperform a naturally talented seller who is winging it.

Sometimes we cite the example of two different kinds of musicians - those in a jazz trio and those in a symphony orchestra. The jazz musicians improvise, in real time. They rarely play the same piece the same way twice. But if you dig a little deeper, you find that there is a great deal of structure and discipline behind most of their improvisation. Meanwhile, the musicians in the orchestra try their hardest to play a Mozart piece (for example) perfectly. For the most part, the members of the orchestra couldn't write music like Mozart's. (No slight intended; how many of us can?) But because Mozart's music has been codified, they can replicate it, and brilliantly.

Naturally talented sellers are very similar to jazz musicians. We can launch a new company with a few naturally talented salespeople (the jazz guys), but to build it big enough to go public and capture its share of market, we will need to teach traditional salespeople (the orchestra) to execute a customer-focused sales process. We have to teach the orchestra to play a little jazz. At the risk of overworking the metaphor, we have to look for the structure that underlies the jazz.

In the enterprise selling world, there are many complicating factors - multiple decision makers, platform sales, commodity sales, relationship sales, application sales, new-name sales, add-on sales, sales through channels, and so on. When we work with our client organizations, one of our first tasks is to help them document, define, and understand all their sales processes. In other words, we help them codify their selling behaviors for the different selling situations they encounter.

Is this necessary? We think so. Many companies define the what, in other words, the things that should be done at each step in their sales process. Most are not so good at codifying messaging that guides the behavior of their sellers and provides the how for these same steps. Unless you establish a set of standards or rules - the how - at each step of the selling process, you have to depend on unreliable data (i.e., the opinions of those around you) or data that come far too late (i.e., your closed orders). If management can proactively assess the quality of what is in the pipeline and help salespeople disqualify low-probability opportunities earlier, pipelines won't be filled with hopes and dreams. Without a process, conversely, management tends to be a series of autopsies performed on dead proposals or lost orders. With process, corrective surgery might have been possible, and the outcome could have been a win.

Have you thought about your sales process? CRM works best for companies with well-defined processes already in place. Automate chaos and it's still chaos.

Larry Tuck, editor of CRM magazine, 2010

Defining the Sales Process

Many companies have established milestones and believe they have process. For traditional sellers, however, this is analogous to giving a destination without a map or directions and occasionally asking if they are going the right way. To chart a different course, it will be necessary to establish some definitions that we can build on:

Process: A defined set of repeatable, interrelated activities with outcomes that feed another activity in the process. Each outcome can be measured, so that adjustments can be made to the activities, the outcomes, or the process itself.

Sales process: A defined set of repeatable, interrelated activities from market awareness through servicing customers that allows communication of progress to date to others within the company. Each activity has an owner and a standard, measurable outcome that provides inputs to another activity. Each result can be assessed, so that improvements can be made to (1) the skills of people performing the activities and / or (2) the sales process.

Sales pipeline milestones: Measurable events that take place during a sales cycle that enable sales management to assess the status of opportunities for the purpose of forecasting. Ideally, most of these milestones are (1) objective and (2) auditable.

Sales funnel milestones: Measurable events that take place on specific opportunities that enable sales management to assess the quality of selling skills and the quantity of activity needed at the salesperson level. Again, these milestones are (1) objective and (2) auditable.

Because of the predominant perception that selling is more art than science, few companies have sales processes that traditional sellers can execute. We believe that this deficiency is the single most significant factor contributing to the disappointing results achieved with sales force automation (SFA) and customer relationship management (CRM) systems. As suggested in the above definitions, the chances of building and sustaining an executable and therefore successful sales process are slim in the absence of the following prerequisites:

Pipeline milestones

Repeatable process

Sales-Primed Communications

Customer Focused Sales skills

Consistent input

SFA and CRM systems are among the most common sales-process management techniques today. The allure of these SFA and CRM systems is that they supposedly give companies better control over their sales efforts, culminating in more accurate forecasting. But most companies attempting to implement SFA or CRM have had only one of these six components in place - the pipeline milestones - and even this tends to be updated based mainly on the opinions of salespeople.

We'd like to drill down further into three of the remaining five areas with two goals in mind: (1) defining the component and (2) offering suggestions as to how to fill any voids that may exist. Then, later in this chapter, we'll return to the pipeline milestones.

