Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 16: Assessing and Developing Salespeople

Overview

On at least an annual basis, most Human Resources (HR) departments require sales managers to formally assess their staff. And despite the fact that the sales manager should have reviewed twelve (or more?) forecasts from each salesperson over the course of those 12 months, it can be a tough job to sit down and formally analyze what has transpired in a year.

Consider the following outstanding, average, and difficult performance reviews, which are composites from our experience working with salespeople over the years.

Salesperson A, Mary, consistently achieves 200-plus percent of quota. The manager invites Mary into his office, and begins

Mary, it is difficult to put into words what a pleasure it is to have you on my team. Thanks for your contributions over the past year. I've filled out your evaluation, so take a minute to review it and ask any questions you may have. (Mary spends 2 minutes reading the glowing evaluation and has no questions.) Well, then, this will go into your personnel file. I'm pleased to give you the maximum 5 percent raise on your base salary. Let me know if there is anything I can do to help you going forward. At this stage, my inclination is to just get out of your way and let you sell. Congratulations on a tremendous year!

Salesperson B, whom we'll call Joe, struggles to make his numbers. Two of the last three years he has made quota (as he did last year) by a few percentage points. He achieved 92 percent of quota 2 years ago. He enters the office and hears:

Joe, let's review your performance evaluation. Take a few minutes to look at it, and then we can talk. (Joe sees several areas where he is considered average. There are a few areas showing his skills to be above average, balanced by areas needing improvement. It is a fair assessment that accurately points out his strengths and weaknesses.) Joe, I hope you agree with my assessment and comments. Overall, I'm glad to have you on the team, but I wish you could increase activity within your pipeline. If you were to increase prospecting activity, I think you could . . . (The discussion drones on for about 30 minutes, including comments about skill sets that must be "shored up," interspersed with compliments about strengths. The meeting grinds to a conclusion as Joe signs the evaluation.) Joe, I hope this session was worthwhile. I want you to strive to increase activity and make your numbers by the end of October. Won't it be nice for us to be able to enjoy the holiday season at the end of this year? I've put in for a 2 percent raise in your base. Let's make this the year that you knock the fences down.

Keith, Salesperson C, finished the past year below 50 percent of quota, and is sitting at about 50 percent of quota year-to-date halfway through the year. This review promises to be difficult:

Keith, why don't you come in and take a seat. (The manager rests his chin on both hands, effectively covering much of his face, and starts to talk.) Keith, Keith, Keith, this has been a rough couple of years for both of us. Do you see things getting any better? (Keith mumbles a vague, uninspiring answer.) Well, based on your performance over the past 18 months, we have two choices. One is for HR to get involved. We would put you on a performance improvement plan and give you a 90-day period to get year-to-date against your quota. It would necessitate weekly meetings and mounds of paperwork. If after 90 days you still weren't tracking to your numbers, I'd have to terminate you. Do you think that you can close that much business in the next 3 months? (Again, Keith's answer fails to inspire confidence.)

Look, Keith, I know you have a family, and candidly, I'd hate to have to terminate you. Off the record, we could look at things another way. If you feel you can't make your numbers, the next 90 days could be put to a different use. I won't be taking attendance, so you'd have time to explore other options. Most people find it is easier to find a job while they have one. Why don't you sleep on it, and let me know how you'd like to proceed. In the meantime, don't tell anyone we had this conversation. Maybe a fresh start at another company is just the thing you need to get your career on track. Let me know what you decide.

Sound familiar? Anyone who has managed salespeople has faced these situations. (And maybe you've even been Mary, Joe, or Keith at some point in your career.) Mary is a customer-focused seller who neither wants nor needs to be managed, and will consistently produce. Joe is typical of traditional salespeople, who constitute the majority of sales forces. Every year, making quota is an adventure, and one that typically goes right to the end of the year. Keith's situation is a nightmare for everyone. He may be unskilled, unlucky, or lazy. Most likely he'll be working for another company within the next few months, regardless of whether he opts for the performance improvement plan or immediately begins a job search.

