Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 4: Discover the Ideal Customer

Overview

Optimum Engagement Strategies

In the Discover phase of the Diagnostic Business Development process, we establish a profile of the ideal customer for our offerings, match that profile to customers on an individualized basis, and craft a customized engagement strategy for initial contact. Its goal is to identify those customers who are most likely to be experiencing the issues our offerings address and the absence of the value we provide and, therefore, who have the highest probability of buying our products and services. The Discover phase encompasses all of the preparation activity before the actual diagnosis.

Discover is an especially critical element in enterprise sales. As the complexity and uniqueness of customers increase, so, too, does the need for and return on preparation. The greater our ability to customize and personalize our engagement strategies for individual customers, the greater our chances are of successfully gaining entry to their organizations and the more likely they are to feel that offerings have been designed specifically for them and that we are speaking directly to their world and their responsibilities.

Unfortunately, in their zeal to get face to face with customers, too many salespeople put far too little time and effort into this work. The percentage of salespeople who continue to "wing it" as they approach high-level executives is appalling. The typical attitude toward preparation all too often runs along these lines: If it walks like a duck and it quacks like a duck, a good salesperson should be able to sell anything made for ducks or, for that matter, anything made for birds. Therefore, the attitude, "Why prepare?" The problem in enterprise selling is that this one-size-fits-all attitude toward customers has worn out its welcome; it just won't fly. Nor should it.

Customers resist being treated as generic candidates for good reasons. First, they realize that they are simply impersonal targets in the eyes of the salesperson. They rightly suspect that they will be subjected to a one-sided view of the world and, perhaps, high pressure and other sales manipulations. Further, because their unique characteristics, situations, and problems have been largely ignored in the past, there is little basis for believing that the products and services being offered will create the optimal value for them. They believe that the time they spend with the salesperson may ultimately bring little, if any, return.

Just as significant is the fact that salespeople should also be avoiding the generic treatment of customers. The commonly accepted idea is that to maximize their performance, salespeople must maximize the number of prospects they see and the number of proposals they present. Thus, the less time they spend in preparation equates to more prospects and, somehow, increased sales, but it clearly doesn't work that way. Spending time with customers you aren't prepared for and who are unlikely to buy is inefficient and ineffective.

If you want to maximize sales results, you cannot simply allocate your time equally among all potential customers in your market. Instead, you must concentrate on the customer who has the highest probability of being negatively impacted by the absence of your solution and, therefore, the corresponding high probability of being receptive to your solution. The identification of that customer and the preparation to engage that customer is the purpose of Discover. If you rush through it unprepared, you end up gambling your time and efforts on an unknown prospect and, as a result, substantially lower your ability to predict your chances of success in the enterprise sale.

We keep the idea of the quintessential customer in the front of our minds by continually asking ourselves a simple, but fundamentally radical, question: Is there someplace better I could be? Successful salespeople understand that the best place to be is the place where they can leverage their efforts and maximize their overall performance as well as their customer's. They are continually moving toward that optimal engagement. As elements of success decrease with a current customer, at a certain point, the odds of success become greater with a new customer. There is someplace better we can be, and we need to take ourselves and our resources elsewhere.

How do sales professionals identify the best opportunities? Through a more comprehensive and creative approach to the Discover process, an approach designed to help salespeople:

Develop a clear understanding of the market for their offerings.

Identify and understand their potential customers.

Design the most effective engagement strategy for an individual customer.

Conduct the initial contact in a way that encourages the customer to invite them in and provide access to information and people.

Establish a diagnostic agreement that sets the stage for the next phase of the sale process.

Goals of the Discover phase can be divided into two groups: those that salespeople undertake to prepare for the initial engagement and execution of the engagement itself. We now take a closer look at these goals, how they are achieved, and how they add up to successfully complete the work of Discover.

Understanding Your Value

Every salesperson should consider this ancient proverb before embarking on the enterprise sale: "Know thyself." [1] It means that before we start trying to understand our customers' worlds, we should develop a full understanding of our own world and have a guiding vision that begins to define the ideal customer. More specifically, we need to understand our offerings, the markets they target, and the quantitative and qualitative levels of activity we must attain to reach our personal performance goals.