Repeatable Process

We've already introduced this idea. What is the "code" that allows the traditional salesperson to become more customer-focused? What constitutes success, and how can more people achieve it?

We should point out at this juncture that most companies have more than one sales process. For example, the selling activities will vary when selling major accounts, national accounts, mid-size accounts, add-on business, professional services, contract renewals, and so forth. Most people quickly realize that one size does not fit all; in fact, it can be a recipe for disaster to impose a single sales process on all sales. (Salespeople are fully within their rights to complain about being asked to kill a mosquito with a cannon.) Later in this chapter, we will address how to handle these different types of sales.

Consistent Input

The majority of the input to SFA/CRM systems consists of salespeople's opinions of the outcome of sales calls they make. By definition, this input is subjective and variable. Compounding the problem is the fact that the positioning of offerings falls almost exclusively on the shoulders of individual salespeople.

Consider how odd this situation is in the larger context of a business enterprise. How many other functional groups get to make this kind of report on their work, without fear of contradiction? How many other numbers that are critically important to the corporation have so much subjectivity built into them?

Auditable Input

As noted above, many companies have defined milestones - that is, clearly identified steps in a sell cycle that are used to determine where the company stands vis-à-vis a given opportunity. But asking traditional salespeople to tell what milestones they have achieved invites them to provide the answer they think their manager wants to hear, and in some cases do so in order to secure their position for another quarter. Unless or until milestones have components specific to job title and business goal that can be audited by someone other than the salesperson, input will continue to be variable. More on this topic later in the chapter.

The Trouble with the Data

We don't mean to imply that companies implementing SFA/CRM systems have failed to realize any benefit, especially in the realm of improvements in forecasting accuracy. Indeed, many have experienced some success in that area. But in many cases, part of the difficulty with these implementations has to do with poorly managed expectations about how much forecasting accuracy will increase, and when.

A few years ago, while working with a CRM vendor, we asked the vice president (VP) of Sales if the company "ate its own dog food" (i.e., used its own software to forecast). This question elicited an enthusiastic yes! from this executive. He then went on to say that he usually came within 5 percent of his quarterly forecast - a level of accuracy most sales executives can only dream about. We asked for details, and within seconds, he had his laptop fired up so that he could share his forecasting secrets with us.

He showed us that the company had defined seven milestones in its sales pipeline. Beginning with the first month that a salesperson started reporting on his or her pipeline, the software heuristically captured close rates at each of the milestones. When it came time to forecast, the software took each salesperson's gross pipeline and applied that salesperson's unique factors to the dollar volume represented by each of the seven milestones. In this way, he achieved his enviable forecasting accuracy.

We then asked: "Are your salespeople telling their prospects that if they use your software package, they will achieve a similar degree of forecasting accuracy?" He acknowledged that, as we hoped and expected, they were.

Next, we began to dissect how his miraculous results were being achieved, and the degree to which other companies would find them replicable. The hard fact was that it would take months or years for other companies to gain the historical close rates by salesperson that were the key component in our client's ability to predict revenue. Ironically, the only reason he could be so accurate with his forecast is that the software tracked historically how inaccurate (i.e., overoptimistic) his salespeople tended to be, in that they overstated their pipelines at each of their seven pipeline milestones. Any new users of this CRM system - in other words, all the new purchasers of the software - could only assign estimates of close rates at various milestones. Most likely, these would be across the board for all salespeople, and would become homed in at the individual salesperson level only over time.

Even with the software in place and defined milestones, moreover, forecasting accuracy could continue to be adversely affected by a range of internal and external factors:

When salespeople leave, their historical data are no longer relevant.

When new hires join, there are no historical data.

Salespeople who are below quota are liable to overstate their pipeline.

New offerings don't have the benefit of historical data.

New vertical industries present new challenges.

A changing economic climate can undercut the relevance of historical data.

The changing fortunes of clients within the product segment can similarly undercut historical data.

Offerings by competitors may raise the bar.

Fire Drills and Hail Marys

Under the best of circumstances, the analysis of the pipeline is based on input from the sales organization. Notable by its absence is any input from the buyer (which, as you'll see in later chapters, could give sales management a way to audit where the buyer stands in the buying cycle, and therefore provide a sanity check). With or without a CRM system, leaving the buyer out of the picture often means that the timing of asking for the business is much more a function of when the company wants (or needs) the order than of when the prospect or customer is ready to buy. In other words, it is rarely customer-focused.