The reviews presented above are typical of those received by salespeople who have not been supported by Sales-Primed Communications and a sales process. The traditional sales manager knows what he or she is doing, in terms of traditional methods of motivating the sales force; he or she also seems to have a pretty good sense of the salespeople. But it's certainly fair to ask: Is this the first time that Joe has heard that he needs to improve? How long has Keith been bumping along on the bottom without intervention from above? Can either Mary or her manager articulate what makes her a customer-focused superstar?

In this chapter, we want to introduce a sales management process to assess and develop salespeople.

Golf Is Easier

The title Sales Manager is misleading. We believe a manager's primary responsibility is to develop people. The reality is that most traditional sales managers - including the one in our example above - are administrators attempting to drive numbers. They tell their direct reports what to do and in what quantity, but are unable to teach them how to do it. Sales managers have many different modes; they may try to motivate, intimidate, nurture, mentor, and so on. They finally admit defeat when their mode switches to counseling people out of the business.

But more often than not, the issue is not one of motivation. Most underperforming salespeople sincerely want to do better, but lack the necessary skills. All the encouragement, incentive programs, and intimidation in the world can't teach a salesperson to sell. If Keith is intelligent and motivated - which, after all, was part of the hiring model - then having him do more of what he's already doing is unlikely to get him to improve his performance.

As noted in an earlier chapter, most sales managers got their jobs because they were naturally talented salespeople. They don't necessarily understand how or why they were successful, yet they are now charged with passing their intuitive selling skills onto their direct reports. The path many sales managers in this situation take to get salespeople up to speed is osmosis: "Watch how I sell, and learn (because I can't describe it)." Often intense during the first month or so after a new hire signs on, this kind of "training" tends to fall off precipitously shortly thereafter. The sales manager has other things to do - there's another new hire that needs the benefit of osmosis.

On balance, skill-transfer results using osmosis are disappointing. Osmosis is a poor substitute for sales process. And without process, selling resembles an art more than a science.

Assessing and coaching skills without understanding the basic mechanics of selling is next to impossible. When professional athletes experience slumps, there are standard ways of identifying and correcting the problem. A professional golfer, for example, has several ways to identify swing flaws and correct them. First, there are generally accepted mechanics associated with a golf swing (head down, left arm straight, and so on). The golfer in question may view videos of a sound golf swing (either his or her own, or that of another player). Many have a "swing coach" who works with them. Even the process of identifying the problem - a problem on which the golfer and the coach can agree - gives rise to a surge of hope: This problem can be fixed! And this, in turn, gives the needed motivation to spend all that time on the driving range and playing practice rounds.

Is there a sales equivalent to the golf story? The answer is, "There should be, but it's hard to find." Consider a salesperson whose performance was previously at acceptable levels, but has been in the doldrums for the past year and a half. Some harsh realities:

There are few generally accepted and useful rules of selling. There are general notions: listen, don't lead with product, selling begins when buyers say no, always be closing, and so forth. Some of these we subscribe to, and others we take issue with. Our motivation with this process is that there was nothing close to a useful road map of how to sell, especially when compared to an activity such as hitting a golf ball.

Selling habits have been developed through an unstructured series of individual trial-and-error experiences. Instead of good "muscle memory," the salesperson has bad muscle memory, and self-diagnosis becomes extremely difficult. This makes it virtually impossible for someone to coach a salesperson out of a slump. As previously mentioned, Neil Rackham discovered that as sellers become more familiar with their offerings, they begin to lose patience and empathy in asking questions and listening to their buyers. This behavior is virtually impossible to self-diagnose.