Self-knowledge begins with the value proposition inherent in the goods and services we are offering customers. In the context of enterprise sales, when we discuss value propositions, we are talking about the positive business and personal impact that your offerings deliver to your customers. This value represents your competitive advantage in the marketplace. It also forms a baseline from which you can begin to measure the fit between your offerings and prospective customers. The unique characteristics of your offerings help you define the ideal customer. If you are selling a logistics software package that allows the user to manage and coordinate tens of thousands of small packages with different destinations, the best place to spend your time is not with a company whose shipping patterns indicate that it transports full containers to only a limited number of destinations. Obviously, this customer will not be able to receive the value available in your solutions.

The analysis of the value proposition yields valuable conclusions about the characteristics of the most qualified customers for our offerings. For instance, if our company is a leader in innovative solutions, we should be looking for the early adopters in our target markets. If we are the high-value supplier in our industry, we should be looking for the customers who are the high-value suppliers in their respective markets. Value propositions tell us what segment of the industry is most likely to buy, what size company we should contact, and who we should seek out inside those companies. This information allows us to begin constructing an external and internal profile of what our ideal customer looks like.

This is common sense, but it is surprising how often we have found companies changing their value propositions without integrating those changes into the way the sales-force operates, how often changes in the selling environment render an existing value proposition ineffective, and/or how often we find salespeople who simply don't understand the value proposition they are offering.

Once you understand the value proposition you are offering customers, you can create a personal business development plan. An effective personal business plan must be linked to overall corporate strategy and operational objectives. We are all members of corporate teams, and our goals must be contributory to those of the larger organizational goals.

A personal business plan must have both quantitative and qualitative components. Most salespeople are already familiar with the quantitative aspect of a business plan. It is the common approach that tells us that if we contact a predetermined number of prospective customers, we will set a fixed number of appointments, that x number of appointments results in y number of presentations, and that y number of presentations yields z number of sales. The problem is that most plans stop right there, and salespeople end up struggling to achieve their quotas by crunching through vast numbers of prospects, working harder - not smarter.

Sales-by-numbers advocates do make sales, but they never excel at the enterprise sale and certainly are not making the best use of their resources. What they are missing is the qualitative element of the personal business plan. Qualitative metrics, which we have already derived from the value proposition, add an important dimension to a personal business plan. They allow us to begin to optimize our efforts and resources. For example, instead of simply telling us that we must call on 12 companies, a qualitative measure might take into account the fact that our value proposition is most attractive to companies with revenues between $15 million and $50 million and is more heavily weighted toward the top end of that range. Accordingly, our plan might stipulate that one-third of the companies we call on have annual revenues between $15 million and $30 million, that two-thirds have revenues between $31 million and $50 million, and that we do not call on companies whose revenues are above or below those figures.

The final component in understanding our own world is the opportunity management system that enables us to organize and schedule the activities of the personal business plan and the ensuing interaction with customers. There is only the most superficial need for opportunity management in conventional sales - the traditional salesperson chooses a prospective customer and drives that customer as far through the selling process as possible. Then, the salesperson moves on to the next opportunity.

In our sales process methodology, opportunity management is a more fluid process. Every customer is treated with a determined level of priority. Some prospective customers do not fit your qualification criteria at the time you first look at them; therefore, they may be monitored only at regular intervals to see if their fundamental indicators have changed. Others show a strong initial fit and are scheduled for further research.

Opportunity management encompasses how we develop and manage our leads. It includes early warning systems that tell us when specific customers are optimal for contact. For instance, a salesperson providing office storage systems might track commercial building permits and commercial real estate to identify sales leads. A building permit equates to a new building, which equates to new storage requirements.

As the opportunity represented by each customer changes, so does their priority in the salesperson's schedule. The ultimate purpose of opportunity management is to point salespeople toward that single individual or company that represents the best place they could be at any particular moment.

[1]According to the 16th edition of Bartlett's Familiar Quotations (Boston: Little, Brown), the admonition to "know thyself" dates from between 650 - 550 B.C. It was inscribed at the Oracle of Delphi Shrine in Greece.

