Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 5: Diagnose the Multidimensional Problem

Overview

The Optimal Source of Differentiation

The core competency of the enterprise sale is the sales professional's ability to perform as an expert diagnostician. This diagnostic expertise enables us to help customers analyze and understand the causes and consequences of their problems, a critical prerequisite of a high-quality decision. Equally important, it allows us to shift the emphasis of our engagement with customers from our solutions to their situations, a shift that differentiates us from our competitors, creates significant learning for the customer, and builds the levels of trust and credibility through which our customers perceive us.

These outcomes stand in stark contrast to the conventional sales process, which depends on customers to understand and communicate their problems to salespeople. Popular and rarely questioned selling strategies such as consultative selling, needs-based selling, solution selling, and even value-added selling all depend to a large degree on the customer's ability to self-diagnose and self-prescribe, an expertise that we have already shown is in short supply. Largely, customers are not experienced in diagnosing multidimensional problems, designing enterprise solutions, and implementing enterprise solutions.

The assumption that customers can and should be diagnosing themselves causes further damage when salespeople, thinking that their customers understand their problems and the need to resolve them, prematurely focus on solutions. Describing solutions without establishing a compelling need for them creates intellectual interest and curiosity among customers instead of the emotional discomfort needed to drive change. As a result, the conventional salesperson wastes time and effort on the intellectually curious customer, while the economically serious customer, who is actually experiencing the indications and/or consequences of the absence of the solution, stands by unrecognized and unattended.

When we salespeople are in the diagnostic mode, we are dealing directly with our customers' reality. That is, we are working with problems that they have experienced in the past, are currently experiencing, or to which they believe they will be exposed in the future. In fact, our customers may not be aware that they have these problems and might be missing a significant opportunity. As we discussed in Chapter 3, when customers realize that they are dealing with real problems and real costs (as opposed to future benefits), the urgency that drives the decision to change is created. They find themselves on the critical, actionable end of the change progression. Diagnosis, as it methodically uncovers real problems and expands the customer's awareness, causes the customer to move along the change progression.

Our ability to diagnose customer problems sets us apart from the competition. Most salespeople devote themselves to establishing expected credibility. They lean on the presentation of their company's brands, history, and reputation. The irony of this approach is that it makes them sound like everyone else (and reinforces the trend toward commoditization). This conclusion is validated repeatedly when we ask business associates how much their "credibility story" differs from their top competitors' stories. Only a few are willing to stand and declare that there are significant differences. The ability and willingness to diagnose will provide a significant difference between our competitors and us. It gives us the opportunity to establish exceptional credibility in our customers' eyes.

The quest for exceptional credibility in the Diagnose phase of the sale process has two primary goals. The first is to uncover the reality of the customer's problem. The professional salesperson cannot and will not recommend a solution without first confirming that the customer is actually experiencing the problems it is meant to solve or is poised to capitalize on the opportunity the solution represents.

The second, and more important goal of the Diagnose phase, is to make sure that the customer fully and accurately perceives all the ramifications of the problem, the absence of the solution. The decision to buy is the customer's decision, and the only way to ensure the quality of that decision is to ensure that the customer fully understands the problem and the consequences of staying the same. This is analogous to the job of the psychiatrist. An experienced psychiatrist may be able to diagnose a patient's mental illness after a single visit. After all, the doctor has treated many other patients who suffer from the same disease. Yet, it may take several sessions before the patient believes he or she has a problem and believes that the doctor also understands that problem. Psychiatrists know that until patients come to those realizations, they will have no credibility in patients' eyes, and the path to a cure will remain blocked.

When salespeople fail to reach either goal of the Diagnose phase, their ability to win enterprise sales is severely compromised. The outcome of the sale becomes as random and unpredictable as the results of the conventional selling process. When we don't diagnose an intricate problem, we have no basis for designing and delivering a high-quality solution. If we diagnose complicated problems, but don't help our customers to fully comprehend them, they will not see the need for change and will not buy. Successful sales professionals strive to recognize and achieve both goals of a comprehensive diagnosis for all of these reasons.