There is no "practice range" for salespeople. If a golfer hits several bad shots on the driving range, ego aside, there are no negative consequences. In fact, it may help in isolating flaws. But salespeople have no "range" on which to experiment. They are under pressure to produce numbers (more so when they are in a slump), and they do not have the luxury of trying new approaches without potential consequences. A poor call reduces the number of prospects in the finite territory by one - and, in practical terms, for the duration of the salesperson's current employment.

As relates to development and improvement, salespeople live on remote islands. One of the biggest challenges comes when the salesperson disagrees with his or her manager about a given course of action. There is no surge of hope like that experienced by the golfer and the coach. Slumping salespeople must work their way out of it alone. The sales manager is likely to make the problem worse if he or she applies pressure by demanding increased levels of activity (i.e., quantity) without influencing the quality of activity. Most people's performance degrades under pressure.

Assessment: What Doesn't Work

Sales management without sales process is largely a forensic (after-the-fact) exercise. Managers perform silver medal autopsies after losses and during annual HR reviews. They wind up not helping either Joe or Keith, and - most likely - firing Keith or persuading him to move on.

But imagine if managers could be proactive instead of reactive. Proactive steps - corrective surgery - could reduce the need for autopsies. Why does it take a loss (or nagging from HR) for managers to act? We believe it is because most sales managers are merely driving numbers. Lacking the ability to assess and develop their people, they assess and develop their people's numbers, instead. But this is exactly backward. If sales managers could develop their people, the numbers would take care of themselves.

First, let's look at flaws in the assessment process. Let's assume the annual evaluation requires sales managers to rank salespeople as one of the following overall categories (we've added our editorial counterpoint in italics):

Exceptional salesperson who consistently exceeds quota and provides leadership to the office. Displays outstanding knowledge of offerings, possesses strong administrative skills, exhibits strong account control, and shows ability to disqualify poor opportunities from his or her funnel. Requires minimal guidance, and is a candidate for promotion into sales management.

Sales management would be a breeze if these people could be cloned.

Steady performer who meets or exceeds quota the majority of the time. Has a tendency to work identified opportunities and grow ongoing accounts. Sometimes gets entangled in low-probability opportunities. A more aggressive business development plan and more structured approach could bring performance up to the next level.

Sales managers are happy to have people like this on the team. They need occasional coaching, but by and large they can be trusted with small to medium opportunities.

Struggles to keep activity levels to a point where the pipeline reaches targeted levels. Requires extensive coaching, and requires managers to make joint calls whenever feasible. Needs extensive support on all opportunities and coaching on a weekly basis.

This had better be a new hire on the way to becoming a 2. If he or she doesn't show progress within the next year, though, there will be a tough decision to make.

Has difficulty generating meaningful activity in territory. Marginal understanding of both offerings and industries called on. Micromanagement is necessary, both in reviewing activity from the previous week and in planning activity for the following week.

Unless dramatic improvement is realized in the short term, it appears that either a hiring error has been made or the salesperson's skill or motivation has eroded. Unless things change, a performance improvement plan or termination looms on the horizon.

Selling is one of the strangest professions. Performance is measured exactly - sometimes to within hundredths of a percentage point. Companies calculate commissions to the penny. Many companies require managers to assign a single grade to reflect their assessment of a salesperson's perceived skill set that can influence his or her career path. But in reality, is this precision? Can a single grade reflect the skill set and abilities of a salesperson? We believe the answer is no.

Taken collectively, the skill set and personal characteristics required to consistently exceed quota are staggering. We know renowned doctors, lawyers, and professors who would starve as salespeople: They just don't have what it takes. For a complex offering, we believe a salesperson needs a minimum IQ of 120, strong verbal and written skills, the courage and confidence to accept a position where only a portion of his or her compensation is guaranteed, and so on. So can a sales manager effectively rate someone like this on a scale of 1 to 4? Not likely.