Pinpointing the Quintessential Customer

Once we understand what an ideal customer should look like, the work of the Discover stage shifts to the individual customer. Successful salespeople take the time to prepare for the initial conversation with potential customers. They construct external and internal profiles of the customer's organization and ensure that those profiles match the profile of the ideal customer. They identify the driving forces and perspectives at work in the customer's organization and become familiar with the customer's goals.

By completing this work, sales professionals lay the groundwork for a successful initial conversation. They create a basis for engagement that enables them to speak with customers using the customer's language, frame the initial conversation around issues of importance to their customers, and build a perception of professionalism in the customers' minds that clearly differentiates them from their competition.

An external customer portrait tells us what customers look like from the outside, their demographics. It includes information such as the physical details of the company (size, revenues), industry and market position, and key characteristics that differentiate it from its competitors. An internal profile has two dimensions: how companies and the individuals within them think - which we call their psychographics - and what they are experiencing, their current situation. What are the indicators and symptoms that would manifest in the absence of the value you can provide? Psychographics includes information about how its leaders and employees approach and perceive their world - the organization's strategies, its driving forces and goals, and the attitudes and beliefs that underpin the behavior and decision making of management. The situational profile points out the physical conditions that, when present, will likely drive a decision to change.

In the enterprise sale, we are dealing with organizations where access is constantly sought and is tightly controlled. It is difficult to reach into the cast of characters; if we do engage, there is precious little time to differentiate and establish our value. Developing a full understanding of the customer before we make formal contact maximizes our chances of achieving a constructive engagement and developing the level of access required to accomplish our goals.

There are myriad resources that a salesperson can tap into for the previous information. The customer's annual reports, Web sites, publications of all sorts, and existing vendors of noncompetitive products; the salesperson's industry contacts and current customers in the same industry; employees in the potential customer's organization ... the list goes on and on. More important, and less common than a recitation of sources for customer information, is the content and analysis of the data we collect.