The raw information that we need to make an accurate diagnosis comes primarily from the customer; thus, the quality of the sales professional's questions becomes the primary skill of the information-gathering process. The value of asking questions is also predicated on another important skill, listening. Noted doctor and author Oliver Sacks states: "There is one cardinal rule: One must always listen to the patient." [1] Questions are more than tools to elicit information, however. When questions are being asked and answered, the customer is forming opinions that will be critical to the outcome of the decision.

Conventional salespeople tell stories about their solutions. Prospective customers expect to hear these stories and rarely take them seriously. What is taken seriously is the concern and expertise we display in the questions we ask customers. The right questions form the basis for customer opinions concerning how well salespeople understand customers' problems, whether they can help customers expand their own knowledge of the problems, and how likely they are to be the best source for the solution.

Superior salespeople are guiding their customers to four elemental decisions in the Diagnose phase; they are deciding:

That a problem does indeed exist.

That they want to participate in a thorough analysis of the problem.

That the problem has a quantifiable cost in their organization.

Whether that cost dictates they must proceed in the search for a solution.

When we help our customers successfully complete these decisions, it is highly likely that we have earned exceptional credibility in their eyes and have stepped into the customer's world as a full-fledged business partner "and a source of business advantage." We next take a closer look at how superior sales professionals help customers make these decisions.

[1]Dr. Sacks' quote appeared in Forbes, (August 21, 2000), p. 304.

Establishing the Critical Perspective

In the enterprise sale, we work with multiple individuals in the customer's organization to develop a comprehensive view of the situation. Each of these individuals has some of the information we need to diagnose the problem, and each has a unique perspective. It is a lot like the often-told story of the blind men and the elephant. Each man approached the elephant at a different point and, as a result, each described the animal in a radically different way.

To communicate most effectively with each of the individuals who has information about an intricate problem, to obtain the best information they have to offer, and to evaluate the validity of that information, we first must consider the critical perspective of that person. We need to understand the mind-set and position from which they are seeing the symptoms of the problem.

We ask three questions designed to help us understand a person's critical perspective:

What is this person's education and career background? In Chapter 4, we talked about how the background of an organization's leaders can affect the way the entire organization thinks. So, too, the background of an individual colors his or her personal perspective of the world. A person with an education in accounting approaches and perceives a problem differently than a person educated in marketing. Further, uncovering the professional and educational disciplines that influence a person's thinking can be particularly helpful when you are working with senior management, where a person's background is often not directly related to his or her current job.

What are this person's job responsibilities? An individual's critical perspective is going to be intimately linked with his or her current goals and duties. Certainly, personal concerns about job security and performance are among the most powerful forces at work on the change spectrum. Salespeople should always remember that it is easier for them to find a new customer than it is for their customers to find new jobs.

What are the work issues and problems that concern this person? We often find salespeople trying to engage customers in issues and problems that exist outside an individual's area of responsibility or that may not exist at all in the customer's critical perspective. For instance, a director of quality who is charged with maintaining unit defects at a consistent Six Sigma level perceives an innovative new solution for speeding the manufacturing process from a different perspective than does a plant manager who is charged with obtaining higher output. The former is perfectly happy with the status quo (if it has reached Six Sigma) and highly resistant to any change that could threaten it, while the latter sees the status quo as a performance problem that must be addressed.

Salespeople will begin to understand customers' worry lists - their individual job concerns and issues - by asking themselves about the typical concerns of individuals with this particular job title. The director of quality is concerned with issues such as product defects, process reliability, and customer satisfaction. As soon as we get face-to-face with this person, we must confirm the existence of those concerns and narrow our focus on specific areas of dissatisfaction.

The conventional approach to selling depends on laundry lists of questions that focus on needs and solutions. The disadvantage of this process is that the salesperson may not connect with concerns until a dozen or more questions have been asked, long after the customer's patience has worn thin. In our diagnostic approach, we use an A-to-Z question, which is designed to instantly bring to the surface the customer's most serious concern.