Performance Does Not Always Mean Skill Mastery

Let's assume that Ron was the third salesperson hired by a start-up company that is now publicly traded and has revenues of $150 million. Ron was involved in the initial large sale to an early-market buyer 8 years ago. This sale validated the company's offering, and he received extensive support in that sales effort from the founder and other senior executives. For the past several years, Ron has averaged 225 percent of quota, largely by handling the growing requirements of three major customers. Ron's last cold prospecting call was made several years ago, when the thin condition of his pipeline drove him to make a call.

Ron has achieved legendary status, and preferential treatment, within the company. People wonder why he has never gone into management. The answer is simple: Ron has realized that his personal strengths and his quality-of-life goals all indicate that sales is the best position for him.

Ron's manager treads lightly and consistently grades him as a 1. Failing to do so would probably prompt a call by Ron to the CEO complaining about his manager and the review, and necessitate changing the grade on the evaluation in Human Resources' file.

According to his annual reviews, Ron is a 1 in the areas of need development, account management, negotiating, qualification and control, and so on. Peeling back the onion, however, it turns out that he is not a 1 in the skill of business development and prospecting - in fact, he is a 4. At this stage, it is impossible to tell if the problem lies in skill (cannot) or attitude (will not). In any event, Ron's manager is not doing him a favor by ignoring this glaring deficiency. Ron is, in effect, coasting. Smart salespeople know intuitively that they are worth what they can earn in their next sales position. If for some reason things go south with this company, Ron may face the challenge of finding and accepting a territory with a company where he does not enjoy sacred cow status and most likely will not be given the largest installed accounts to develop.

Seven Selling Skills

As shown in the previous chapter, sales managers can be proactive in analyzing pipelines so that activity levels can be increased. This approach helps the manager influence the quantity of activity. We'd now like to show a technique for upgrading the quality of activity. To do so, we've distilled selling into seven skills:

New business development

Solution development

Opportunity qualification and control

Proof management

Access to Key Players

Negotiation and closing

Monitoring success metrics

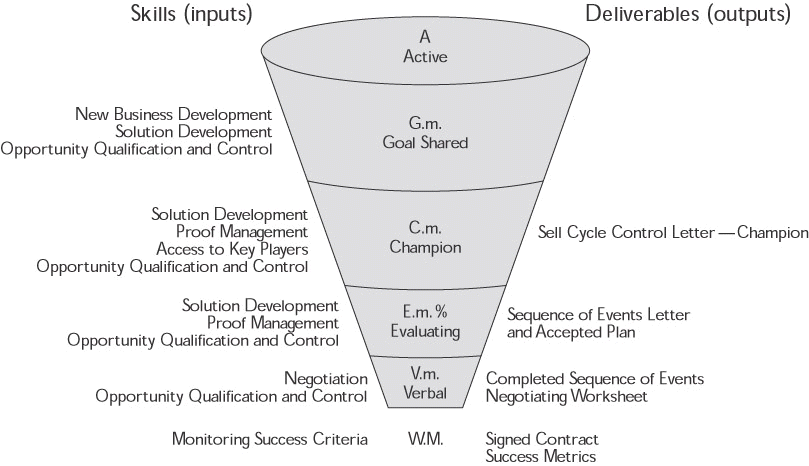

These skills tend to come into play at different times in the buying cycle, as shown on the left side of Figure 16-1. On the right side are the deliverables that a sales manager can monitor to assess the skills of each salesperson. A discussion of proof management and monitoring success metrics is beyond the scope of this resource.

Figure 16-1: Funnel Management: Skills and Deliverables

The shapes of funnels vary greatly by salesperson. The funnel of someone exhibiting high activity but low skill mastery in the area of business development could look like a martini glass, with many conversations (As) needed to generate Gs. As opportunities enter and progress through a salesperson's funnel over the space of a few months, if there are blockages where deals tend to stall, this points to a probable skill deficiency. We'd like to show how to assess funnel data so that skills can be assessed and - wherever necessary - the sales manager can come up with specific plans containing activities needed to shore up weaknesses.