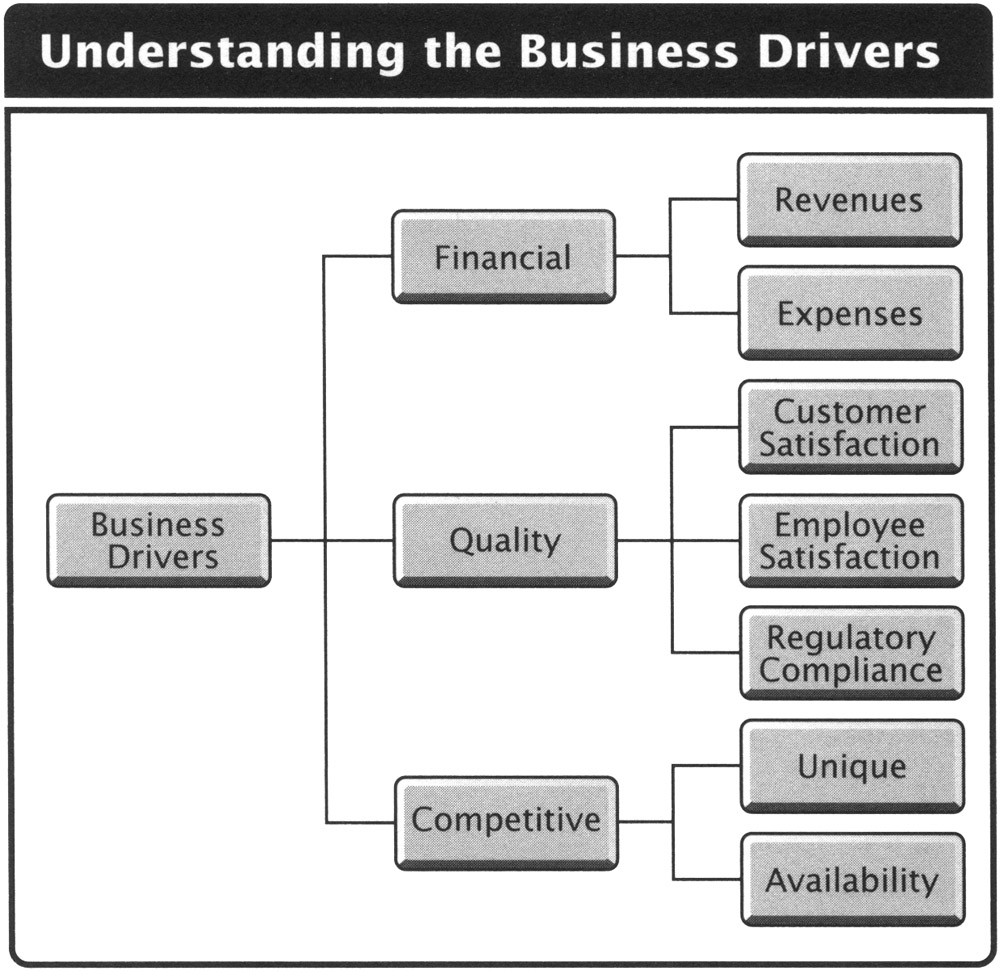

One effective way to analyze an organization is in terms of its business drivers, critical success factors or business objectives (see Figure 4.1). It is important to be able to categorize your offerings to effectively align your capabilities to your client's objectives. To simplify what could become an overwhelming list, we have determined that all business objectives can be placed neatly into one of three major categories:

Financial drivers are manifested by goals specifying either top-line growth via increased revenues or bottom-line growth via reduced expenses.

Quality drivers are manifested by goals based on increasing the satisfaction of the organization's customers, employees, or, for those in heavily regulated industries, regulators.

Competitive drivers are manifested by goals related to making offerings unique and assuring the availability of products or services to customers.

To identify long-term drivers, look to the customer's Web site for mission and vision statements. For short-term drivers, read the CEO's message in the annual report. It is a rare message that does not include concrete statements about the critical success factors driving the business currently and what will drive it in the near future. Confirm that the drivers identified in these sources are current (they can change fast) and then ask: To what degree are they at work in your prospective customer's business? How do they connect to your offerings?

What about the corporate culture at work in a customer's company? Personality and values trickle down from the top, so the smart profiler pays particular attention to the customer's executive committee members. What are their backgrounds? CEOs and other leaders who have risen to power have come out of different functions and, accordingly, have different perspectives. A CEO with a sales background may be focused on customer satisfaction; one with an engineering background may be more focused more on innovation. This information is often found in the public domain and is readily available.

The recent history of an organization also yields valuable clues to the atmosphere and personalities you can expect to encounter when you contact customers. Have there been restructuring, workforce reductions, mergers, and acquisitions? All of these events leave a mark on the organization and offer clues as to what objectives and emotions drive their decision-making criteria.

We close this discussion with an example of creative customer profiling at the Discover stage. A major player in the trucking industry was initiating a complete logistics management service. Its customer profile called for a manufacturer who was a forward-thinking innovator in other business processes. The team set its sights on earning the business of a major computer manufacturer. One way in which the sales team developed its understanding of the potential customer was to spend several days outside the company's manufacturing facilities. They counted the number of trucks inbound and outbound and the number of different trucking companies represented. The team talked to drivers at local truck stops to get a sense of the size of the loads, their origins, and final destinations. They used the raw data they collected to create a picture of the computer maker's logistics flow and calculate estimates of the related costs. When the sales team finally met with the computer manufacturer's management, the managers were astounded by the sales team's depth of knowledge about their operation and intrigued by the potential value that could be achieved through the company's logistics services. They elected to pursue the matter further and eventually transferred their logistics business to our client.

Expected credibility is what you know about your solution and your business. Exceptional credibility is what you know about your customer and their business.

The point here is not that we should start camping out at our customer's facilities. Instead, it is that the better developed our profile of a potential customer is before we initiate contact, the greater our ability to create a strong value assumption; there are endless means of acquiring intelligence before the initial engagement. This, in turn, enables us to craft a one-of-a-kind introduction, one that our customers will feel was prepared specifically for them and could not be used with anyone else. It allows us to quickly hone in on the customer's critical issues, establish ourselves as professionals, and differentiate ourselves from the competition. In short, it represents extreme relevancy. This creates a compelling platform for a very constructive engagement and immediate and complete access to the customer.

