Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 9: Marketing's Role in Demand Creation

In previous chapters, we've been advocates for a new psychological stance for Marketing. Marketing, we've said, should think of itself as being the front end of the sales process, instead of the back end of the product-development process. Why? Because we believe that this is a prerequisite for more closely coordinating efforts with Sales.

Marketing is a huge function, and it comprises many activities that are beyond the scope of this resource. So as we look at Marketing's role in demand creation, let's explicitly limit our scope. We intend to focus on Marketing's direct support of salespeople by attempting to create demand for qualified buyers to generate leads and move new opportunities into salespeople's funnels. We will not look, for example, at Marketing's efforts to build brand recognition and awareness or its strategic planning for future offerings.

Leads and Prospects

Most Marketing departments allocate a large part of their budget to creating demand for their offerings, in one way or another. In some of those organizations, salespeople are not expected to do much heavy lifting as relates to prospecting or business development. In such cases, they are dependent on leads, a nebulous term that reflects (1) the poorly defined relationship between Sales and Marketing and (2) a lack of understanding about what a good prospect is.

Let's start with this second issue. Does your company approach demand creation systematically? If so, are you learning enough from your customer base to leverage how they've used your offerings to achieve goals, solve problems, or satisfy needs?

Here's an exercise you might want to try. Figure out, in rough terms, the entire potential of your territory, district, region, or total target market. By potential, we mean the total number of people or entities that could benefit from using your offerings. Once you've established that figure, estimate what percentage of the people or organizations in that universe are currently conducting evaluations for offerings comparable to yours.

What do we mean by an evaluation? Here are five important criteria that suggest that a legitimate evaluation is underway:

The buyers have identified a business goal they want to achieve or a problem they want to solve that you believe can be addressed by your offering.

One or more decision makers are involved.

Requirements are documented.

A buying decision will be made within your average sell cycle.

Budget for the project has been earmarked.

As they conduct this exercise, most vendors conclude that only a small percentage of their potential prospects meet these criteria. (Most people find that between 0 and 10 percent of their potential market are currently evaluating.) In other words, there aren't many legitimate evaluations going on out there.

At the same time, though, they discover something very interesting: The majority of prospects that are not actively evaluating have goals that are similar to those of the prospects who are. This begs the question: Why would a buyer not attempt to improve an important business variable? Our experience suggests that there are three common answers:

The company or buyer is unaware that it is possible to improve the business variable.

The company or buyer is aware that the variable could be improved, but doesn't consider it to be a priority (including a budgetary priority).

The company or buyer failed in previous attempts to achieve the goal, and is reluctant to try again.

So if the vast majority of your targeted marketplace is not looking to change, that's bad news, right? Yes and no. It's bad news if your organization knows only how to be reactive. But it may be good news if your organization knows how to be proactive - that is, how to cause buyers to begin considering change. Two advantages come to mind immediately:

There is a huge, untapped pool of prospects out there.

If you help initiate an evaluation, there's every chance that if the buyer ultimately considers other alternatives, you will be "Column A" - the vendor whose offering is perceived from the outset as the best match with the requirements of the buyer, and therefore is the standard against which other competitors are measured.

Many salespeople believe the best way to build a pipeline is to find and pursue active evaluations. Why? They are qualified in that budget, perceived need, and timeframe have already been established. We suggest that the real marketing challenge is to target potential decision makers (people who can spend or allocate unbudgeted funds) who are not looking to change with your Sales-Primed Communications. If you disagree, please keep an open mind while reading further.

The Bottom Line on Budgets

Having already singled out salespeople, many companies steer their salespeople toward finding opportunities where buyers already have active evaluations underway. They do that by making budget an early qualification question that sales managers ask.

Is that smart? Let's examine why companies have budgets, and what salespeople can learn from the budgeting process.

Let's first agree why budgets are a way of life for buyers and sellers: Senior executives must predict and deliver a bottom line to investors. The two major variables are top-line revenue, which is speculative, and spending, which is more controllable.