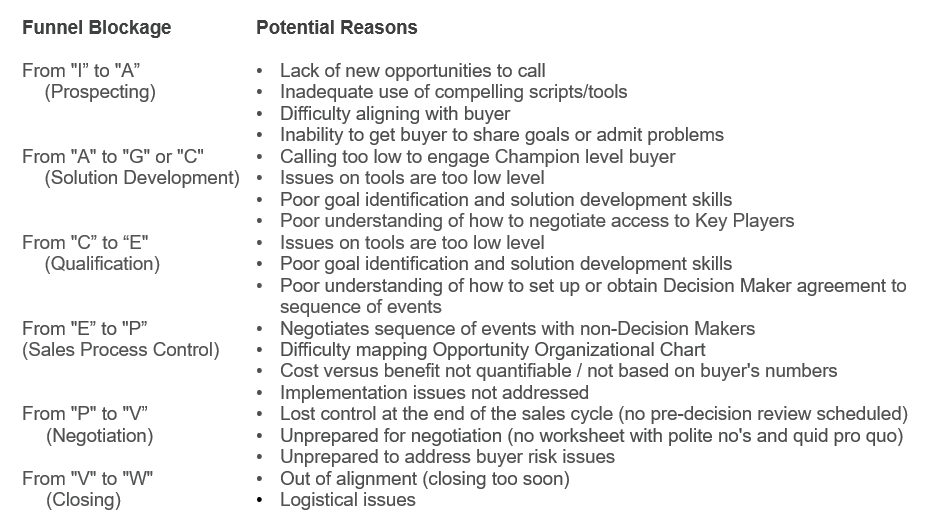

Let's now assume that over a period of 2 or 3 months, there are blockages in a salesperson's funnel - which, again, point to likely skill deficiencies. Look at Figure 16-2.

Figure 16-2: Analyzing Funnel Blockages

An insufficient number of As entering the funnel points toward a problem with business development. In response, the manager could set a minimum number of first contacts per week or month, but that would not address the quality of the effort. A proactive Customer-Focused sales manager would do the following:

Ask to see the letters, faxes, and emails that the salesperson is using to generate interest. It could be they are not worded properly, or are geared toward the wrong vertical industry or title. The manager could help write the documents and design a more effective strategy.

Ask the seller to spend some time with a peer who has realized great success in business development. It may be appropriate for the person who is struggling to listen to one of his or her peers making calls, or following up on leads, to see that person's approach.

The sales manager could role-play being a buyer taking a prospecting call from the seller.

Blockages in getting prospects from A to C would point toward a lack of skill in getting buyers to share goals. The manager could spend time reviewing the following areas:

Review the menu of goals for each Key Player that the seller is using.

Help the seller generate and use the Success Stories that take a buyer from a latent need to sharing a goal.

Role-play with the seller to walk him or her through approaches to getting goals shared or problems admitted.

If opportunities stall at G status, there are two areas that are likely to need addressing. The first is that the seller lacks the ability to take a buyer from goal to vision, meaning he or she is either not using the correct Solution Formulator (SF), or is having difficulty executing it. Again, the manager could review the material being used and could role-play with the seller. The manager could also make joint calls with the seller and demonstrate how to use the SF.

Another reason for stalling at G status can be that the seller has difficulty getting prospects to agree to Champion them and get them to the Key Players who need to be accessed. This difficulty can occur because the buyer's vision is not compelling (letters should be edited), there is not sufficient value in the mind of the buyer, or the seller is not able to defend or explain the need to meet with the Key Players requested. In such cases, the suggested approach would be to make joint calls - either face to face or via conference call. It is also possible that potential Champions are being offered proof without the seller's using a quid pro quo approach to getting access.

If a seller has opportunities that stall after qualifying a Champion, there are several potential areas of difficulty:

If most of his or her Champions are at relatively low levels, there may be difficulty relating to more senior executives. This skill can be developed via role-playing and making those executive calls jointly.