Diagnostic Positioning - Creating the Engagement Strategy

When the external and internal profiles we develop confirm our view of a prospective customer as a quintessential customer, it is time to create an engagement strategy for our initial contact. There are two elements in an engagement strategy: One is unchanging and comprises the framework on which we will always structure our encounters with customers; the second is ever-changing and is the identification of the best entry point into the customer's organization.

This may sound harsh, but it is nonetheless a reality that sales professionals must be prepared to face. The most effective way to break through a customer's preconceived notions about salespeople is to do something actors call "playing against type." When we act in unfamiliar ways, customers are jarred into seeing beyond the stereotypical character they have come to expect.

Breaking Type

There are several ways that successful salespeople play against type. We've already introduced the first in Chapter 3 - going for the no - the idea that as salespeople, we should always and actively be looking for reasons to end engagements with individuals we can't help. When we are willing to break off or suspend an engagement with a customer who is not experiencing a problem that our offering can solve, we play against the stereotype that says salespeople never take no for an answer.

An extension of the concept of going for the no and another way we can play against type is to always be leaving. How do most salespeople appear to the customer, relative to "staying" or "leaving?" That's right - they look like furniture - they're not likely to leave, like a pesky little pit bull clamped on your ankle. The more you try to shake it off, the tighter those little jaws clamp down. To be rid of the stereotypical salesperson, customers expect to have to hang up the phone mid-sentence or call in security. Salespeople who are unwilling to end engagements leave their customers feeling pressured and tense. But when we indicate our willingness to step back, customers feel free to communicate openly and without fear that the information they share will be used against them.

We can communicate these attitudes from the very beginning of our contact with customers. For example, on our first phone call with a potential customer, we can introduce ourselves and then, as a prelude to the subject of the call, say, "I'm not sure if it is appropriate that we should be talking. . ." That simple phrase relaxes the customer and indicates that the salesperson is not about to force his or her way forward. It tells the customer that the salesperson is willing to be somewhere else if that is more appropriate. It clearly sets the stage for a professional encounter.

One last way we can play against type is by being prepared not to be prepared. The stereotypical salesperson feels pressured to always have an answer. Part of the reason lies in human nature itself; no one likes to admit that they don't know the answer to a question. The other part is that a conventional salesperson sees a customer's question as a golden opportunity to start presenting. Superior salespeople, however, break type. Because they are completely prepared, they can afford to be relaxed and casual. They don't need to force an answer before they fully understand the customer's situation and, as important, they understand that even when they do have an answer, if the customer is not prepared to hear it or won't fully understand it, it might not be the right time to offer it.

For instance, customers often ask salespeople, "What makes your product better than your competitor's?" The natural response is to launch into a dissertation about the unique benefits of your offering, and when you do, you are fulfilling the image of the conventional salesperson. The counterintuitive response is to step back from the challenge and say, "I'm not sure that it is. Our competitor makes a fine product and at this point, I don't understand enough about your situation to recommend which product may be a better fit for your application. Let me ask you this . . ." and then goes on to ask the next diagnostic question. The salesperson who responds in this manner opens the door to a more in-depth discussion and greater involvement. The key to the engagement strategy is the diagnostic positioning - we are positioned to Diagnose, not present.

Identifying the Optimum Point of Entry

The final element of the precontact phase of Discover is the identification of the best point of entry into the customer's organization. In conventional sales, the point of entry is usually fixed by the job title of the contact and frequently targets "the buyer." Sellers of training programs call on training managers and human resources executives, sellers of software call on information technology managers, sellers of manufacturing equipment call on plant managers, and so on. All are in search of the sole decision maker, a mythical character who, for all practical purposes, does not exist in the enterprise sale.