As you read the question, think about the answer you would give. We would ask: "As you consider your sales process ... beginning with generating a new lead ... moving on through all the interactions with a customer ... and finally, ending up with a profitable new customer ... if you had to choose one part of the entire sales process that concerns you the most ... as well as things are going for you ... what concern would you put at the top of your list?"

Before we discuss your answer, look at the question again. This is a long question, and the way it is asked, with plenty of pauses with a long thoughtful look or two at the ceiling, makes it even longer. There is good reason for that. We are pacing the customer's thinking process, giving him time to create a thoughtful response. It is designed to frame the customer's thinking within a certain process in his job responsibility. Another important element of the A-to-Z question is that it sounds spontaneous, not like the typical canned question. It is designed to elicit thoughtful consideration and a meaningful response from the customer.

There is one more element to address - the phrase "as well as things are going for you." This defuses any defensiveness the customer is feeling. Without a phrase like this, a likely response could be: "Things are going quite well, thank you." By acknowledging and complimenting customers' past successes, you are suggesting that with their success, they are perhaps interested in getting even better. The phrase eliminates the customer's need to defend or proclaim past success.

Returning to the previous question, did you think about the question; did it trigger a review of your sales process? Did you believe the question was sincere and try to address it seriously? Most people do. In fact, when we ask A-to-Z questions, we stop and listen. Silence is good. The longer the silence lasts, the better the answer is. The A-to-Z question is a most effective means of getting to the heart of the issue.

Peeling the Onion

In a perfect world, salespeople and customers communicate openly, honestly, and with complete clarity about the problems the customer is experiencing. But we don't work in a perfect world. In the real world of enterprise sales, customers are often unaware of the full extent of their problems; even when they do understand them, they are just as often reluctant to share that information. Salespeople don't usually ask what they really want to know first, and customers don't usually say what they really mean first. This lack of openness, which we all exhibit to one degree or another, is a natural and common protective behavior that has evolved from childhood.

When we communicate through the critical perspective of our customers, we begin to overcome the barriers to communication. Empathy, however, is not enough. Our customers need to be assured that it is safe to share information with us and that we will not use the information they provide to manipulate them. We communicate that assurance by our willingness to walk away from an engagement whenever the facts dictate that there is no fit between the customer's situation and our offerings. This is no sacrifice on the salesperson's part. When we spend time with a customer who has no problem, we simply waste our most valuable resource - our time.

The second way we assure our customers that we can be trusted is to approach a diagnosis at the customer's pace. Leading a witness is forbidden in a courtroom and should also be forbidden in the enterprise sale. Customers must discover, understand the impact of, and take ownership of problems before deciding to seek a solution. Yet, customers rarely reach conclusions about their problems at the same time that salespeople do. When salespeople move too quickly and too far ahead of their customers, they create a gap that customers often see as applying pressure or manipulation. The result is mistrust and a confrontational atmosphere.

Crossing customers' emotional barriers to get to the heart of the issues that concern them is like peeling an onion. When we "peel the onion," we accomplish two goals. First, we pass through the layers of protection that customers use to shield themselves from the potentially negative impact of open communication. We move from cliché (which is the surface level of emotion) through levels of fact and opinion to the most powerful driver of change - true feelings.

People reveal their true feelings and problems only when they believe that their input will be respected and no negative consequences will result from the information they share. Successful salespeople are careful to communicate by word and deed that they mean customers no harm. This nurturing attitude enables open communication and mutual understanding and maximizes the probability of a quality decision.

We peel the onion using a series of deliberately structured questions, which we call a diagnostic map. Too often, salespeople ask questions simply to prolong conversations until they can create openings to present their solutions. The result is surface communication and superficial engagement. The diagnostic map, on the other hand, is designed to explore issues in an accurate and efficient way while creating the trust needed to elicit forthright answers from our customers.

One way we move through a diagnostic map is with the assumptive question. Assumptive questions are phrased in a way that assumes the customer is capable and knowledgeable. It is a good way to communicate respect and engender trust. This phrasing is very important.