Many companies spend the last few days of nearly every quarter attempting to squeeze out business in order to make their numbers. Many senior executives leave their calendars open during the last week of the quarter, allowing them to embark on "closing junkets." The tool commonly used to get buyers to commit earlier than planned is substantial discounting. Some buyers are so offended by this approach ("I was naïve to assume that the initial price they quoted was real!" or worse, "They must think I'm an idiot!") that they ultimately decide not to do business with a company that employs these kinds of traditional closing techniques.

One difficulty with selling in this fashion is that it tends to turn into standard operating procedure. Emptying the pipeline at the end of March is likely to transform April and May into the months for rebuilding the pipeline, but not closing much business. This culminates in another high-pressure close toward the end of June. Another difficulty is that savvy buyers learn to delay buying decisions, in the knowledge that they will get the absolute best price at quarter's end.

Are you skeptical that such "fire drills" are commonplace among established and reputable companies? Consider the following quote by CA Technologies chief financial officer from an article in Forbes:

Negotiations [at CA Technologies] came down to the last day of the quarter, with Hail Mary discounts of up to 55 percent fairly common in the business. In the quarter ended September 30, 2010, CA did $1 billion of its $1.6 billion in revenues in the last week. We ended up trading phone calls at 11 at night.

Prior to our consulting with them, one company entered the last quarter of a particular year with a chance to achieve $300 million in revenue - a threshold they had never before attained. Senior management then decided that this target was within their reach, and instructed managers and salespeople to close everything they could (i.e., go as low as necessary) so that the goal could be achieved. The good news is they succeeded, booking a few million dollars beyond the magic number. At the subsequent January kick-off meeting, jackets were distributed to everyone with that record year's revenue figure embroidered on the sleeves. The meeting proceeded with a general sense of satisfaction, accomplishment, and even euphoria. Success was in the air!

Then came the bad news. As a division of a larger company, the company received its quota from on high. The objective assigned by the parent company for the following year was $360 million - a 20 percent increase over the record revenue that had just been delivered. As you might expect, virtually nothing closed in January and February, as a result of emptying the pipeline in December. The company finished the first quarter with bookings below 50 percent year-to-date. Ultimately, it stumbled its way toward matching the revenue delivered the previous year - but not before both the chief executive officer (CEO) and the VP of Marketing were relieved of their duties midway through the second quarter. With 20-20 hindsight, the results were predictable, as the company effectively had a 10-month year to produce the revenue. You can imagine the resulting impact on profitability.

Even without being instructed to do so by their management team, many traditional salespeople are guilty of closing prematurely, often attempting to close the wrong person. Attempting to close non-decision makers (and close them prematurely) can cause several bad things to happen:

The person being closed on may end up feeling inadequate or insignificant.

You may convey the stress you are experiencing to the buyer, even to the point of appearing desperate.

The person may become a messenger to the decision maker about your discounted pricing.

If the decision maker is serious about doing business, the discount you provide to the person who cannot buy may become the starting point for negotiating further concessions.

If the order is not closed during the quarter, you may have set an expectation of pricing that you may be unwilling or unable to meet, based on your situation when the decision can be made early in the next quarter.

You may lose the transaction because of your bad behavior.

A sales process should contain a specified time to close that was agreed to by the buyer. Senior management can attempt to accelerate orders at their own risk.

Shaping Your Perception in the Marketplace

In most cases, companies think of their sales process as a way to control cost of sales, facilitate management of the sales force, and forecast top-line revenue more accurately.

These are all valid objectives, of course. But we take things one step further. We believe that a sales process should create a framework for relating to customers and prospects. Think about it: Many organizations develop reputations and are assigned a personality by their behavior in the marketplace. Companies become known as aggressive (Siebel and Oracle), predatory (Microsoft), arrogant (Accenture), and so on. How does this happen? In part, it happens through corporate policies, public utterances of the CEO, and similar high-level actions. But we believe that the behavior of the company's representatives in the field deserves at least as much credit (or blame).

By extension, we believe that it is possible to shape the marketplace's opinion of you by designing a customer-focused sales process that reflects the way you want your customers and prospects to be treated. In other words, the CEO can create a blueprint for customers' experience that will influence the words that salespeople use when developing buyer needs and setting expectations. We believe with equal or even slightly inferior offerings, companies can make the way their salespeople sell a differentiator. These organizations can win on sales process.