The problem with this fixation on job titles is twofold. First, every salesperson in your industry is calling on the same person inside the customer's organization, so that person has had significant practice at putting up barriers and restricting access. Even when contact is made, salespeople's ability to establish themselves as unique is severely impacted. Because of the frequency with which the "usual suspects" must deal with salespeople, they are usually immune to even the best moves. Second, the usual suspects are often not the best initial contact. It isn't unusual to find a major disconnect between the individuals who are experiencing the impact of the problem and those who are tasked to buy the solution. Typically, we find that it is middle managers who are busy avoiding buying decisions while unidentified individuals at the executive and operational levels of the organization are experiencing the consequences of the problem and the impact of the absence of the salesperson's solutions.

Successful sales professionals, on the other hand, tend to enter customer organizations through less obvious and more productive avenues of access. They identify the best entry points by determining who in the customer's organization is experiencing the impact of the absence of what they can provide. That, most likely, is an individual whose ability to accomplish personal and professional goals is being restricted by the problem or lack of solution. For instance, one of our clients provides automated manufacturing systems that place components on printed circuit boards. Manufacturing or production engineers typically purchase these machines and the manufacturing lines they are in; therefore, every salesperson initiates contact there. As we worked with this client to develop an optimal entry strategy, it was determined that the early warning indicator is their prospective customer's losing bids or turning down bids because of lack of ability to place certain size components. The victim in this example, or the person most acutely aware if this is occurring, is the salesperson who is turning away the business. A call to a customer's salesperson was very simple. The equipment salesperson explained the nature of the call, "I'm trying to determine if your organization is experiencing this issue, and if so, would it make any sense to discuss it further with your management?" The diagnostic questions determined that this company was in fact turning away business, which quickly led to a calculation of the financial impact; a suggestion was made to talk with the regional manager. (Is this an isolated case, or is it happening to other salespeople in other territories?) It was determined that the salesforce had been forced to turn down $8 million of new business because current equipment could not handle a certain component that our client's equipment was capable of placing on circuit boards. With the cost of the problem in hand, the regional sales executive brought the salesperson to the vice president of sales, who took him to the vice president of operations, who in turn called in the manufacturing engineers and told them to make the sale happen.

The individuals in the business who are adversely affected by a business problem or inefficiency are much more receptive to discussing it, and the impact, than the individuals who may be the cause of the problem.

In this example, a manufacturing engineer, who is more isolated from the company's customers, sees little value in the new capability of the salesperson's equipment, but the sales executive knows that customers would buy if they could build the boards with the special component. Likewise, a processing plant manager who already has a set amount of downtime built into this year's budget may have little interest in spending unbudgeted funds for automated control equipment that promises to reduce the downtime next year. Executives at the corporate level, who would see the increased production capacity in future years drop straight to the organization's bottom line, would be operating from a completely different perspective. Again, the optimum entry point may likely be the nontraditional choice.

Superior salespeople seek to enter the organization through the door of the person who is experiencing the symptoms of the problem in a way that would be most likely to drive a decision to change. When they identify the person "who gets the call in the middle of the night," they've found the person who cares most about the problems their offerings address.

Answering the Customer's Questions

Once you have identified the person who represents the best point of entry to a potential customer, it is time to initiate the first formal contact. Many books have been written about this initial contact. They cover telephone skills and conversational gambits aimed at one thing - getting the appointment. Unfortunately, most miss the most important consideration in the initial customer contact.

Successful salespeople think beyond simply setting the appointment. Their goal in the initial conversation is to determine if this customer is the optimal place to invest their resources at this time. The more resources they involve in the initial appointment, the more scrutiny they give this conversation. They want to get invited into the right customer's organization by the right people for the right reasons. The real secret to "getting invited in" is in approaching your first conversation from the customer's perspective and by focusing the content of your call exclusively on the customer's situation. Successful salespeople don't initiate contact by talking at length about their companies, their offerings, or themselves. They introduce and describe themselves through the issues that they address, not through the solutions they offer, diagnostic positioning.

Any time a prospective customer picks up the telephone and speaks to a salesperson for the first time, the customer is seeking answers to a short sequence of questions. The key to being invited in is in offering customers the information they need to answer each question - no more and no less. If the customer is able to answer questions in a positive way, the result is continued interaction. If not, the conversation is over. The questions that customers ask themselves are simple, and the answers they infer are considered from only one point of view - their own:

Should I talk with this person?

