Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 13: Negotiating and Managing a Sequence of Events

Overview

In this chapter, we'll look at the challenge of transforming the sell cycle from a realm of mystery - which is how some buyers and sellers view it - into a rational and orderly process.

But first, to introduce the subject, let's imagine that a salesperson has worked on a major opportunity for 4 months. Let's imagine further that a Customer Focused Sales consultant is hired to analyze each opportunity in the pipeline, and the consultant asks the salesperson to estimate when this particular opportunity will close. For the purposes of this example, let's assume the Customer Focused Sales consultant knows the decision maker on this transaction, and can ask him or her to provide a date when the sale can be made. What is the likelihood that the buyer's date will be later than the seller's date?

A few observations:

Most closing is driven by the agenda of the sales organization, with little or no regard for the buyer. Many organizations that are under pressure to meet monthly, quarterly, or annual targets resort to "blitzes" to bring in business, based on those internal pressures.

The vast majority of closing occurs before the salesperson has earned the right to ask for the business. When salespeople attempt to close orders before buyers are ready, they run the risk of being perceived as a traditional pushy salesperson - or, worse, of scaring the buyer off entirely.

If a salesperson closes before a buyer is ready, discounting is the most common method of giving the buyer a reason to sign early. In these premature efforts to close, a great deal of negotiating is done with non-decision makers. This can be demeaning for buyers who can't commit. In some instances, the discount offered to non-decision makers becomes the starting point for the real negotiations.

In our consulting, we will ask clients, "How can you know when a transaction is closable?" There is almost always a prolonged silence, as people realize that this question is not readily answerable with their current approach.

In fact, many organizations (buyers and sellers) view sell cycles as random series of events that sometimes result in orders. Salespeople push buyers to go through sales cycles without gaining consensus or commitment. Many salespeople do not ask for, and therefore fail to get, access to the people within the prospect organization who will be required to sell, fund, and implement the recommended solution. How many "opportunities" in your current pipeline have at least one documented buyer goal?

Just as a competent chess player thinks several moves ahead, salespeople should do the same as they attempt to facilitate the buying process. Despite the fact that every sale appears to be unique, based on the size of the transaction and the size of the prospect organization, there are many common steps in the buying process that have a high probability of recurring.

By agreeing to and adhering to a clear Sequence of Events, the salesperson provides documentation that allows sales management to continue auditing and grading opportunities. Like the qualifying efforts described in the previous chapter, this removes overoptimistic opinions from the forecast, and minimizes the phenomenon of salespeople "selling" their managers on how good their pipeline is. When they make their forecasts, sales managers should have the benefit of a piece of paper that shows a planned Sequence of Events for each potential sale, and what progress has been made in that sequence.

By documenting sales efforts and gaining commitment to sequences of events, sales managers can play a vital role in deciding what deserves to be in each pipeline. As soon as an opportunity does not look winnable, the sales manager should brainstorm with the salesperson as to how to change the landscape of the decision. If the two of them together are unable to figure out a way to do this, they should withdraw from the opportunity. The alternative is hanging in there with a high probability of being one of several silver medalists.

When documented by means of a clearly stated Sequence of Events, the process of controlling a sales cycle begins to resemble project management. The decision process embedded in a sales cycle has a defined beginning and end, and - as noted above - the selling organization has the ability to assess progress and probabilities of success throughout.

There's also an ancillary benefit: When the seller handles sales cycles in a highly professional manner, buyers are likely to conclude that the selling organization's implementation will be professional, as well. This perception can allow buyers to feel more comfortable with a given company, and especially with a relatively untested company selling complex offerings. We believe salespeople and the companies they represent can make the way they sell a competitive advantage and a differentiator.

Getting the Commitment

The first step, of course, is getting the commitment from the buying organization to move forward with the evaluation of the offering.

As noted in the previous chapter, we believe that prior to committing to a buying cycle, salespeople should meet with all Key Players to understand their issues, determine if their offering represents a fit for the buyer's environment, establish potential value, and gain consensus that a formal evaluation makes sense. Key Players should understand what's in it for them. They should then come to some consensus and agreement on (1) the steps needed to reach a decision and (2) the timeframe for the overall evaluation.