The seller may be having difficulty in gaining consensus and negotiating a Sequence of Events with the buying committee. The manager should have the seller take him or her to visit accounts where all Key Players have been met, but where no Sequence of Events has yet been finalized.

The seller may be attempting to qualify people at relatively low levels within organizations as Champions. As stated earlier, a salesperson's quality of life will be better if he or she can get decision maker level Champions. In such cases, access to Key Players is most often volunteered, rather than the salesperson's having to ask or negotiate for it.

Once an opportunity reaches E status, the seller and manager should have at least a 50 percent chance of having the sell cycle result in an order. In our opinion, the single most important variable in determining win rates is which seller initiated the opportunity (again, caused someone who wasn't looking to change, to look). Having an agreed-on plan in place affords the manager visibility into whether or not the opportunity is moving forward. By evaluating the status at each checkpoint, managers take some ownership of and responsibility for determining that the transaction is winnable. As soon as it appears that things are not proceeding as planned, the manager and seller should strategize as to how to get things back on track. And as always, in some instances, it will be necessary to withdraw. This should (will have to?) be the manager's call.

Leveraging Manager Experience

The manager has to make a judgment call as to whether the pace of progress is satisfactory. This is a complex decision that takes into account whether the seller is dealing with early- or mainstream-market buyers, the size of the organization, the size of the opportunity, and the overall impact or risk to the prospect in moving forward. Here are some warning signs to look for:

The buyer starts to push dates back.

Access to Key Players becomes more difficult.

Line items in the agreed-to Sequence of Events are challenged.

Buyer requirements change, potentially influenced by competitors.

A Key Player leaves or is reassigned.

When managers are trying to decide at a given checkpoint whether to continue to compete, there is one key bellwether question to consider: "Are we the vendor of choice for at least one of the Key Players - and if not, what can we do to get there?" If the ultimate answer is, "We can't get there," it may well be time to withdraw from the opportunity, rather than throwing time, effort, and resources into what is likely to be a losing cause, resulting in yet another silver medal.

Senior executives of sales organizations may want to monitor average discounting levels by district and salesperson to identify potential skill deficiencies in negotiating. A caution, though: If a potential problem is identified, it may not be the salesperson's. We worked with an organization that had a district manager in Boston who was a terrible negotiator. When he was brought in to help the seller on large transactions, the discounts offered wound up being far greater than those in other offices. (In fact, he had earned the nickname "Moon over Massachusetts" because of his propensity to discount.) For a period of time, his manager had to review and role-play the polite "no's" and get/gives prior to going to the negotiating meeting. There were a few instances where he had to walk prior to getting the business. Within 3 months, though, his discounting fell into the acceptable range.

Another statistic to track is the level of discounting based on the date of the order. Buyers expect the end of the month or quarter to give them better leverage in getting concessions. Whenever possible, an attempt should be made to schedule the Sequence of Events so that the decision date doesn't coincide with a quarter end.