Going into a fiscal year, would it be prudent for a chief financial officer to give, say, the top 20 executives in the company permission to spend whatever they felt was necessary to run their functions within the business? If he or she did so, it is possible that toward the end of the first quarter, it would turn out that each manager had spent $1 million more than what was expected. The CFO would then have the unpleasant task of informing the chief executive officer that the company was $20 million over on the spending side - which would in turn mean that the CEO would have to alert investors that earnings projections were not likely to be achieved. So budgets are established to control the expenditures of people within the organization, and to allow the CEO and CFO to sleep at night.

If given the choice between reporting missed earnings due to a revenue shortfall or due to a budget overage, most CEOs would opt for the former (and in a heartbeat). Even the most hard-nosed analysts and investors recognize that the CEO exerts only a tenuous control over revenue generation. These same people, however, would view the failure to control spending as a sign of gross executive incompetence.

That's the theory: Budgets are set at the beginning of the year and are cast in stone, and everybody sleeps well. The reality, though, is very different. In real life, companies retain a great deal of control over how they will spend their money, month-to-month or week-to-week. If a compelling case can be made that expending unbudgeted funds will (1) increase top-line revenues by (significantly) more than the cost of the outlay or (2) cut costs to a similar degree, most companies can find the necessary funds.

So - to bring this back to the perspective of the salesperson - if a buyer claims not to have budget, so long as the target organization doesn't have insurmountable financial or other constraints, the salesperson and manager should conclude that he or she is not calling high enough within the prospect organization.

Here's a real-life example from our own experience of how funds can be freed up for unbudgeted expenditures: A vice president (VP) of Sales told us that he wanted to conduct an internal workshop for his staff, but he couldn't authorize the funds. He asked us to do an executive overview of our methodology for his VP of Marketing, his CFO, and his CEO. This entailed a flight to Utah, so we agreed to do the overview if he would defray our travel expenses, which he agreed to do. (Quid pro quo in action.)

Near the end of our discussion, the CEO asked how much it would cost to implement a sales process in his company. Because he already had a vision of how the process could be used and the accompanying value, we reviewed pricing with him.

After discussing costs, the CEO turned to his CFO, Ed, and asked how the company's cash flow looked. Ed gave the answer that all good CFOs give when asked that question in front of a salesperson: "Things are a bit tight." The CEO turned to the VP of Marketing. "Caroline," he asked, "of the three trade shows we plan to participate in this year, which one provides us the least value?" She quickly identified the laggard. On the spot, with the concurrence of his colleagues, the CEO decided to skip that trade show, thereby freeing up funds for the sales-training program. The CEO told us to work out the details and contact him with any questions, and then left the meeting.

In other words, when you call on decision makers, budget alone does not prevent buyers from going forward. Having said that, of course, even the most senior decision makers can't print money, so if they set a new priority, it is likely that some other project may have to be deferred or cancelled. This is part of the reason so many buying cycles wind up with no decision.

So salespeople not only compete with other vendors, they also compete for "mindshare" of business executives who have to decide how best to invest their company's limited capital, and how to adjust allocations that have - in most cases - already been fought for through the previous budgeting cycle.

Starting Out as Column B

We've already alluded to the advantages of starting out as Column A - that is, of being the vendor whose offering is perceived from the outset as the best match with the requirements of the buyer.

We believe salespeople who are called into or stumble on opportunities where buyers already have budget for the project should assume that they are not Column A. (The vendor who has initiated the evaluation that led to this opportunity is Column A, and will continue to enjoy this position unless or until another vendor is able to change the buyer's requirements.) In creating demand, therefore, we believe it is vitally important to cause organizations that are not currently looking to change to start looking to change.

Let's examine how much better your chances are as Column A versus Columns B, C, D, and so on, the inhabitants of which we sometimes refer to as "silver medal" vendors. Have you ever noticed that only one vendor gets the order (gold medal)? The other four are told: "We liked your proposal best, but I'm sorry to tell you we awarded the business to another vendor. You came in second." Here is a scenario that may be familiar:

A salesperson sits at her desk, debating whether to work on overdue expense reports or make some cold prospecting calls, when the phone rings. A prospect in her territory begins the call:

I'm Ray Jones, project manager for XYZ Company. The reason for my call is that we are going to make a buying decision within the next month. I already have budget approval for the project. We've heard good reports about your company and products and would like to give you a shot at earning our business. We'll need a demonstration, price quotation, references, and a proposal as soon as possible. You should be aware that this ultimately is my decision, so there's no point in looking for ways to go around me. How soon can we meet to discuss these items?