When we worked with a company selling disaster recovery software, we found that its salespeople were using a slide presentation designed to educate their clients about the risks they were incurring without their software. One slide boldly stated: "Eighty percent of companies under $100 million in sales do not have disaster recovery systems." The salesperson would then ask, "Do you?" If you were the customer confronted with such a question, how would you react?

In contrast, we designed an assumptive question to address the same situation: "When you put together your disaster recovery plan, which of the potential bottlenecks gave you the most concern?" This implies that the customer knows his or her business, and because it assumes the best, the customer is complimented by that assumption and it makes the customer feel safe enough to admit that there is no plan in place. It has the added benefit of introducing the idea that the customer might be exposed to a serious, and thus far, unaddressed risk. The sequence of thoughts the customer goes through is (1) feeling complimented, (2) realizing they haven't considered the issue, and (3) recognizing the sales professional has added considerable value by introducing a topic that should not be overlooked, thus creating trust of the sales professional, concern for the issue, and credibility of the sales professional in preventing a flawed decision.

The second goal of peeling the onion is to establish the existence and extent of the problem itself. Again, questions play the starring role in this work. A second type of question, the indicator question, is used to identify the symptoms of the kinds of problems our offerings are designed to solve. An indicator is a physical signal. It is a recognizable event, occurrence, or situation that can be seen, heard, or perceived by the customer. It doesn't require an expert opinion, and we are not asking the customer to self-diagnose. Instead, we are simply asking for an observation.

The difference between opinion and observation is important; the easiest way to make it clear is to look to the medical profession. If a heart surgeon made a diagnosis as a conventional salesperson does, it might sound like this:

SURGEON: "So, how are you feeling today?" PATIENT: "Great. I feel good."

SURGEON: "Have you been thinking about doing anything with your heart?"

PATIENT: "Well, quite a few of my friends have been having heart surgery. So I thought maybe I should consider it, too!"

SURGEON: "Are you leaning toward angioplasty or bypass?"

It's a silly exchange, but notice that it is based on self-diagnosis. The doctor is asking the patient for an expert opinion, and that is exactly what the conventional salesperson does. In reality, doctors don't put much value in patients' opinions, but they do value patients' observations. They ask indicator questions, such as "Have you noticed any shortness of breath lately?" and "Have you experienced any dizziness or numbness?" These questions ask the patient for an observation and lead to additional questions and a more in-depth diagnosis.

At this point, the salespeople often ask what to do if no problem indicators are present in a customer's organization. The answer is simple: The engagement is over, or at least the diagnosis is postponed until such indicators appear. If there are no indicators, there is no problem. No problem means no pain; thus, the probability that the customer will make a decision to change is very low. It is time for the salesperson to move this customer into his or her opportunity management system and engage new customers who are experiencing the indicators of the problems he or she solves.

Another tool for tapping into the desire to be understood is a question called the conversation expander. Like indicator questions, these questions give our customers the opportunity to expand on explanations and clarify their thoughts. We can ask them at any stage of the sale process. Examples for use during problem analysis are shown in Figure 5.1.

Indicator Expansion

Could you expand a bit on ...?

Tell me more about ...

You mentioned a concern about ... Could you walk me through that?

Could you help me understand ...?

Example of Situation

What would be an example of ...?

Could you give me an example of. ...?

What would an example of ... look like in your business/industry?

I'm not clear how ... works. Can you give an example?

Duration

When did you first start to experience ...?

When did you first notice ...?

Has ... been happening for long?

How often does ... happen?

Figure 5.1: Conversational Expanders

When indicators are present, however, we continue the questioning process to expand our own - and the customer's - understanding of the problem. We continue peeling the onion and exposing the full dimensions of the problem by creating sequences of linked questions. We link questions by building each new question on the customer's answer to the previous question. When we do this, we are encouraging further explanation and additional detail. Communications experts tell us that humans have a natural desire to be understood. With each new question, we tap into that desire in our customers and together reach a deeper understanding and a greater level of clarity about the problem.