Now it's time to move the process forward. To do so, the salesperson has to orchestrate getting all the key people together. This is the meeting that, in the previous chapter, you invited the chief financial officer to attend. The seller has to summarize progress to date and verify that the buyers feel there is enough potential benefit that further investigation is warranted. Finally - and most important - the seller has to obtain a commitment to proceed.

At some point in this process, the seller may attempt to push toward a commitment by pointing out a fact that should be obvious, but often isn't: By taking the time to evaluate this particular offering, the buyer is making a serious commitment of time, resources, and effort. Yes, the seller has a lot at stake, but the buyer, too, has money on the table, and that pile of chips is only growing. (Of course, the seller can be prepared to point out the cost to the buyer of not moving, as well.)

Looking for a commitment benefits the selling organization in several ways. First, it continues the qualification process. (If this opportunity is going to fizzle, let's find out sooner, rather than later.) Second, the selling organization wants to shape the sales cycle as much as possible. Simply put, would you rather sign a lease prepared by your landlord, or one prepared by you?

Looking for a commitment doesn't always succeed. A salesperson selling enterprise software recently told us about his attempts to obtain agreement on a $100,000 opportunity that he was working on. The VP of Engineering and the CIO were in favor of committing the resources necessary to work with the vendor. The VP of Manufacturing, though, had a track record of having difficulty with implementing technology, and was known to be a potential Adversary. Sure enough, during the meeting designed to gain consensus, the whole deal came unraveled, as the VP of Manufacturing argued passionately, and ultimately succeeded in convincing everyone, that it was "not the right time" to consider new software.

So is our recommendation - scheduling a meeting to extract a commitment from the organization - a bad idea? We don't think so, because we believe that in sales, bad news early is actually good news. Would you rather learn that the "opportunity" is a pipe(line?) dream in month 1, or in month 6, after you have expended a great deal of time and resources, and have been carrying it on your forecast as having a high probability of closing?

Keeping Committees on Track

After obtaining consensus from the committee that the value of the potential solution warrants further investigation, there is a great chance to begin qualifying the opportunity. The first thing the salesperson should ask the committee is what they would like to see in order to evaluate the offering. This will usually elicit requests for demonstrations, site surveys, proposals, and so on. These are things that will take a sales organization a great deal of time and effort. Conservative mainstream-market buyers are also apt to ask for things a salesperson does not want (or lacks the authority) to commit to. Examples would be a money back guarantee, a lengthy free trial with no exposure, and the like. While early in a company's history salespeople may have to make concessions, as the offering matures and an installed base has been established, these requests become unreasonable. How does a salesperson respond?

One option is to take them head on, potentially responding, "We would never be willing to do that for you." In light of the fact that you've just gotten consensus to continue with considering your offerings, this represents an inopportune time to take such a hard stance. Keep in mind that you have a decision maker or makers with their subordinates in a meeting. It is likely that the senior executive wants to flex his or her muscles on a salesperson. An alternative is to merely acknowledge you've heard the request without agreeing or disagreeing.

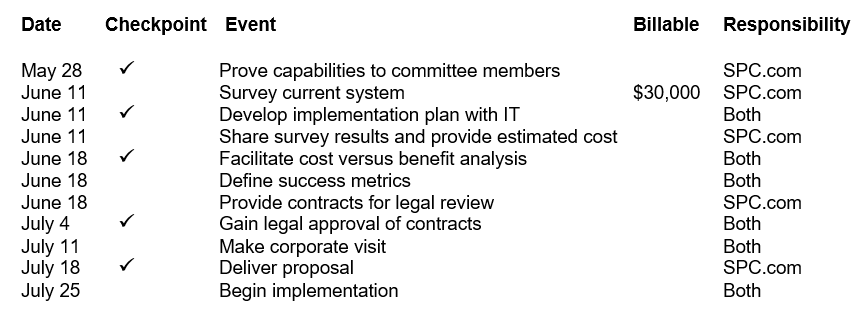

Once the prospect has had an opportunity to respond to what the management would like to see in order to evaluate your offerings, the salesperson now has a chance to share an example of a Sequence of Events template showing typical steps previous buyers have taken on the way to making a decision on the offerings. Hopefully, this can serve as an outline for a final agreement on the steps and an approximate timeframe for the buyer's arriving at a decision. A sample is shown in Figure 13-1.