In the wake of this kind of call, most traditional salespeople would feel fortunate to have been invited to compete for the business. The appointment would be scheduled for the earliest possible time, the salesperson's manager would be informed that there was a "hot one" in the funnel, and this opportunity would appear on the salesperson's next forecast. The pricing, references, demonstration, and proposal would be expedited to meet the prospect's tight timeframe. Everyone in the selling organization would be feeling a little giddy.

Before we allow ourselves to get too excited, however, let's examine the sequence of events that most likely preceded the call's being placed to the salesperson. (This is a composite, based on lots of stories like this that we've heard.) Is this a hot prospect?

Six months ago, Salesperson A uncovered a requirement for a product that XYZ Company had never considered, which meant that no budget had been established for this purpose. The sales cycle started at a lower level within the organization. After months of effort and education, a base of support and an overwhelming business case was built for Salesperson A's product, which cost $100,000. The internal champion could see the value of buying the product, but needed to obtain approval for an unbudgeted expenditure.

After the business case and an attractive payback were presented, the CFO said: "You've put a lot of effort into this evaluation, and it sure looks as though the benefits far outweigh the costs. What other vendors have you looked at?" The internal champion answered, truthfully, that no other alternatives had been considered. "Well," the CFO continued, "our corporate policy is never to consider just one vendor for a purchase of this magnitude. Get other quotes so we can make product and pricing comparisons. And by the way, please don't bring any salespeople in to meet with me. How soon can you perform this analysis and get back to me?"

After this meeting, the internal champion at XYZ Company has a sense of urgency about completing the requested analysis. To get funds allocated, he must perform due diligence by considering other options. But how objective will his evaluation really be? Naturally enough, he wants his initial vendor recommendation to be the chosen alternative. After all, Salesperson A initiated the sales cycle, showed strong potential payback, and spent months developing a relationship. The internal champion may confess to Salesperson A that he is required to look at other vendors, and solicit her advice on which ones to consider. What he may not fully understand is that Salesperson A also anticipated that her prospect would be instructed to look at competitors, and has prewired (biased) the requirements list to play to her product's strengths.