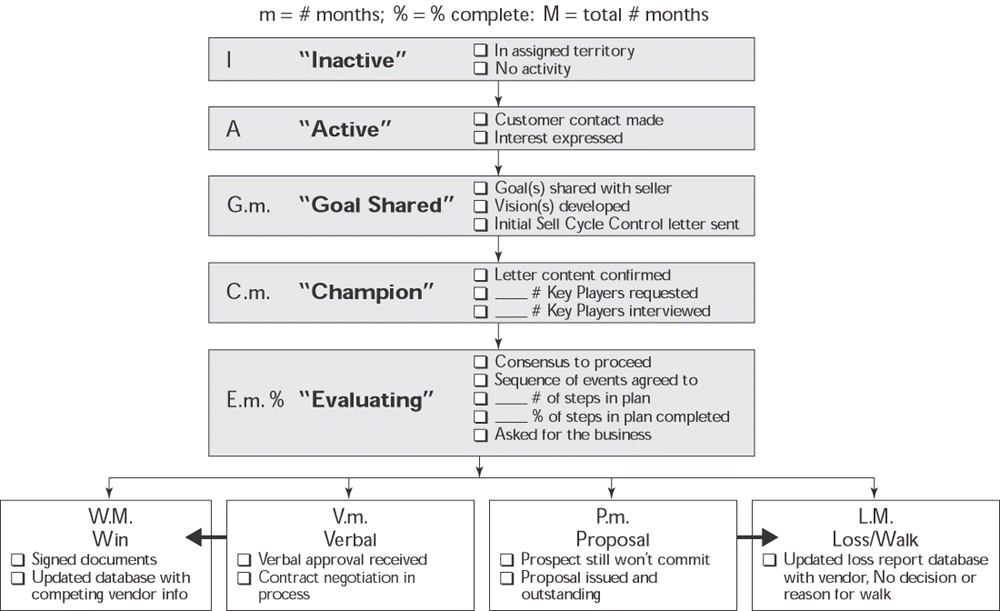

Once a seller has asked for the business, the opportunity goes from an E to one of four milestones. Look at Figure 16-3.

Figure 16-3: Grading Opportunities: Pipeline Milestones (m = no. of months; M = total no. of months; % = % complete)

W.M. |

The seller got the order. The capital M reflects the total number of months it took to win. An analysis of the length of winning sell cycles can be helpful in isolating best practices. (The most important single variable often turns out to be how high the entry level within the prospect was.) |

L.M. |

The seller loses, either to no decision or to a named vendor. Tracking and analyzing the total months of losses may isolate common events that lead to losses, so that hopefully they can be avoided in future sales cycles. |

V.m. |

The buyer has provided a verbal commitment, but for some reason the contract or purchase order cannot be issued. In such cases, we suggest asking the buyer to sign a nonbinding letter of intent, so that when other vendors call, they can say they have already committed and the decision has been made. |

P.m. |

The proposal had to be issued prior to the decision's being made. |

In our experience, time does not improve the likelihood of winning verbal commitments or getting proposals accepted. Once either is more than 30 days old, managers have cause for concern. When evaluating pipelines, we often see proposals out there for more than 60 days that are still assigned probabilities of 80-plus percent. Every month that a proposal doesn't close means that the chances of ultimately getting the order are decreasing.

In our experience, once a proposal is 45 days old, either it is heading toward no decision or the buyer has made a decision to go with another vendor and has elected not to give the seller the bad news. Even if you have had access to decision makers up to this point, after the proposal is in their hands, they usually don't want to talk with you. Either they haven't made a decision or they've made an unfavorable decision.