What Are the Component Parts?

A customer-focused sales process needs to cover all the steps, from market awareness through measuring results achieved by customers. It should define and comprise:

When buying cycles begin

The steps involved in making a recommendation

The steps necessary to have the buyers understand their requirements

The steps needed for buyers to understand how your offering addresses their goals and problems

An estimated decision date documented to confirm the buyer's agreement

Built-in feedback loops, to permit a rapid adjustment to timing issues, competitive pressures, client feedback, market issues, and external events (e.g., 9/11, Y2K)

One way of structuring a sales process is to define an appropriate set of pipeline milestones, as mentioned earlier. Consider, for example, the following set of milestones in a typical sales process:

Access to decision maker

Return on investment (ROI) completed

ROI agreed to by prospect

Billable event

Customer resources committed

Budget allocated (whose?)

Meeting with Information Technology (IT)

Business issue(s) shared or admitted

IT technical approval

Corporate visit

Implementation plan

Executive call

Professional services call

Specific titles called on

Non-IT champion

Demonstration

Proposal submitted

Reference site visit

Site survey

References provided

Verbal agreement

Client financials received

On-site survey

Financials requested by prospect

Pilot agreed to

Competitors identified

Projected decision date

Price quotation

Compelling reason to buy

Contracts submitted to legal

Call made by services staff

Billable education

The approval of cutover

First-level manager call

Trial

Project start date defined

Credit approval

How do you identify milestones? In addition to drawing on your own experience and process, as well as the list above, we recommend analyzing transactions from the past year or so to determine if you can isolate common factors and patterns in opportunities that you've won and lost. By so doing, it is often possible to identify and incorporate specific best practice events and use them as milestones. This can allow organizations to begin to institutionalize their best practices within a sales process and improve win rates on opportunities in the pipeline.

One company we worked with sells software, and would not allow opportunities to be qualified past a certain level unless the salesperson had made calls on business people outside of the IT department. This milestone was created because history showed that many sales cycles that began within IT ended suddenly, and unhappily, as soon as a request for funds was made without having built a business case that end-users could present to their line of business executives. On the more positive side, another client discovered that when prospects came for a corporate visit, they had an 88 percent close rate on those opportunities. Guess what recommendation we made that became a step in their sales process?

These milestones allow salespeople and management to better understand where they are in a given sell cycle. Just as important - or maybe more important - they provide insight into whether opportunities are qualified, and therefore worthy of resources. As noted in earlier chapters, many traditional salespeople take comfort in having quantity, rather than quality, in their pipelines. They are competing to keep busy, rather than to win.

Key steps in every sales process must be documented in order to be auditable. In other words, there must be a letter, fax, or e-mail from the salesperson to the buyer that summarizes key conversations. Such documentation serves multiple purposes:

It maximizes the chances that both the salesperson and the buyer understand where they are.

It allows consistent internal messaging by the buyer, within his or her organization.

It allows the first Key Player in a committee sale to communicate his or her vision clearly to peers and superiors.

It minimizes the chance that the salesperson is overoptimistic ("happy ears").

Most important, it allows the manager to audit and grade the opportunity.

Note that not all milestones need to be auditable. Your goal should be to define those critical ones that will allow you (or your sales managers) to grade opportunities. This is the only way to get away from the unbridled optimism (i.e., in salespeople's opinions) described earlier.

Senior management must take ownership of the customer experience and the corresponding sales process, in part by defining deliverables based on the size and complexity of a given transaction. If this is not done by management, salespeople will do it in a more informal manner - often at the annual kick-off meeting - in ways that undercut the sales process. Consider the following imaginary (but entirely plausible) exchange:

Salesperson 1: What was your largest transaction this year without following the process?

Salesperson 2: $60,000.

Salesperson 1: Wow, mine was $30,000.

Salesperson 3: Got you both. Mine was $85,000!

The simple fact is, salespeople tend to resist following a process. As a rule, they don't like documenting their sales efforts. And - still in the spirit of generalization - they like to boast of their successes outside the process, which they tend to see as bureaucratic and intrusive. In the conversation above, a policy decision has been made informally by staff who have no authority to do so.