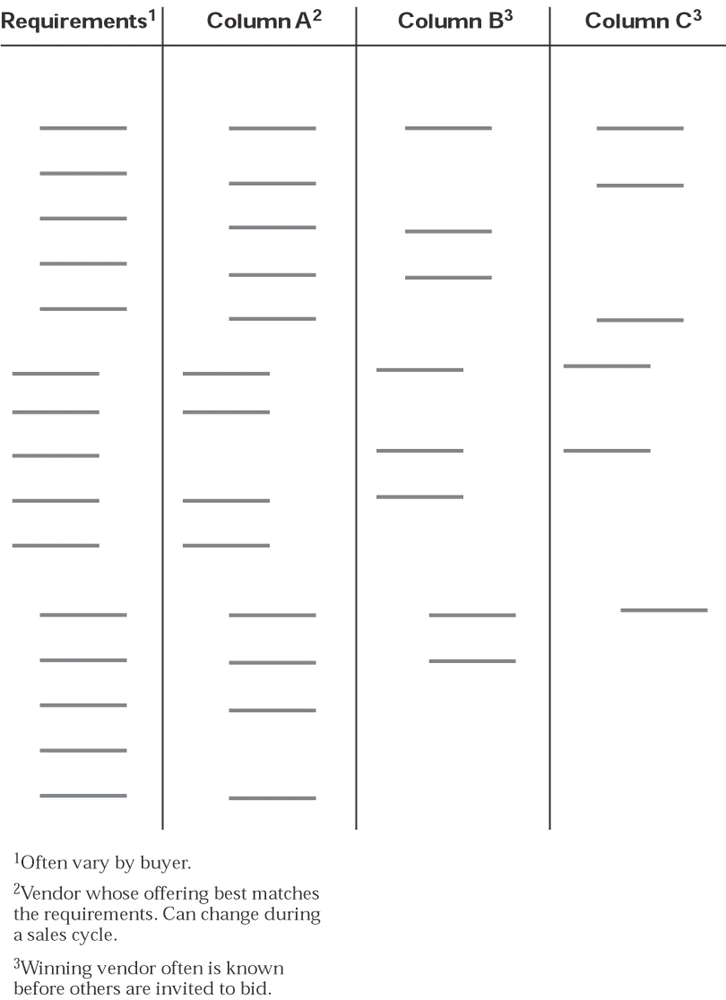

What does this list (see Figure 9-1) look like? The requirements column on the left is filled out first: a detailed description of the only product that has been evaluated to date. Column A is just to the right of this column. It is filled in completely, and - not surprisingly - it is more or less an exact restatement of the requirements column. To the right of Column A are blank columns for Competitors B, C, and D to fill out. The internal champion is now ready to call and invite the silver medalist candidates to bid on the business, provided they can pull all the numbers together by the deadline.

Figure 9-1: Vendor Evaluation

How well will the competitors compare? If Salesperson A's product is price-competitive, Competitors B, C, and D have little chance of getting the business. If Salespeople B, C, and D ask for the opportunity to meet the CFO - who could potentially change the requirements - they will be denied that opportunity. Even if one of them were successful in adding new features to the requirements list, weighting factors could still be used to ensure that Column A would win. If a lower bid comes in, Salesperson A may be given a clandestine opportunity to sharpen her pencil after all quotes are received. In other words, Competitors B, C, and D have been invited to compete, lose, and ultimately help the internal champion do business with the vendor he wanted from the start. In most cases, the reward for Columns B, C, and D is the silver medal.

Column A's internal champion next schedules a follow-up meeting with the CFO. Although multiple alternatives are shown, there is a clear choice. Reallocated money for Column A is approved. Vendors B, C, and D are thanked for their responsiveness, complimented on doing an excellent job, and told that it was a difficult decision, but that they were not chosen this time. All three are told that they came in second, and that if future requirements arise, they'll be invited to bid. The losing vendors remove XYZ Company from their forecasts as a competitive loss, feeling - correctly, in many cases - that they could have turned the situation around, if only they had gotten into the account sooner.

In short: When you are told early in a sales cycle that the budget has been approved, you should always assume that your competition has set the criteria. The prospect has already started to evaluate the merits of comparable products or services being offered, and has obtained cost estimates. If this were not the case, how could they possibly know already how much money to budget?

Being called by prospects with preapproved budgets and tight deadlines for providing demonstrations, pricing, references, and proposals should warn you that you are being asked to provide a column. If the answer to the question, "Is there a budget?" is yes, sales managers may want to ask an additional question: "Whose numbers did the prospect use for obtaining budget approval?"

In our client engagements, we try to get our audiences focused on the advantages of being Column A, as opposed to being silver medalists. One way we do so is to ask them to look back on the competitions they've won over time, and to estimate the percentage of those wins that represented situations in which they started as Column A.

Most people wind up giving a number in the 80 percent range. Flipped the other way around, this means that they have a 400 percent better chance of success if they can proactively cause people to look to change. Yes, individual salespeople should prospect to fill their funnels, but Marketing also has a critical role to play as the front end of the sales process.

It should be noted here that the perceived average sales cycle for a company could be misleading. Even if you are calling high, when you are Column A, a fair amount of time is needed to get to the point of having a closable order. When you are coming in as a potential silver medalist, the good news is that it will be a short sell cycle (Column A has already done most of the selling). The bad news is that the sales cycle is likely to have an unhappy ending.

Marketing and Leads

If you want to start a buying cycle where none exists already, it is necessary to get mindshare. With decision makers, as suggested in previous chapters, this will not usually be accomplished by leading with your offerings. What we suggest, instead, is leading with business issues to generate curiosity and interest. Leading with business issues offers organizations the benefit of higher entry points into prospect organizations, leading to shorter sales cycles and quicker access to mainstream-market buyers because the buyers are now being shown product usage or potential results rather than starting with your offerings.

Which issues? Well, let's revisit the Targeted Conversations List - containing a menu of goals by offering, vertical industry, and title - that we created in the previous chapter. Using that tool, we would now like to offer a definition of a lead that Sales and Marketing can agree on, because the three components of a lead are the same as the Targeted Conversations List:

Vertical industry

Title (or function)

Business goal identified

In our model, an organization (or salesperson) cannot begin selling until a Targeted Conversation buyer expresses a goal that can be achieved or a problem that can be addressed with an offering. When that happens, you have a legitimate lead that Sales and Marketing can agree is qualified. For companies with no standard definition for a lead, how meaningful is the process of tracking close rates?

