Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 3: A Proven Method for Enterprise Sales

Overview

You're Either Part of Your System or Somebody Else's

A theory that explains how to sell, or explains anything else for that matter, is a product of abstract reasoning. It is someone's speculation about the nature of an activity or process. A theory may or, as is too often the case, may not be an accurate reflection of its subject's true nature. What grounds a theory and makes it worth adopting and emulating is that it works in everyday practice in the real world. That's why we shadow sales professionals with successful track records in enterprise sales.

Clients ask us to research and explain what makes their best salespeople excel. They request that we capture from their salespeople: What do they do? How do they think? What questions do they ask? What do they say to prospects and customers? How do they handle competitive threats? And when we've distilled it all down, the objective is to teach these best practices to the rest of their sales organization - to replicate the best of the best.

We have worked with customers' top salespeople as they call on their customers to identify the best enterprise sales practices. Accompanying high performers (the top 3 to 5 percent of salespeople) on thousands of appointments, we've watched them work, studied their reasoning and behavior patterns, and have come to understand the thinking and the methods behind their success.

We looked to the sciences of human behavior and interpersonal communication to explain why what we observed was working. In short, we reverse-engineered the success process. We observed what worked, sought out solid research to explain why, and evolved learning and performance development models to explain and teach the process to others.

Shadowing top-performing salespeople quickly led us to a surprising observation: Generally, the most successful don't rely on traditional selling techniques. When we accompany the best of the best on calls, we find that they are not offering their companies' sales brochures. They don't recite prepared pitches chapter and verse, nor do they seem to steer the conversation or lead the customer in any overt manner. We discuss what is going on later, but for now, let's just say that top performers are not selling ... at least, not in the conventional sense.

The success of top performers is often a mystery to their employers and their colleagues. They are considered anomalies - rare exceptions to the rule whose success is a natural, but irreproducible, phenomenon. This is compounded by the fact that many top performers can't clearly articulate the reasons behind their own success and rarely follow their companies' standard sales processes. Here's how a typical conversation sounds:

We ask, "Was there a particular reason you didn't bring out the product brochures on this appointment?"

The answer comes back: "I don't know. They seem to distract the customer."

"In what way?"

"Well, it's too easy to start talking about the product and get a lot of questions."

"Is that a bad thing?"

"I guess not, but I know I don't get the information I need when I spend all my time talking about our products. I seem to be more effective when I leave the brochures in my office."

These top performers are not being cagey. Rather, they have developed a personal style of selling and a natural communication process through experience. It is often a long and painful period of trial-and-error experimentation. Once success is achieved, there is a tendency to suppress all the pain they went through to perfect the process. Now, they are too busy winning sales to spend time documenting what they are doing and analyzing how and why it works. They are seldom able to explain in a clear fashion why they do what they do and frequently respond: "It just seems to work," or "It felt like that was the right thing to say." Not very instructive. Nevertheless, their hard-won knowledge is an extraordinarily valuable resource as a sound basis for a model of sales excellence.

Over the years, we've worked very hard to translate those "seems" and "felt likes" into tangible and teachable elements. We've distilled the common attributes and behaviors of top performers into three primary areas. We've studied how these three areas connect to research and theories in organizational and behavioral psychology, decision theory, emotional intelligence, interpersonal dynamics, and change management. Based on that knowledge, we developed and refined a enterprise sales methodology, which is organized into three primary elements - systems, skills, and disciplines:

A system is a set procedure or organized process that leads to a consistent and predictable result. Systems are the processes that top performers follow to accomplish their goals and the procedures and tools that their organizations provide to support their efforts.

Skills are the content knowledge along with the physical and mental abilities that enable salespeople to execute the system. Skills are tools and techniques that top performers use to accomplish their goals.

Discipline is the mind-set of the professional. It is about attitude, standards of performance, and mental and emotional stamina. Disciplines of high-performing sales professionals are the mental and emotional attitudes with which professionals approach their work and the mental or emotional stamina that they draw on to consistently and successfully see it through.

Think of systems as the "what to do," the skills as the "how to," and discipline as the inner strength that supports the "will do."