Consider for a moment how much money it costs an organization to compete on a major transaction and lose. According to Gartner Group, the cost per sales call by a salesperson working for a high tech company is about $450, when all compensation and costs are factored in. On a major opportunity, if you were to add in management calls, support people, demonstrations, plane trips, and so on, the cost to compete on a major opportunity over the course of 6 months could easily be $30,000.

Seen in that context, is it reasonable to require that the salesperson be able to document where he or she is in the opportunity, so that the sales manager can determine if it is qualified and warrants the allocation of additional resources?

Salespeople (especially those who are not year to date against quota) intuitively know how much needs to be in their pipelines to keep their managers off their backs. When their pipelines are thin, salespeople become less selective about what they are working on. Along with the compromise in quality of opportunities comes an increasingly unbridled optimism. Here's another dialogue that may sound familiar:

Salesperson: As you know, boss, things have been slow for me the last 4 months. I've been in a slump. But this is my month! Grab onto my coattails, because we're going to have a huge month!

Manager: Let's run through your forecast.

Salesperson: O.K. Unexpectedly, I received an RFP this week. It looks like it was wired for us. They're going to make a decision by the end of the month. I figure it to be about an 80 percent chance. I just spoke with the ABC Company. The proposal has been sitting there for 90 days, but my friend in the account says management is getting serious again. And there's another one sitting out there! . . .

Most likely, this salesperson will continue in this vein until the manager is persuaded that things are O.K. And most likely, that won't be too difficult, because managers want to believe. Optimistic forecasts from the sales force, as noted earlier, permit the sales manager to make his or her own forecast more optimistic. And - on the downside - asking a salesperson to leave is likely to cause disruption, distract the sales manager from more important tasks at hand, and perhaps reflect poorly on the manager.

We've presented these two dialogues in part to underscore the critical importance of having a process and managing to it. Discipline and structure are as important to sales as they are to basketball, military maneuvers, and the opera. Yes, creativity and spontaneity have their place - but not in a conversation between a salesperson and a manager of a publicly traded company about what opportunities make up the revenue forecast.

By reviewing progress (or lack thereof) against defined and auditable best practices, managers can assess the probability of winning a particular opportunity, and help salespeople do something that they are loathe to do themselves - that is, withdraw from low-probability opportunities. (For a salesperson, removing a low-probability account from the forecast generally means that a replacement will have to be found by prospecting, which is an activity that many salespeople like less than a root canal.) The role of salespeople is to build pipeline by executing the sales process; the role of the manager is to grade that pipeline, with an eye toward disqualifying. Managers should own the quality of the opportunities they allow their salespeople to spend time and resources on.

By invoking and sticking to a strong sales process, managers should be able to increase the percentage of winnable situations in the pipeline.

More Than One Process

A common misconception is that companies have a single sales process. In fact, most organizations have multiple offerings, serve different vertical industries, and engage in several different types of sales. Some examples include

Add-on business with an existing client

Sale of professional services

Renewal of a maintenance agreement

Sale to a prospect

Sale involving a partner

Sale through a reseller

Major account

National account

Given this diversity of transactions, many companies find that one size (or process) does not and cannot fit all of their selling situations. We suggest defining customer-focused steps and deliverables for your most complex sale, and then determining subsets of steps and deliverables for smaller transactions.

Targeted Conversations

In our view, a sales cycle can be distilled into a series of conversations between the seller and the buyer(s) for each defined step in a sales process. But the emphasis is on the buyer - that is, someone who is qualified and empowered to buy. This means that conversations have to be targeted. Sales-Primed Communications involves defining the titles or functions of people within a prospect whom salespeople will have to call on in order to get their proposed offering sold and installed.

Once those titles have been identified, a menu of business issues for each title should be developed. As explained in our previous discussions, a buying cycle does not begin unless or until the buyer shares a goal that your offering can help them achieve. Once you have a title and a business objective, you are in a position to have a targeted conversation.