We'd now like to discuss the various avenues that most marketing groups currently use in an attempt to generate interest - brochures and collateral, trade shows, seminars, web sites, and so on - and how these approaches can be improved (by leading with either business goals or business problems) or replaced.

Brochures and Collateral

Just as traditional salespeople feel compelled to "spray and pray" when contacting prospects, so do most brochures and collateral literature. Many are little more than product specifications, often with some graphics and a sampling of nebulous terms (seamless, robust, synergistic, leading edge, and the like) thrown in to make them slightly more readable.

But this is silly. When you go fishing, you choose a specific location, type of bait, type of hook, and method (trolling, casting, and so on), all based on the particular type of fish you are attempting to catch, right? Why would you not do as much, or more, when trolling for prospects?

Here's a useful exercise: Pick up a piece of collateral that is likely to be sent to a prospect, and turn the pages. As you do, ask yourself:

What level within the organization would want to read this?

Can this level allocate unbudgeted funds?

What business issues does the collateral attempt to raise?

What action is it intended to prompt?

Yes, there is always a role for strong technical information - but is it something you want to lead with, in attempting to get an entry point into a prospect organization? In most cases, the answer is no. Brochures with extensive technical detail are best at (1) answering a deep question from an expert, (2) informing those who are not decision makers about your offerings, and (3) reinforcing credibility that you've built up in other ways.

Another generally deadly approach is to provide traditional salespeople with glossy "pocket folders," that is, large folders into which smaller brochures, letters, and business cards are inserted. In many cases, when a prospect asks, "Can you send me some information?" traditional salespeople start emptying out their drawers of printed material. The result? Five dollars in printing out the door and a three-dollar charge for the mailing, at the end of which buyers feel that they have received too much information (TMI) and therefore don't read much (or any) of the material. (We hear this story all the time as we follow up on clients' salespeople.) This, in turn, prompts the classic response from the prospect's assistant: "I'm sure she's seen it, and if there is any interest, she'll get back to you."

We don't recommend putting this prospect on your forecast. Does it belong there?

Of course, Marketing can reduce this exposure to some extent by being selective about the types of collateral it produces. But in addition, we suggest that when they receive requests for information, salespeople respond by asking for a brief discussion to better understand the buyer's area of interest, so that they can send only material that is germane. It doesn't hurt to be explicit about this: "We have lots of offerings with different capabilities, and we'd prefer not to subject you to saturation bombing. What, exactly, do you want to know about?" Another alternative is to ask the buyer: "What are you hoping to accomplish?"

Here are some possible alternatives to spec sheets and too many brochures falling out of pocket folders:

Menus of business goals or problems

Success Stories

Sample cost-benefit results achieved by customers

Note that the menus of business goals or problems can be taken directly from a Targeted Conversations List, as described in the last chapter. The point of the menu approach, of course, is to allow sellers to use examples of common business problems to lead the buyer into a discussion. It's often easier for the buyer to say, "Hey - we have this same problem!" than to say, "Let me describe this odd problem we, and only we, seem to be having."

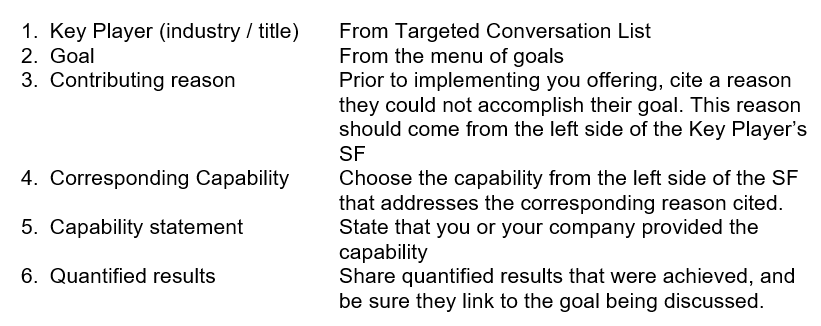

Success Stories are one of the oldest techniques in the sales profession. For understandable reasons, buyers are much more comfortable if they are not among the first to buy the seller's offering. Keeping in mind the concept of product usage and Targeted Conversations, consider the Customer Focused Sales Success Story format in Figure 9-2.