The knowledge gained from shadowing top sales professionals is organized into these three areas for good reason. Systems, skills, and disciplines are the foundational elements and guiding principles of all professional bodies of knowledge. Professionals such as pilots, accountants, engineers, doctors, and lawyers are called on to learn, practice, and master these three areas. Pilots follow many systems to operate the planes they fly. They master physical and mental skills to execute those systems, and they embrace a discipline or mind-set that governs how they think about their work and provides the mental stamina to remain cool, calm, and collected while performing the critical task at hand. To be able to speak of selling as a profession, which is exactly what we consider it to be, we need to be able to define the systems, skills, and disciplines that must be adopted, consistently practiced, and mastered to achieve its fullest potential.

We begin defining a professional body of knowledge for winning the enterprise sale by describing the disciplines that top sales professionals bring to their jobs.

A Discipline for Enterprise Sales

The discipline with which top performing salespeople approach their work is perhaps the most critical component of their success. Just as the assumptions inherent in traditional sales methodology doom those who accept them to ineffectiveness and miscommunication, the mental framework with which we approach the enterprise sale acts as the enabler of all that follows. Mind-set is the starting gate of enterprise sales success. Without the mind-set or point of view, the best laid skills or tactics will fall flat on their face.

Three statements summarize, in broad terms, the discipline of enterprise sales:

The most successful people in enterprise sales recognize that for their customers, the process of buying goods and services is all about making a decision to change. When they are working with a customer, they are actually helping that customer navigate through the change process.

All too often, a sales professional uncovers a serious problem the customer is experiencing, which the customer agrees is a problem, and wants to solve. They have discussed the solution options, and the customer agrees that the solution can eliminate the problem, yet they do not buy. Why does this occur? It's not that the customer doesn't have a problem, and it's not that you don't have a solution. It occurs because the customer cannot or will not go through the personal or organizational changes needed to implement the solution.

Every purchase is based on a customer's decision to change. In simple sales, the customer's decision and the change process is often transparent, but it does take place. At a most elemental level, even a purchase of paper for the copy machine involves a degree of change. "I notice we're out of paper; call my supplier or go to the Web and order the paper and restock the cabinet." The decision was simple - a repeat purchase and not much thought needed to go into it. No muss, no fuss. However, change did take place. I went from no paper to ample supply, I'm more relaxed about the upcoming reports to be copied and distributed, and my bank balance or available budget dropped by a few dollars.

In simple sales, a salesperson can ignore customers' change process, comfortable that customers will navigate the elements of change on their own. Elements of the decision and changes involved with the purchase are clear to the customer. Thus, the customer understands the risk involved in the change, and resistance to making the change is low. But what happens when the complexity of the sale increases in a business-to-business transaction? The decision elements of the situation and the changes involved in the purchase are more complicated and more difficult to understand. The risk of changing is higher. The investment, the requirements of implementation, and the emotional elements - the impact on the buyer's career and livelihood - all create a higher risk of change. Accordingly, resistance to change is substantially higher. Change and risk management now play a major role in the decision and subsequent sale.

The more complicated a sale becomes, the more radical the change the customer must undertake and the greater the perceived, as well as actual, risk. A conventional salesperson, who is solely focused on presenting and selling his or her solutions, is ignoring the critical elements of decision, risk, and change in the enterprise sale. The most successful salespeople, on the other hand, are noted for their ability to understand and guide the customer's change progression (see Figure 3.1).

There is a large body of psychological and organizational research concerning the dynamics of change. A key insight is that the decision to change is usually made as a response to negative situations and, thus, is driven by negative emotions. People change when they feel dissatisfied, fearful, and/or pressured by their current problems. Similarly, customers are more likely to buy in those same circumstances. Conversely, people who are satisfied with their current situation are unlikely to change and are unlikely to buy.

The best salespeople understand that all customers are located somewhere along a change spectrum. They work with customers to identify and understand their areas of dissatisfaction, to quantify the dollar impact of the absence of a solution, and to design the optimum solution.

What happens when salespeople ignore the Progression to Change (see Table 3.1)? Here is a common scenario: The salesperson focuses on selling the future benefits of his offering. He does a wonderful job presenting, eventually lifting the customer to a euphoric peak with his exciting and unique solution. It is the perfect time to close and, of course, that is exactly what our salesperson attempts to do. What happens next? The customer, being asked to commit, is literally shocked out of his gaze into the utopian future and confronted with the current reality of all the risks and issues of change. Then come the objections, and the resistance to change rears its ugly head. The sales process slows down, and the sale, which the salesperson thought was "in the bag," is in serious jeopardy of being lost.