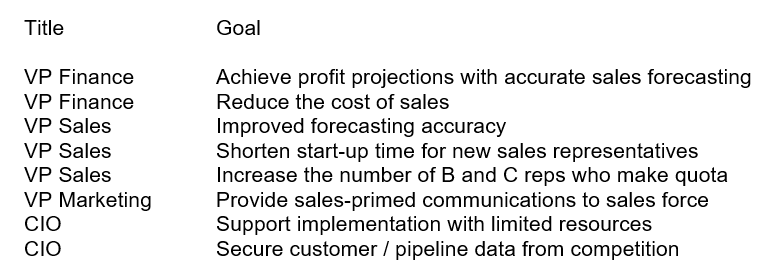

See the Targeted Conversations examples in Figure 5-1. This simply lists four titles at a prospect company and assigns a total of eight goals to them. Obvious? Perhaps. But we've seen most salespeople start making sales calls without this kind of structured and focused approach.

Another advantage of developing this kind of list is that it can include inputs from more than just the salespeople. In fact, people at many levels in the selling organization can contribute. In addition, targeting conversations permits a more consistent positioning of offerings, because the responsibility for positioning no longer falls solely on the shoulders of the salespeople. And finally, we find that targeting conversations tends to push conversations up higher in the hierarchy - and the higher in the organization a salesperson calls, the shorter the potential menu of business issues, the more predictable the ensuing conversation, and the more likely the sale.

Figure 5-1: Integrating Marketing and Sales Targeted Conversations for Selling: Sales Force Automation

The Wired versus the Unwired

Here's a piece of traditional sales wisdom: "Winners never quit, and quitters never win."

Nonsense. We believe that most organizations don't quit often enough, or early enough, when the odds are against them. Without a defined sales process, they don't know that the odds are against them.

Consider the case where a firm receives a "wired" request for proposal (RFP) that requests responses from ten vendors, and a sales manager authorizes the 60 hours needed (by multiple people) to prepare a response. (By wired, we mean that the fix is on, and the process is not truly open.) Would you agree that the salesperson who generated the initial interest, and shaped the RFP's requirements with a bias toward his or her own organization's strengths, has a 90-plus percent probability of getting the work? We would.

Now let's say that six other organizations choose to respond. What probability will the salespeople from those six firms enter on their respective forecasts? In most cases, the win rate on unsolicited RFPs is less than 5 percent. But if a salesperson were honest and assigned a 5 percent probability to this effort, his manager would almost certainly ask why 60 hours should be spent in crafting such a careful response to such a low-percentage opportunity.

Experienced salespeople skirt this issue by assigning even the wildest long shots at least a 50 percent probability. If you think about it, being a salesperson is one of the most measurable jobs in the world (percentage of quota obtained), but one of the least accountable. The 60 hours are spent, and when the order goes somewhere else, that opportunity quietly falls off the radar screen. In this example, even though only one favorable decision could possibly be made, six organizations within the vendor community have acted as if they all had at least a fifty-fifty chance at getting the contract.

This points out the fact that in defining your sales process, it may make sense for your organization to define two RFP processes. One should be for RFPs that your company has proactively uncovered and driven. A second one could be defined for RFPs in which you have been mainly reactive - that is, not well positioned to influence any of the requirements in the RFP prior to your receiving it.

To give you an idea of win percentages: We worked with a company selling enterprise software that had an entire department that did nothing but respond to RFPs. The previous year, they had reviewed their records and divided RFPs into proactive and reactive initiation. They discovered that in 1 year they had responded to 143 unsolicited RFPs that required an average of 75 hours - and got the business a grand total of three times! Long story short: Responding to RFPs that you did not initiate can be a huge drain on your resources. Consider segmenting your sales process, and investing your limited resources where they'll give you the most return.

Further Segmentation Opportunities

For companies having multiple divisions with independent sales forces, and / or those using value-added resellers (VAR's), it may be helpful to take a step back and decide who you want calling, and where. While this seems fundamental, sales organizations tend to evolve over time, and they sometimes get out of touch with a changing reality. A fresh look - a "clean sheet of paper" approach - can be helpful in stepping away from the trees and looking at the forest.

One account we worked with sold engineering software, and over time had developed an extensive reseller channel. They shared with us their desire to migrate their direct sales force from departmental technical sales to Fortune 1000 enterprise sales. After better understanding their direction, we attempted to segment their territories and markets and how they were being covered. We ultimately came up with a grid (see Chapter 17 and Figure 17-1) with the key demarcations they wanted:

Sales below $10,000 should be handled by their Telesales group.

Transactions with F1000 companies should be sold by their direct sales force.

Transactions with non-F1000 companies below $50,000 should be done by resellers.