We ask diagnostic questions to establish a chain of causality. Indicators represent the symptoms of a problem, but symptoms represent only clues to actual causes of a problem. As any doctor will tell you, eliminating the symptoms of a problem does not solve the problem. For instance, a patient may use an antacid to ease the pain caused by an ulcer, but the antacid does not cure the ulcer nor does it address the causes of the ulcer. In fact, eliminating symptoms often masks the problem and even exacerbates them, enabling the problem to continue undetected.

We identify the causes of problems by asking questions about their indicators. When we determine the causes of a problem, we have also reached causes of the customer's dissatisfaction. That dissatisfaction is the vehicle that drives the decision to change, but simply establishing the existence of a problem is not a complete diagnosis.

Calculating the Cost of the Problem

Salespeople can do a thorough job of establishing and communicating the symptoms and causes of customers' problems, present viable solutions to those problems, and still walk away from the engagement empty-handed. This outcome most often occurs when salespeople ignore a crucial piece of the diagnostic process - connecting a dollar value to the consequences of the problem.

Problems run rampant in organizations. Some are not significant enough in consequences or risk to address; others must be addressed because their consequences or risks are too high. The fact that a problem exists is not enough to ensure change. When the customer does not know the actual cost of a problem, the success of winning the enterprise sale is severely compromised.

Typically, customers do not quantify the costs of complicated problems on their own. The main reason for this, as we saw in Chapter 2, is that most customers simply don't have the expertise required to fix those costs. Even when they do attempt to quantify their problems, they usually focus on the surface costs and tend to overlook the total cost.

When we define the cost of the problem, we put a price tag on the dissatisfaction the customer is experiencing. That tag enables customers to prioritize the problem and then make a rational, informed choice between continuing to incur its cost and investing in a solution. In fact, as we see in the next chapter, establishing an accurate cost of the problem is the only path to defining the true value of a solution. Cost is also the surest way to shorten the customer's decision cycle. Think of the customer's pain as the decision driver and the cost of the pain as its accelerator. The higher the cost of the problem, the faster the decision to solve it.

Salespeople also tend to shy away from fixing costs. Many complain that it is too hard to determine, but we find that the real reason is that they are afraid that the cost of the problem will be too low to be addressed and the engagement will be over. They are reluctant to do anything that might interfere with "going for the yes." This is always a possible outcome, and it is a legitimate one. If the cost of a customer's problem does not justify the solutions being offered, the professional will acknowledge that reality and (in the spirit of "always be leaving") move on to a better qualified customer. If this happens too often, the salesperson and his or her organization have a larger problem - solutions are too expensive in terms of the value they offer customers.

Another common objection to cost calculation that we hear from salespeople is that their offerings are not meant to solve problems. They say that they provide new opportunities; therefore, they can't fix the costs. This is not a.valid objection. There are no free moves in business. There are always costs present in every decision. Even when a solution offers a new capability, there is still a cost if the customer chooses not to adopt it.

All businesses measure their performance in dollars and cents. Therefore, any problem they are experiencing or opportunity they are missing can be expressed in financial terms. Until you quantify that impact, you are dealing with a highly speculative issue.