Table 3.1: Progression to Change

|

Satisfied |

"Life is great!" Customers have strong feelings of success. They feel their situation is very good and see no need to change. |

|

Neutral |

"I'm comfortable." Customers have no conscious feelings of satisfaction or pain. They are not actively exploring their problems; they are not considering change. |

|

Aware |

"It could happen to me." Customers have some discomfort. They understand that a problem exists and that they may have some exposure, but it is not directly connected to their situations. They may consider change in the future. |

|

Concerned |

"It is happening to me." Customers see the symptoms of the problem. They recognize that they are experiencing the problem and that it is potentially harmful. They are ready to define and explore the problem. |

|

Critical |

"It is costing xxx dollars." Customers have a clear picture of the problem. They are ready to quantify its financial impact." |

|

Crisis |

"I must change!" Customers recognize that the cost of the problem is unacceptable and that they can no longer avoid change. They have reached the point at which the decision to change is made." |

When salespeople approach the sales process from a risk and change perspective, they deal directly, and in real time, with the critical change and risk issues that their customers must resolve. Instead of selling a rosy future, they focus on helping their customers identify the consequences of staying the same or not changing the negative present. When they help customers understand the risks of staying the same and specific financial costs or lost revenues related to staying the same, the decision to buy (change) takes on a compelling urgency. They are not dealing with an optional future but with the immediate reality of a problem that they must solve. Understanding and focusing on the customer's decision to change also give the salesperson a distinct advantage and a unique position in the marketplace.

Typically, there are two processes at work in a sale: (1) the customer's buying process, which is primarily designed to obtain the best (lowest) price, and (2) the vendor's selling process, which is designed to move products and services at the best (highest) price. These processes, with their conflicting agendas, naturally generate tension and mistrust.

When we work with the customer from the perspective of a decision to change, we set aside these conflicting agendas. Now both salesperson and customer work toward a mutual objective - understanding the customer's problem and aligning the best available solution so that the customer can make the highest quality decision about the proposed change.

The second focus of the most successful salespeople is on business development. That is, successful salespeople think more like business owners than like salespeople. We call it business think.

Suggesting to salespeople that they need to be concerned with the development of their customers' business brings obvious agreement. "Yes, of course," they say, "we do that." But the paradigm from which most operate becomes very clear when we ask them what happens after the customer agrees to buy. The typical answers include "coordinating the installation," "getting paid," and "training the customer." The interesting thing about these responses is that they are primarily focused on what happens to the salesperson. The business being developed is the salesperson's, not the customer's.

No matter how much lip service conventional salespeople pay to developing their customer's business, they are not fooling the customer. Today's customers are forcing vendors to take an active role in their business success. Tighter supply chain management and preferred supplier programs reward sellers who help develop their customers' businesses. Those who adhere to traditional sales practices are left out in the cold. Smart professionals know that focusing on the success of the customer will ultimately improve and enrich their own business.

When we ask the best salespeople what happens after the customer agrees to buy, they say, "We help them accomplish their business objective" or "The customer will realize x dollars in reduced costs or increased revenues." The business they are developing is their customer's business.

The point is that the answers to the question need to be a balance of items that happen to the customer's business as well as items that occur in the seller's business. Seldom do we hear comments on what happens in our customer's business.

Business think means that we take the time to understand the financial, qualitative, and competitive business drivers at work in our customers' companies. It means that we frame our communication with customers in terms that they understand and that matter to them. Finally, it means that when we have delivered our solutions, we measure and evaluate success from our customers' perspective.

Business think also has profound implications for how salespeople perceive themselves. When you approach your work as a business enterprise, you quickly realize that resources are limited and must be focused to achieve their greatest potential. You know that you can't be all things to all customers and devote your energy only to the best opportunities available. You come to respect your own time and expertise as valuable resources and expect your customers to do the same.

Successful salespeople do not waste time in situations where their solutions are not required. It is also why they tend to gravitate toward the opportunities where their services are most needed and highly valued.