Is this call relevant to my situation?

Is this something we should discuss further?

To talk or not to talk? That is the question and the starting point of all conversations. It's a basic decision, and its answer is determined on basic information. You know what makes you decide not to talk - the mispronounced name, the rapid-fire delivery, or the canned spiel. Consider the things that make customers decide to stay on the line with a salesperson. Certainly, the sound of the salesperson's voice is one. Does this person have a professional tone - relaxed, not rushed? And, what about the introductory statements callers use? Does the caller say the customer's name? Has the caller been referred by someone the customer knows? Is the caller talking to the customer or reading from a page? Does the caller suggest that the conversation that is about to ensue may not be appropriate? (Suggesting to customers that the call may be inappropriate is an empowering statement. It immediately relaxes the customer and actually begins the conversation with agreement. It also suggests that the salesperson will not pressure them if they feel that there is no value in the conversation.)

All of this adds up to a single judgment in the customer's mind: Does this caller sound and act like a professional, like a colleague? When we sound professional, customers stay on the line. When we don't, they don't.

The next question customers consider is whether the call is relevant to their current situation. Customers want to know if we understand their world, and we need to prove that we do. Here, successful salespeople begin to demonstrate the knowledge they have obtained about the customer's industry and company. If you were in the customer's shoes, you would want to know if the caller typically works with (as opposed to sells to) people like you. What kinds of issues do the salesperson's solutions typically align with? Do these issues concern the customer? Once this information is communicated, the customer is ready to make the final decision in the initial contact.

The final question customers consider is whether the initial contact should be extended. They are trying to figure out if this salesperson can add to their understanding of the problem at hand. The customer often asks questions such as, "How can you help me?" Conventional salespeople are very happy to begin presenting solution ideas now, but top-tier salespeople take a step back and begin to describe the diagnostic process through which they will guide the customer. At this point, they begin to establish the ground rules for further engagement.

Establishing a Diagnostic Agreement

The final task of the Discover phase is the establishment of a diagnostic agreement. Diagnostic agreements are informal, verbal agreements between the sales professional and the customer that lay out the ground rules for a constructive engagement. The agreement prepares for the beginning of the Diagnose phase of the sale process. A diagnostic agreement sets a professional tone for the continued conversations between the salesperson and the customer and sets the stage for open, unfettered communication. This is accomplished by setting limits on future conversations, thus assuring customers that they will not be forced into situations in which they are not comfortable.

The effective diagnostic agreement explicitly defines parameters for continued conversations, a proposed agenda, the participants, and feedback plans. It sets up the flow and specifies individuals who should be involved and topics to be covered. It also specifies mutual "homework" - what facts and figures we need to check for symptoms of the customer's problem, what information and resources the customer will bring to the meeting, and what information and resources the salesperson will bring. This is unique in the sales world where getting in the door is usually considered the ultimate goal of the first contact, but it is a standard feature in other professions such as law, medicine, and consulting. When we assign homework, we cause customers to begin to think about their situations, the specific symptoms of their problems, and the impact they have. We involve them ahead of the engagement, and we signal our intent to discuss their situation in more detail.

After the salesperson and the customer create a diagnostic agreement, the Discover phase is complete. The salesperson knows that he or she is spending time in the best place, and customers know that they are dealing with a professional who can be trusted and will treat them ethically and with respect.

Discovery is a term used by lawyers to describe the process of gathering information on which they will build their arguments. Because we've borrowed that term from the legal profession, it is only fair to let a lawyer have the last word about this phase of the sale process. Gerry Spence, who regularly appears on news programs as a legal analyst and is the "winningest trial lawyer in America," devotes a full chapter in his book, How to Argue and Win Every Time, to the importance of case preparation. He pegs his success to the fact that he spends more time than his opponents to prepare to enter the courtroom. Spence, who has never lost a criminal case, declares: "Prepare. Prepare. Prepare. And win." [2]

[2]See Gerry Spence's How to Argue and Win Every Time (St. Martin's Press), p. 134 for excellent practical advice on effective communication.