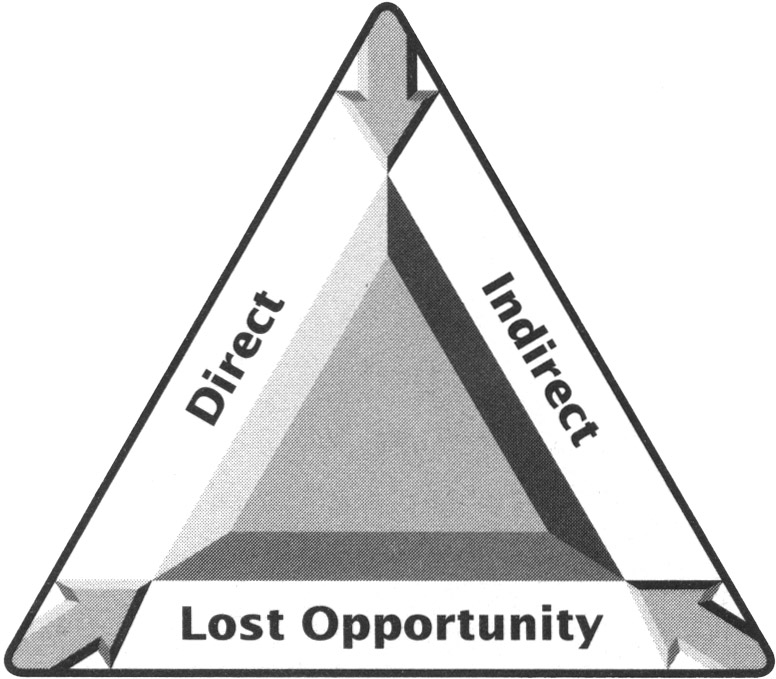

When salespeople explore the total cost of a problem, they need to use a combination of three types of figures:

Direct numbers: Established or known figures.

Indirect numbers: Inferred or estimated figures.

Lost opportunities: Figures representing the options that customers cannot pursue because of the resources consumed by the problem.

When we talk about the total cost of the problem, we are not saying that you must establish a precise figure. Rather, the cost must be generally accurate. Calculating costs is a process similar to the navigational method known as triangulation. By sighting off of three points - the direct numbers, indirect numbers, and lost opportunities - we can arrive at a cost that is accurate and, most importantly, believed by the customer (see Figure 5.2).

This is accomplished in two steps. First, we salespeople need to provide a formula that is conceptually sound. Second, we must ensure that the numbers plugged into that formula are derived from the customer's reality, not the salesperson's. We know we have successfully completed these steps when our customers are willing to defend the validity of the cost among their own colleagues.

The following example shows how a cost conversation works. A salesperson in the shoplifting detection equipment industry calls on independent pharmacies. He engages the owner of a drugstore with revenues of $3.0 million, who is experiencing the industry average shrinkage of 3 percent. This tells the salesperson that the store is losing $90,000 annually to some combination of customer theft, employee theft, and sloppy inventory management. The store manager, who does not believe that the store is experiencing any significant customer theft because the store is in a "better part of town," is not interested in the salesperson's offering.

The salesperson agrees with the customer's point (atmosphere of cooperation) and then asks an Indicator question, "Do you ever notice empty packages on the floor?" The store manager replies, "You have a point there, but it's not enough to be worried about." "Probably not," the salesperson replies and then asks the next question to establish an indirect number. "Out of every 100 people in this community, how many do you think would shoplift?" The curious manager replies, "One percent, 1 out of 100."

The salesperson now asks for a series of direct and indirect numbers, such as the number of buying customers in the store each day and the ratio of buying customers to browsers. They yield a figure of 533 people in the store each day. The salesperson asks, "What do you think the average cost of a shoplifting incident would be?" The manager replies, "$30."

From this information, the salesperson calculates that there are five shoplifters in the store each day, and the average daily loss is $150. Further, the store is open 365 days each year, making the annual loss $55,000 - a believable figure in light of the store's $90,000 annual shrinkage.

The detection equipment costs $30,000 to install and $5,000 per year to operate. Subtracted from the cost of the store's problem, this yields a positive return of $20,000 the first year and $50,000 in subsequent years. Over the first three years, the lost opportunity is $40,000 per year.

As you can see, we develop the data used to determine costs the same way we explore problems - through the process of diagnostic questioning. The answers to our questions tell us whether our customers have the resources and willingness to solve their problems. More importantly, the process of answering questions allows our customers to reach their own conclusions in their own time. Further, the fact that the customer provides the data enhances the credibility of the cost conclusions that result. This creates a high level of buy-in. It is also more compelling and accurate than the generic cost/return formulas and average industry costs that we so often find in conventional sales presentations.

Remember, it is the responsibility of the sales professional to develop the "cost of the problem" formula. It is a critical component of the quality decision process that they bring to their customer. The customer does not have the expertise or the inclination to put such a formula together. It will provide you with a key differentiator.