Note that the first two components (Key Player and Goal) are from a Targeted Conversations List. Once a seller gets a buyer to share a goal, the next element is a "contributing reason" for the customer's not being able to achieve the goal. This reason is naturally aligned with a capability. The benefit statement now allows the seller to finally say, "We gave him that capability," and then finishes with the actual benefit derived from the customer's use of the offering.

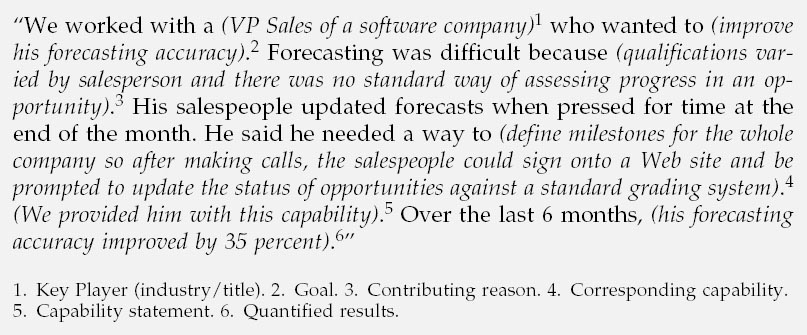

In Figure 9-3, we have reproduced an actual Customer Focused Sales client Success Story. This particular client sells a host of manufacturing productivity-enhancing products and services, and the Key Player and goal are from their Targeted Conversations List. The contributing reason is aligned with one of their key capabilities: early warning notifications. After their salesperson delivers a benefit statement, she can then finish by quantifying the actual financial benefit.

Note that this Success Story was crafted by Marketing, published by Marketing, used by the Training department in training salespeople, and finally used by the salespeople when engaging potential new prospects. This is the kind of collaboration that leads to sales success.

Figure 9-2: Success Story Components

The third alternative to the standard collaterals listed above is sample cost-benefit results achieved by customers. These can be extremely powerful tools, because they let customers speak to customers, without any intermediation by the salesperson.

Figure 9-3: Establishing Credibility: The Success Story

Trade Shows

By now, it should be clear that we don't approve of vendors leading with offerings. So you can guess how we feel about the ways in which many vendors - especially technology vendors - display their wares at trade shows. Product, feature; product, feature; product, feature; and so on. Suffice it to say that there's almost always room for improvement. The exception, of course, may arise in the case of an early-market offering, where just putting your product in front of early-market buyers - and letting them figure out how to use it - may be a valid short-term approach to getting help in understanding how your offering can help a buyer achieve a goal, solve a problem, or satisfy a need.

But let's assume that you're not pursuing Innovators and Early Adopters. So first things first: Exactly what are you trying to accomplish by participating in a trade show? Are you trying to generate leads? Many Marketing departments pound their chests in triumph after a trade show generates 500 "bingo cards" requesting information. But the hapless salespeople who follow up on these so-called leads soon discover that 95-plus percent of them are dead ends. They turn out to be consultants just trying to pick their brains, college students interested in the technology or looking for employment opportunities, window shoppers, trinket gatherers, and so on - in other words, people who may be intrigued by your offering, but can't buy.

If you were to take the total cost of participating in the trade show (including all personnel) and divide by the number of bingo cards generated, you might be shocked at how expensive these leads are - especially in light of the fact that many or most are not leads at all. And it gets worse: According to Gartner Group, a face-to-face call by a high-tech salesperson costs over $400, when all costs are taken into account. So if you called on just one in five of those 500 bingo-card contacts, you'd be out another $40,000!

Remember, too, that your initial contact becomes your point of entry into an organization. In the case of an enterprise sale, entering at the user level almost guarantees a long sell cycle. You'll probably spend a lot of time, along the way, with people who can't say yes, but can say no.

We suggest taking a different approach to trade shows. Just as companies can differentiate themselves with a sales process, we believe they can do the same with trade shows. When seeking mainstream-market buyers, consider scaling back your participation in traditional trade shows. Choose shows that business people are more likely to attend.