The salesperson can end the meeting by disarming any misconceptions in the event the committee has asked for things that he or she cannot commit to by thanking everyone for their time and indicating he or she will take the list back to the office and propose what he or she feels is the best way to proceed. If it is clear there is a single decision maker, the suggestion would be to commit to sending a draft copy to that person for review. After that step, any necessary changes could be made prior to copying the other members of the buying committee.

After negotiating the internal resources the company is willing to commit, the salesperson can send a cover letter and draft copy of the Sequence of Events. A phone call or meeting to follow up should be scheduled with the decision maker, to ensure that the person has had a chance to review the document. The salesperson will then ask what, if any, changes are necessary. At this stage, any unreasonable requests (i.e., a money back guarantee) would be notable by their absence in the draft of the Sequence of Events. This means one of two things will happen. One possibility is that the buyer will not raise that point, in which case you can proceed. The other would be for the decision maker to challenge the fact that the money back guarantee was not offered.

The salesperson could then ask the reason for wanting a guarantee. It is likely that the buyer will explain that it is to mitigate risks associated with the decision. At this stage, the salesperson (if this is not one of your very first customers) could respond that because fifty-three other companies have already implemented this application, the company would not be in a position to offer a guarantee, but the prospect can visit one of the company's customers who has already successfully implemented. If the buyer insists on a guarantee, the salesperson may have to determine if this is a showstopper, in which case the buying cycle may come to a grinding halt. While this is not the desired result, most would agree that it is better to find out now rather than at the end of the sales cycle. Bad news early is good news.

When the salesperson calls to follow up, it is a bad sign for a decision maker to agree to the Sequence of Events without requesting changes. This would be a sign that either the document hadn't been reviewed or the prospect was taking the commitment lightly. The correct response is to change dates or challenge some items. Your objective is to be able to remove the word DRAFT from the document, but it is most effective if the buyer makes changes because then he or she takes some ownership in the buying cycle. Some of our clients purposely leave some dates blank so the buyer is forced to make changes.

Gaining Visibility and Control of Sales Cycles

In any event, if and when the Sequence of Events has been successfully negotiated with the decision maker, we suggest that at that point all committee members should be copied with the Sequence of Events. Both buyer and seller now have an agreed-on approach to making a buying decision. Buyers find it comforting (and unusual) to be working with a salesperson who has already thought to ask about and negotiate the steps leading to a buying decision. At this point, the seller has gotten agreement from the committee for the approximate duration of the sales cycle.

As for controlling the buying cycle, both the buyer and seller share veto power at each checkpoint. That is to say, each of these steps represents an opportunity for either party to withdraw from the evaluation.

Why Would Either Party Withdraw?

Consider for a moment the potential reasons a buying committee would elect to withdraw from a negotiated evaluation: a change in priorities, an acquisition, a reorganization, insufficient payback on the proposed project, references don't check out, investigation shows the offering not to be a good fit, and so on.

Now brace yourself as we begin to list reasons for a vendor to elect to withdraw from an ongoing Sequence of Events. Some traditional salespeople cannot begin to fathom any circumstances that would make them effectively remove an opportunity from their pipeline. Here are some potential reasons for a vendor to withdraw: Customer expectations may be unreasonable, the offering may not be a good fit, the transaction may not be profitable, a review may show that the prospect is not creditworthy, and so on.

While all these reasons are valid, the best reason to withdraw is that you realize the opportunity is not winnable. The manager who wants the sales staff to compete to win, not to keep busy, usually must make this decision. As soon as you believe you are not Column A and you cannot change the requirements list, it's time to find a different opportunity to work on. Traditional salespeople, wanting to hang in until the end (and keep their pipelines inflated), sometimes have to be forcibly removed from the "prospect."

Most typically, the Sequence of Events will serve as a road map, but will tend to be a living document. That is to say, about once a month it may need to be republished to reflect any alterations that need to be made either to the events or to the timing of events. Once this process is in place, sales managers enjoy several potential benefits:

They can coach salespeople through the process step by step.

Planning for allocation of resources can be done.

Each checkpoint the buyer agrees to further validates the buyer's commitment and increases the likelihood of a successful completion.