The final element of the Diagnose phase is to determine the problem's priority in the customer's mind. This is one crucial test of the significance of a problem's consequences that salespeople often overlook. The fact that a problem's costs are substantial in the salesperson's eyes does not guarantee that the customer feels the same way or will attempt to resolve it.

First, the cost may be an accepted part of doing business. A retail chain includes a line item for inventory shrinkage in its annual budget; a manufacturing plant considers some level of defects acceptable. Unless the cost exceeds acceptable levels, salespeople may well find that the customer will not feel the need to make a decision to change.

Second, even when costs do exceed acceptable levels, they must still be compelling in light of the other critical issues vying for the resources of the organization. If, for example, a customer is confronting a shrinking market for the goods or services the salesperson's offerings address and, as a result, has decided to leave that business, there is little reason to invest additional resources no matter how compelling the cost savings.

This is why it is so important to ask the customer to prioritize the problem and its costs before moving out of the Diagnose phase of the sale process. Again, this information is developed by asking questions, such as conversation expanders (see Figure 5.3).

Cost Quantification

Have you had a chance to put a number on ... ?

What does your experience tell you ... is costing?

Can you give a ball park number as to what ... costs?

Cost Prioritization

How does ... compare to other issues you are dealing with?

Does it make sense to go after a solution to ... at this time?

When you consider all the other issues on your desk, where does ... fall?

Figure 5.3: Conversation Expanders - Cost of the Problem

The Buying Decision

The Diagnose phase is now complete. In summary:

As salespeople, we have helped customers to realize that they have a problem that is seriously affecting their personal and/or business objectives.

With our assistance, the customer has thoroughly explored the dimensions of the problem and assigned a total cost to it.

The customer has determined whether that cost justifies immediate action relative to other issues and opportunities they face.

If we are still in the room at this point in the engagement, it is for one reason only: The customer has made the decision to buy.

We have not made a sales presentation. In fact, we haven't devoted any significant time to describing our solutions at all.

We haven't exerted any pressure on the customer whatsoever. Nevertheless, the customer has decided there is a problem that is costing more than he or she is willing to absorb and that we, the salespeople, understand the situation.

It is very important to recognize:

You don't need to have a solution to have a problem and

You don't need to have a solution to diagnose a problem.

Introducing solutions too early will frequently diffuse the decision process and distract from a clear diagnosis. One of the keys to managing the decision process is staying true to the decision at hand.

We have the inside track on this sale.

How did this happen? It resulted from a simple, logical change progression that has taken place in the customer's mind:

There is a problem.

It costs a fixed amount of money to leave it unattended.

That amount of money is significant enough to act on.

That decision to act is the decision to solve the problem or, more directly, the decision to buy a solution.

At the same time customers are reaching the critical stage in the change progression, salespeople have been establishing their own value in the customer's eyes. They have earned the customer's professional respect because of their ability to conduct a high-quality diagnosis. The customer's trust is gained because of the salesperson's willingness to end the engagement at any time the diagnosis revealed that a problem did not exist or was not worth acting on. The salesperson has created exceptional credibility by demonstrating an in-depth understanding of the customer's business. Now that the customer has made the decision to change, who do you think the customer believes is best qualified to help design a high-quality solution to the problem?

Granted the customer may not openly announce their decision, but they will present a more open and trusting demeanor. Signs such as answering questions very openly and providing access to people and information will verify and back up the fact that the decision has been made.

The conventional salesperson believes the decision to buy is made much later, after a presentation and proposal. One of the most significant paradigm shifts of the sale process is that as you conduct a thorough diagnosis, and by the time your customer has made the four elemental decisions of the Diagnose phase, it is highly likely that the customer has already made their decision to change and to change what they will buy. Since you have established exceptional credibility, it is highly likely they have decided to buy from you and your company.

If you grab hold of this idea, and it is well-supported by our research, it will provide a profound change to your business. Your days of pre-mature presentations will be over, and your proposal conversion ratio will increase dramatically.