We describe the behavior that results from this mindset as "going for the no." It is a mind-set that believes that at any given time, a small percentage of the marketplace will buy; therefore, we must quickly identify those that won't and set them aside for later attention. Compare this attitude to that of conventional salespeople who are taught to always be "going for the yes." They allocate their time equally among the entire universe of opportunities, and when they get in front of potential customers, they stay there until the customers disqualify them. They aren't treating their own time and expertise with respect, and it shouldn't come as much of a surprise when their customers don't either.

To succeed in enterprise sales, the most successful salespeople are interacting with their customers by building relationships based on professionalism, trust, and cooperation.

You could argue that all salespeople are working toward that same goal, but while that may be true in theory, it has not been translated into reality in the customer's world. In the mid-2000s, researchers asked almost 3,000 decision makers "What is the highest degree to which you trust any of the salespeople you bought from in the previous 24 months?" Only 4 percent of those surveyed said that they "completely" trusted the salespeople from whom they had bought. Nine percent said that they "substantially or generally" trusted the salesperson. Another 26 percent said they "somewhat or slightly" trusted the salesperson, and 61 percent said they trusted the salesperson "rarely or not at all." [1] Remember, these are the responses of customers about the salesperson from whom they decided to buy! What did the respondents think of the salespeople from whom they decided not to buy?

As we have already seen, this negative perception of salespeople is a problem inherent in the conventional sales process. Accordingly, the only sure way to break through the interpersonal barriers between salespeople and customers is to abandon conventional sales models. The most successful salespeople do not model typical sales behavior. The models that best reflect desired professional sales behavior are the doctor, the best friend, and the detective.

The Doctor

Doctors provide a model for professionalism that salespeople can relate to and emulate. Even though the medical profession today has its own image problems, let's consider it in a general sense - the medical profession at its best.

Doctors take an oath to "do no harm"; that is, do their best to leave patients in better condition than they find them. They accomplish this goal through the process of individual diagnosis. Picture a middle-age, overweight male walking into a doctor's office. Does the doctor observe the patient's appearance, note that he is a "qualified" candidate for a bypass, and recommend surgery? Of course not; it would be absurd. Doctors recognize that no medical solution is right for every patient and that they cannot diagnose patients en masse.

In contrast, salespeople regularly walk up to customers and prescribe solutions despite the fact that many of those customers may fit the profile only for the solutions in the most superficial way. The best salespeople, like doctors, diagnose each customer's condition individually and prescribe solutions that fit the unique circumstances of each case. Accordingly, their customers see them as professionals who are willing to take the time to understand their problems and can be trusted to offer solutions that not only "do no harm," but also improve the health of their businesses.

The Best Friend

When we say the best salespeople act like their customers' best friends, we don't mean that they get invited to backyard barbecues and family gatherings. Best friends are often our favorite companions, but they embody other qualities as well. Picture the most trusted person in your life - a spouse, parent, colleague, teacher, coach, or advisor. That is the relationship model we call the best friend model.

We expect our best friends to look out for our best interests. They help to protect us from errors in judgment. We also look to our best friends for honest opinions and answers. We trust them to tell us the truth. The best salespeople use the role of best friend as a litmus test. They ask themselves, "If this customer were my best friend, what would I advise in this situation?" When it comes time to offer solutions, they ask, "Is this the answer I would propose if this customer were my best friend? Do I have his best interests in mind or my own?"

The Detective

The third role that successful salespeople model is one of personal style and interpersonal process. In an old television series, actor Peter Falk convincingly played Detective Columbo - an unusual kind of detective. He never threatened a suspect. In fact, he rarely even raised his voice. Columbo was mild-mannered and nonthreatening to the point of appearing ineffective. In fact, the show's criminals consistently underestimated this detective - at least in the early stages of the investigation. It was a natural mistake. Columbo made them feel safe and secure, and while they congratulated themselves on their craftiness, the detective quietly went about the business of diagnosing the situation and reconstructing the crime.

Amazingly, Columbo solved every crime he ever investigated (television series aren't exactly real life scenarios). He accomplished this feat in two ways: by observing the most minute details of the crime scene and by asking a seemingly endless number of polite, unassuming questions. By the way, Columbo's methods provide an excellent contrast to James Bond's. Bond, examined in the prior chapter, already knows all the answers, so he doesn't need to ask any questions. All that he needs to do is verbally challenge and strong-arm the villain.