Sales managers have the ability to assess (disqualify) opportunities if they do not appear to be winnable.

It is unlikely that buyers looking for Column B, C, or D would commit to a Sequence of Events with a silver medalist.

It is far easier to forecast close dates because buyers have agreed to tentative dates for delivery of a proposal and a decision. This helps take vendors away from the tendency to close based on their agendas.

Negotiating the sales cycle also addresses a problem that virtually all salespeople face: not knowing when an opportunity is closable. Our belief is that the right time to close is when a Sequence of Events has been completed to the buyers' satisfaction and the seller's satisfaction. Our clients learn that each step in the Sequence of Events is a miniature close and that asking for or getting the order is a logical conclusion.

While we are on the subject of buying cycles, one of the most frightening situations occurs when a mainstream-market buyer is being asked to commit to a large expenditure (let's say $500,000) for an application that has never been implemented before. Many Key Players consider the potential impact on their careers if the anticipated results aren't achieved. The Sequence of Events can be used to mitigate risk by providing a "pay as we progress" approach. By this we mean that the $500,000 expenditure can be broken into smaller pieces (feasibility study, preliminary design, prototype, and so on) that are billable events. After each, both the buyer and seller assess where they stand and make a determination as to whether to proceed.

Reframing the Concept of Selling

Earlier, we articulated our desire to reframe the concept of selling as helping a buyer achieve a goal, solve a problem, or satisfy a need. This definition applies to the buyer-seller relationship. At a higher level, we believe that the Sequence of Events approach empowers our clients to extend this philosophy to a company-to-company perspective. Negotiating the steps in the buying cycle enables all committee members (the prospect organization) and all members of the selling organization to be on board with the stated objective of determining if the offerings can satisfy the overall needs of the prospect. As soon as this doesn't appear to be possible, either party can opt out of expending further resources.

Mainstream-Market Buyers

In previous chapters, we described the phenomenon of mainstream-market buyers. Sales cycles with these buyers most often move at a slower pace than those involving early-market buyers. These mainstream-market decisions are almost invariably made by committees consisting of several people, with the majority of them having the ability to scuttle the project by saying no, but lacking the authority to say yes. Mainstream-market buyers are often governed by one or both of the following principles:

They are looking, but they lack a strong commitment to buy. Salespeople in these situations may begin throwing resources at the opportunity, hoping that the right thing will happen. In these cases, they run the risk of providing free education. These can be relatively easy situations for mainstream-market buyers to be involved in because the vendors do virtually all of the work as the buyer is getting exposure to new approaches. Unless compelling reasons to act can be uncovered by the salesperson, the result may well be no decision. The most common reasons for this result are

The salesperson never negotiated a Sequence of Events with all Key Players.

Business goals or problems were never identified.

The buyer did not fully understand what he or she was buying or how it would be used.

There was no compelling benefit versus cost.

The buying committee was concerned about the staff's ability to implement the recommendation.

If, for some reason, a mainstream-market buyer gets serious about making a decision, it is a virtual guarantee that the buyer will shop the transaction around by talking with other companies offering similar products. In some cases, if there are no comparable offerings in the market, the buying decision will come to a screeching halt. Mainstream-market buyers want to compare offerings from at least two or three different companies. Doing so may verify in their minds that it is too early to risk going ahead with the project. They are likely to postpone a decision unless or until the offering gets to a point where multiple companies are in that space and the offering shows the potential to become the de facto standard.

Assuming that there are alternatives, mainstream-market buyers will feel compelled to invite at least three companies to assess their needs and make a recommendation. We refer to this process as "running a beauty contest." While it is an advantage to have been the vendor that caused the sales cycle to begin (Column A), many unfavorable things can begin to take place. Despite the fact that a start-up company has a superior offering, mainstream-market buyers are apt to evaluate more established companies. Even if the seller has inferior offerings, doing business with a known corporate entity potentially lowers exposure to risk and second guessing if the project fails to meet expectations. Within the technology sector, for years IBM was seldom thought to have the latest or least expensive offerings. IBM did, however, represent the safest choice. Many transactions were won by appearing to be the safer alternative. At times, inviting two or three different companies to present their offerings will confuse mainstream-market buyers, which always have "no decision" lurking in the background if things get overwhelming.