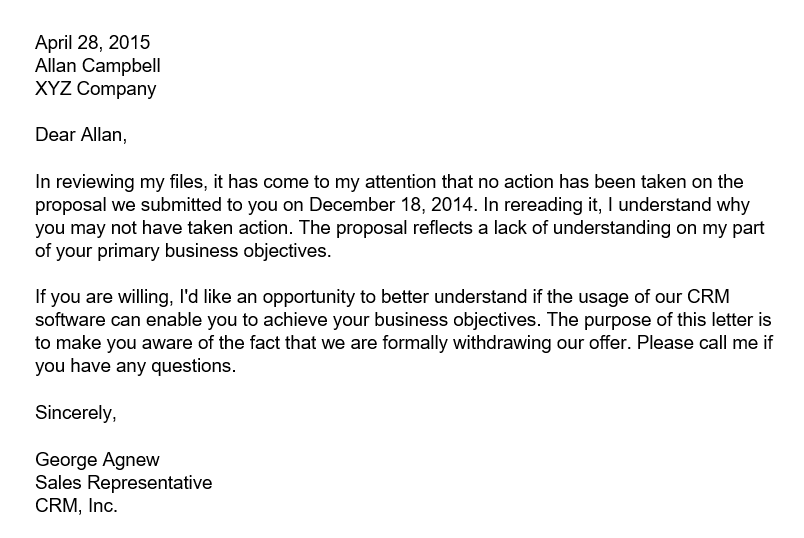

In other words, you relinquish a great deal of control once your proposal is delivered. Suddenly, the buyer has everything he or she needs, and access gets more difficult. Rather than wait and hope, consider taking some positive action if the proposal is out longer than you think is healthy for your chances of winning (30 to 45 days?). We suggest a take-back letter or a phone call withdrawing the proposal. If you opt for a letter, don't overnight it. The proposal has been out for over a month, and there is no sense in spending $11.95 to get the letter delivered the next day. Registered mail will have the same impact and will cost significantly less. Figure 16-4 is a sample letter.

Figure 16-4: Sample Letter for Withdrawing a Proposal

While some salespeople are terrified at the thought of withdrawing a proposal, the two most likely results are:

The buyer does not call back. At this stage, it is time to officially remove the opportunity from your forecast. Ultimately, it is better to get rid of deadwood in your funnel and pipeline, have a realistic view of what the next few months look like, and arrive at an appropriate business development plan.

The buyer calls you back and asks why you have withdrawn the proposal. This is an opportunity to determine whether the buyer is not going to buy, wants to buy, or would be interested in making changes to the proposal and trying to see if a favorable decision can be reached. If given a second chance, the seller now can focus on helping the buyer understand how to use your offering to achieve goals or solve problems.

A client mentioned that he had five quotes outstanding for over 60 days. Each was for $50,000 to $100,000. We suggested that he call each of the accounts and tell them he was withdrawing the proposals. Although he was skeptical of the wisdom of this move, he went ahead and did so. Within a few days three of the opportunities had closed. In two of the cases, the buyer indicated sheepishly that they just hadn't gotten around to issuing the purchase order.

Tomorrow Is the First Day of the Rest of Your Sales Career

We encourage salespeople and managers to be honest with themselves, and to assess and regrade every opportunity in their funnels and pipelines. When salespeople grade their opportunities against the new milestones, many discover that silver medal opportunities get purged from their forecast - and fast.

Clients will engage us to participate in these kinds of regrading sessions. These are usually done via conference call between the first-level manager, the salesperson, and the Customer Focused Sales consultant. A 45-minute session for each salesperson is scheduled for the first 3 months after the workshop. During each call with the salesperson, the top three opportunities are reviewed. In the first month, the Customer Focused Sales consultant does most of the talking. (Especially during the first month, it is far easier for a Customer Focused Sales consultant to disqualify opportunities, because he or she doesn't have any vested interest.) The second session is more of a sharing between our consultant and the sales manager. The client sales manager conducts the third session, with our consultant serving mainly as a safety net.

Most often, the overall value of the pipeline is reduced by 50 to 80 percent. That doesn't mean that 20 to 50 percent of opportunities are removed outright. Instead, it becomes clear that the opportunities are at either A or G levels. When we look at the value of the pipeline, we only look at E opportunities, which have been qualified to the point of having some visibility as to the potential close date. The mission of the seller is to get as many opportunities as possible to a level where the manager can grade them either a C or - ideally - an E. When existing opportunities are qualified to E status, some of the selling activities have already been done. The Sequence of Events is shorter, as the remaining activities amount to filling in the gaps, in contrast to starting with a new prospect.

To summarize: In assessing and developing salespeople, we advocate defining and sticking to a process. The Customer Focused Sales process introduced in this resource is an effective approach. It begins with the consistent positioning of offerings (through the use of Solution Formulators), and continues all the way through the development of salespeople - which, in the case of the salesperson, is the sales manager's job. Many of the same techniques that make a pipeline visible and predictable also contribute to improving the performance of the sales force - but only if the sales manager understands and accepts that responsibility.