As salespeople, we need to emulate the detective. We need to fully understand what is happening in our customer's world. We can accomplish this goal in the same non-confrontational way that Columbo solved crimes, through the power of observation and the process of questioning and clarifying the things that we see. In The Trusted Advisor, David Maister devotes a full chapter to the effectiveness of the Columbo model. He also notes, the main barrier to using this effective model is our own emotional need to be the center of attention.

[1]The findings of the sales survey are recorded in, You're Working Too Hard to Make the Sale (Irwin), p. 16.

A Set of Skills for Enterprise Sales

The second element of any profession encompasses the skills and tools that its practitioners use to achieve their goals. Skills, as defined earlier, are the mental and physical ability to manipulate the tools that professionals use to execute systems.

In a enterprise sales process, the most successful salespeople are capable of using a large number of tools. Most of these are specific to certain elements of the sales process, and we discuss them in later chapters. Three major tools span the entire selling process and, as such, are best introduced before we describe the process itself.

These three tools help us answer one of the basic questions present in every enterprise sale: Who should be involved in decisions determining the problem, the design, and the implementation of the solution? What are the problems that the customer is actually experiencing? How are those problems impeding the customers' ability to accomplish their business objectives? How are those problems connected to the salesperson's solutions? How will successful business outcomes be achieved for the customer? The answers to these questions represent an equation we need to solve to successfully navigate a enterprise sale:

Right People - The Cast of Characters

It follows that if customers do not have a quality decision process, it is not likely they would assemble the best group of people to be involved in the decision. In the enterprise decision, the search for the elusive, single decision maker is futile. There is always the individual who can say no, even if everyone else says yes, and that same individual can say yes when everyone else is saying no. Reality shows that today's enterprise decisions are far more likely to evolve from a group initiative and consensus. Smart business executives realize that successful implementation is directly related to the degree of buy-in. This fact does not alleviate the need to find decision makers; it actually raises that task to a more sophisticated level.

One telling observation from the field is that when it comes to identifying and interacting with decision makers in a enterprise sale, the most successful salespeople don't take the hand that is dealt them. They don't accept the decision makers identified by their customers without question. Rather, they understand that customers who do not have a quality decision process in place are unlikely to be able to assemble an effective and efficient decision-making team. As a result, successful sales professionals take an active role in building the optimal "cast" for their customers. They seek to identify the important cast members in the customer's organization, involve each in the decision process, and ensure that each has all the assistance required to comprehend the problem, the opportunity, and the solution. Effectively managing the decision team is a job that spans the entire enterprise sales process. We call the tool used to achieve that task the cast of characters, and it helps us identify and access the right people.

The key to casting a enterprise sale is perspective. The cast of a enterprise sale needs to include a set of players that encompasses each of the perspectives required in a quality decision. In every sale, there are two major perspectives: The problem perspective includes members of the customer's organization who can help identify, understand, and communicate the details and cost of the problem. The solution perspective includes those who can help identify, understand, and communicate the appropriate design, investment, and measurement criteria of the solution.

Casting doesn't stop here. We also need decision team members who can bring the perspectives available at different levels of the organization to the table. For both the problem and the solution perspectives, we need to include individuals, internal and external, who represent and/or advise the executive, managerial, and operational levels of the customer's organization.

Why go through all this work? The obvious answer is that there is no other way to ensure that you are developing all of the information needed to guide your customer to a high-quality decision. There are also some less obvious answers. For instance, would you prefer to present a solution to a group that has had little or no input into its content, or would you rather present a solution proposal to a group that has already taken an active role in creating it? Would you prefer to deal with a newly installed decision maker who has replaced your single contact in the middle of the sales process, or would you rather face that new decision maker with the support of all the remaining cast members and with full documentation of the progress already made?

The answers to these questions are clear. The successful sales professional casts the enterprise sale to assemble the group of players who has the most impact, information, insight, and influence on the decision to buy. This shortens the sales cycle by effectively reaching the right people and helping them make high-quality decisions. You build predictability into your sales results and ultimately shorten the sales cycle time.