Get a small booth, and resist the temptation to load it up with equipment. Use prominently displayed quotes, or likely menus of goals or problems, to get Targeted Conversation attendees (who are not necessarily thinking about change) to slow down, enter your booth, and share a business goal. This puts your staff in a position to begin asking intelligent questions that the prospect is able and willing to answer.

If demos are appropriate, we suggest asking interested prospects if they'd like to see the offering. If they agree, fill out a card with (1) their goal and (2) the capabilities they'd like to see. Direct them to a suite away from the floor, where they can have refreshments and make phone calls. When they're ready, they visit the suite and give the card to one of your staff, who can then tailor the demo to the specific capabilities the buyer is interested in seeing.

Seminars

In a newly assigned territory, or in the case of a new announcement, a seminar can be an effective way to jump-start pipelines. Seminars take time and effort to coordinate, but they provide an opportunity to sell one-to-many, and therefore should not be overlooked. So the goal should be to structure them in a way that provides maximum benefit. Again, the ultimate goal here - as with the tools and techniques suggested above - is to get buyers who were not looking to change to realize the potential benefits of change, and initiate an evaluation. Your prospect pool gets bigger, and you're in Column A.

An important first step is to bring together a group of attendees who have something significant in common; for example, they work in the same industry, or do more or less the same job. A good way to do this is to feature one of your customers - preferably from a familiar company - who holds the same position and is willing to share a problem that your offering has helped them solve. When it works, this is a win-win-win: Your customer is flattered, the attendees can readily relate to material presented by someone with credibility who speaks their language, and you get access to a pool of prospects.

Little things count for a lot. Schedule your seminar for first thing in the morning - before people go into the office - and limit it to between 1 and 2 hours. Prepare your invitation carefully: It is very important in laying out the agenda and setting expectations. If you hope to attract an executive audience, spend enough money on invitations so that it looks like an executive event.

Consider preparing a menu of goals or problems that are likely to be relevant to this target audience, and include that menu - and a preaddressed envelope - along with the invitation. Encourage them to highlight topics that they would like to have covered during the session. (You may want to post this menu on your web site as well, so that invitees can do their highlighting electronically.) You can tabulate the results in advance of the seminar, and thereby maximize your alignment with the audience.

Follow-up is just as important as the invitation - and maybe even more so. Call the people you've invited, and ask if they plan to attend, if they have looked at the menu, and if they have any questions that you can address. Above all, see if you can get them to commit. Then be sure to call the day before - under the pretense of getting head counts for refreshments - and confirm that they still plan to attend. You don't want a half-empty room, and sometimes it's worth making a full room (of high-potential people) the responsibility of one of your more reliable and creative people.

Start the session with a brief overview of your company - no more than 5 minutes, tops. If you were able to collect and pretabulate the menu of business issues before the meeting, present them now. Otherwise, build a menu on a flip chart by asking for suggestions, and then use that menu to settle on two or three goals that are of general interest. (Assure your guests that concerns that are not dealt with at this session can be revisited one-on-one at a later date.) In some cases, you may want to use a Success Story to prime the pump. Or, you may want to survey the entire room to pin down common reasons why attendees can't achieve the results they are looking for. After the session, you may have demos set up (if appropriate) that are focused on the specific capabilities that were discussed and presented.

Your objective, again, is to get them looking to change. We don't believe that one-on-one selling is appropriate at seminars. On the other hand, if you can get a business card and an associated goal or objective, this sets the stage for a follow-up phone call or meeting that can quickly determine if there is an opportunity to pursue.

Advertising

In too many cases, advertising ignores the most basic rule of Customer Focused Sales. It treats offerings as nouns, instead of verbs. It ignores or undervalues business issues as a way of generating interest.

While the subject of advertising is large enough to justify volumes all on its own, let us suggest two Customer-Focused approaches for advertising:

Attempt to create "results envy" by having buyers realize that people in their own industry, and with the same job function, are achieving improved results through the use of your offerings.

Use a "hurt and rescue" approach, getting people to realize that there is a business problem that they are now experiencing, and that they have a means to control it.

In all cases, try to focus on the action you want buyers to take as a result of seeing your ad. Options would include, for example, visiting your web site, calling a toll-free number, contacting a local office, sending in a response card, and so on.