Non-F1000 transactions over $50,000 should be handled jointly.

After defining these thresholds and where they wanted people to be calling, we asked the firm's sales executives what their coverage looked like currently. They sheepishly admitted that they had the small company/ small transaction quadrant covered jointly, transactions over $50,000 with small companies were rare, and virtually none of their direct salespeople were capable of executing an enterprise sale to the F1000. Further investigation uncovered the roots of the problem:

Their traditional salespeople were comfortable leading with product and talking to engineers, but were unable to relate to business people.

Their compensation plan provided an override on business sold by resellers in the direct salesperson territories. Some direct salespeople were making a great living by doing nothing more than overseeing the efforts of their assigned partners, and hadn't closed any business of their own in over a year.

The executives realized that in order to achieve the desired coverage, it would be necessary to train their salespeople to make higher-level calls, and that the compensation plan had to change. Due to their concern about the potential loss of many of their direct salespeople, we suggested a 12-month weaning period, during which the override would be phased out. This approach allowed the pipeline on larger accounts to be built. Turnover was minimal, and a high percentage of direct salespeople who were either unable or unwilling to make the adjustment to large account enterprise sales voluntarily joined reseller organizations - a favorable outcome for all concerned.

This situation was discussed, and an approach to resolving it was completed, in about an hour. We don't claim to be geniuses, and in fact, none of the concepts came close to being rocket science. But we think the example underscores the fact that most sales processes evolve over time and that a fresh look is often a good idea. (And in many cases, inviting in an outsider for a new perspective turns out to be productive.)

The Clean Sheet of Paper

When it comes to sales process, an occasional "clean sheet of paper" look is a good idea.

Take, for example, a company that starts with a few salespeople and co-founders selling the first few accounts, then evolves into a $250 million organization using both direct and indirect sales. The VP of Sales was the first salesperson hired all those years ago. A wonderful success story, all around - and yet, in our experience, the company could derive a great deal of benefit from a third party facilitating a session to evaluate (1) where the business is heading, (2) what markets they are attempting to penetrate, and (3) who is calling where.

Just as offerings, markets, and sales situations are dynamic, sales processes, too, must be reviewed and adjusted on an ongoing basis, if they are to reflect how your salespeople sell. A review is advisable, and milestones should be either verified or modified by analyzing the results. This may be done as often as quarterly, for a relatively new market or offering, or on an annual basis for mature organizations.

As suggested above, consider reviewing your top five wins to highlight best practices in selling. And as unpleasant a task as it may be, review your toughest five losses as well, in an attempt to see if your process needs to be changed.

Process Is Structure

Our view is that a sales process represents the management team's best understanding of how buying cycles take place, and how to fit into those cycles.

As with most processes involving human behavior, there can and will be exceptions that must be made under certain circumstances. While some sales methodologies treat selling situations as being black or white, experience has taught us there are many, many shades of gray.

If the potential usages of your offerings are highly variable (i.e., consulting, professional services), process becomes more important. The worst-case scenario is a salesperson calling on a buyer who has a wide spectrum of responses and reactions without a plan of how to handle the call. In one sense, sales process tries to put structure around the number of sales calls made during a sales cycle.

Without sales process, every situation is an exception based on the seller's opinions. Despite the potential benefit of repetition, everything gets done "once in a row." This can be costly at several levels:

Salespeople are determining when and how to compete. These are people whose compensation is based on gross revenue, without regard for the amount of resources required either to win or to lose. Their qualification skills in filtering out low-probability opportunities tend to be proportional to their year-to-date quota positions. For someone behind quota who is working marginal opportunities, things are likely to get worse, not better.

Without putting structure around sales situations, selling organizations lack the ability to drill down and better understand the kinds of circumstances that are likely to result in unsuccessful sales cycles - or, conversely, are likely to lead to sales.

CEOs frequently proclaim to the investment community that their firms embody "best practices." Unfortunately, we rarely hear this claim made in regard to sales - probably because most companies don't do so, and wouldn't dare to claim to. In fact, when it comes to sales, they're not even sure that best practices exist. (It's an art, right?)

We believe that a milestone-based road map that can be audited is absolutely essential. Sales is less an art, and more a craft. While the design and implementation of an effective sales process are formidable tasks, the upside - having better control over top-line revenue generation - can be absolutely invaluable.