Web Sites

We don't have to belabor the obvious: When it comes to the internet, the bloom is off the rose. The widely shared expectation that web sites would be able to sell anything to anyone, 24/7, has been brought crashing to earth by mediocre results. True, an ever-increasing amount of buying takes place on the internet, but very little selling (or need development) actually goes on. Most web sites are nothing more than electronic brochures. They lead with product, and they treat it as if it were a noun. In fact, it's difficult even to point to a model "selling" web site.

What went wrong? It has a lot to do with the evolution of the relevant technologies. web sites began as one-dimensional and static, mainly because of the limitations of modem speeds and twisted-pair capacities. Interactivity was a far-off dream. With the advent of high-speed Internet connections, these barriers have been overcome for many applications. A recent development, product configurators, can lead potential buyers step-by-step to a purchase recommendation - in other words, through a crudely interactive process.

So although technology has eliminated many barriers, the interactions still tend to be plodding and mechanical. We have yet to see a web site that begins to simulate the work of a Customer-Focused salesperson. Perhaps it's unfair to expect a machine to interact with a person as well as another person would, especially since computers are still largely limited to seeing the world in a binary, on/off way. But web sites do hold the potential to have dialogues with buyers, and we think they should begin to live up to that potential.

The Solution Formulator described in previous chapters is all about dialogues, based on "conversation architecture." There's no inherent reason why this kind of architecture can't be recreated in the context of the internet. Given adequate investments in programming, a web site should be able to discover the interests of the internet visitor and, based on those interests, present content in a sequence that simulates a sales call.

We remain optimistic. Think how far these technologies have come in less than 2 decades. Even with today's technologies, we believe, it should be possible to build a web site capable of developing a visitor's vision, either to qualify a buyer or - depending on the type of offering and expense - to take a sale all the way to closure. With tomorrow's technologies, it should be far easier.

Letters, Faxes, and Emails

These can be effective ways to create demand, either on a companywide basis or within a salesperson's territory. If best practices are going to be shared companywide, Marketing should provide a readily accessible inventory of sales-ready messages that are industry and title specific, so that individuals are not reinventing the wheel. Let us defer this discussion until the next chapter, where we'll focus on prospecting efforts within an individual territory.

Redefining Marketing's Role in Demand Creation

To summarize: Marketing can play a critical role in creating demand for a company's offerings. If Marketing is going to serve as the front end of sales cycles, then its messages across all media should be consistent with the salesperson behavior we espouse: namely, leading with business issues with people who can make decisions and allocated unbudgeted funds.

Marketing should be the keeper of Sales-Primed Communications, but should not be expected to accomplish this in a vacuum. Sales should provide constructive input, continuing to fine tune material so that it reflects best practices in the field.

Marketing and Sales have to agree on the definition of a lead. We submit that a legitimate lead contains three components:

Vertical industry

Title

Goal

There are only a certain number of people out there who are already looking to change. Chances are, they already have a preferred vendor in mind. Demand generation entails causing people who weren't looking to change to begin a buying cycle. This segment represents many times the potential number of people who are already looking, and offers the advantage of allowing salespeople to be proactive and become Column A, instead of being reactive and competing for a silver medal.

People who are not already looking to change have no budget allocated, so the focus in those organizations should be on people who have the authority to free up unbudgeted funds. And, as always, we strongly recommended leading with business issues and usage, rather than the traditional "spray and pray" approach.

As we have seen, Customer Focused Sales cannot begin until buyers share either a business goal or a problem that a vendor's offering can help them address. Whether you are designing advertising campaigns, participating in trade shows, or putting on seminars, you should begin with the end in mind: creating qualified leads for the sales organization.

In summary, few companies have a working definition of the interrelationship between Sales and Marketing. Companies implementing Customer Focused Selling embrace the following description of each function's role:

Marketing, through its programs, is responsible for getting buyers who are not currently looking to change to consider looking. Marketing is also the keeper of the tools needed to take a businessperson from a goal to a vision of a solution.

Salespeople execute the sales process using Sales-Primed Communications. In doing so, they are responsible for documenting calls so that sales managers can audit and grade the opportunities in the pipeline.