Right Questions - Diagnostic Questions

All salespeople are taught to use questions in the sales process, but most use questions in ineffective ways and in dubious pursuits. They ask questions to get their customers to volunteer information they have been taught is critical to the sale. Their goal is to identify who makes the decision to buy and to determine how much the customer is willing to spend on a solution. They want to maximize their contact with customers and get customers to pinpoint their own problems. All of these reasons subvert the most valuable use of questions - to diagnose.

The most successful salespeople are sophisticated diagnosticians. They understand that to effectively and accurately diagnose a customer's situation, they must be able to create a conversational flow designed to ask the right people the right questions. They also know that they gain more credibility through the questions they ask their customers than anything they can ever tell them.

The "right questions" refers to four types of diagnostic questions that salespeople use to understand and communicate customers' problems:

A to Z questions frame a customer process and then ask customers to pinpoint specific areas of concern within it.

Indicator questions uncover observable symptoms of problems.

Assumptive questions expand the customer's comprehension of the problem in nonthreatening ways.

Rule of Two questions help identify preferred alternatives or respond to negative issues by giving the customer permission to be honest, without fear of retribution from the salesperson.

These diagnostic questions, which we detail in the chapters that follow, are purposely designed to avoid turning conversations into interrogations, or rote interviews and surveys. Instead, they help salespeople develop integrated conversations, in which the customer's self-esteem is protected, mutual value is generated, and communication is stimulated. (Silence and listening skills, as we describe later, also play important ancillary roles in diagnostic questioning.)

Right Sequence - The Bridge to Change

Just as enterprise sales feature multiple decision makers, they also require multiple decisions. The content and sequencing of those decisions is what allows us to connect our customers and the problems they face to the solutions that we are offering. To accomplish this goal, we need to establish an ordered, repeatable sequence of questions that will lead to a high-quality decision.

This sequence is called the bridge to change and is patterned after the methods physicians are taught to diagnose complicated medical conditions and prescribe appropriate solutions (see Figure 3.2). It guides salespeople by establishing a questioning flow capable of leading their customers through enterprise decisions. More importantly, it allows salespeople to pinpoint the areas in which they can construct value connections that will benefit their customers.

The bridge has nine main links; each is a potential area for creating and capturing value. It starts at the organizational level by examining the customer's major business objectives or drivers and the critical success factors (CSFs) that must be attained to achieve those objectives. It seeks to identify the individuals responsible for each CSF and to understand their personal performance objectives. The bridge prompts the salesperson to identify performance gaps by identifying potential shortfalls in the customer's key performance indicators, probing for their symptoms, uncovering their causes, and quantifying their consequences. In its last links, the bridge helps define the expectations and alternatives for solving the customer's problems and then narrows the search to a final solution.

The bridge to change functions like a decision tree. Each branch of the tree is integral to a quality decision. Each link logically connects to the next, and although we can travel several branches simultaneously, none can be skipped without disrupting the decision process and, of course, the potential sale. In fact, when you hear customer objections, what you are actually hearing is the direct result of a skipped or less-than-fully traveled branch. If each branch has been completed to a customer's satisfaction, all of their potential objections have, by definition, already been resolved. The customer can, of course, still refuse to buy, but it is unlikely that their refusal will be based on any reason within the salesperson's control.

The three tools - cast of characters, diagnostic questions, and the bridge to change - and the ability to consistently use them, represent the key skills of a diagnostic sales professional. They also represent the three components of the enterprise sales equation - right people, right questions, and right sequence.

A System for Enterprise Sales

The final element in the foundation of a profession is its system. A system, in this broad sense, is an organized process and set procedures that lead to a predictable result. Our approach is based on observations of successful sales professionals.

This approach offers us a platform on which to understand and integrate our professional skills. This represents a quantum leap beyond typical sales training, which is usually skill-based and which leaves salespeople with a briefcase full of tools, but no systematic way to apply them to achieve their ultimate goal.

Our method is a metaprocess, one that can be overlaid on any enterprise sale. It provides a navigable path from the first step of identifying potential customers, through the sale itself and onto expanding and retaining profitable customer relationships. It is a system that encompasses all of the critical activities of the sales professional and provides the decision-making assistance that customers involved in a tricky business decision so desperately need.

As we see in Chapter 9, it is also an extended process that ranges from product inception to customer consumption. It can be used to enhance the communication and integration between major business functions, from product development to marketing, to sales, service, and support.

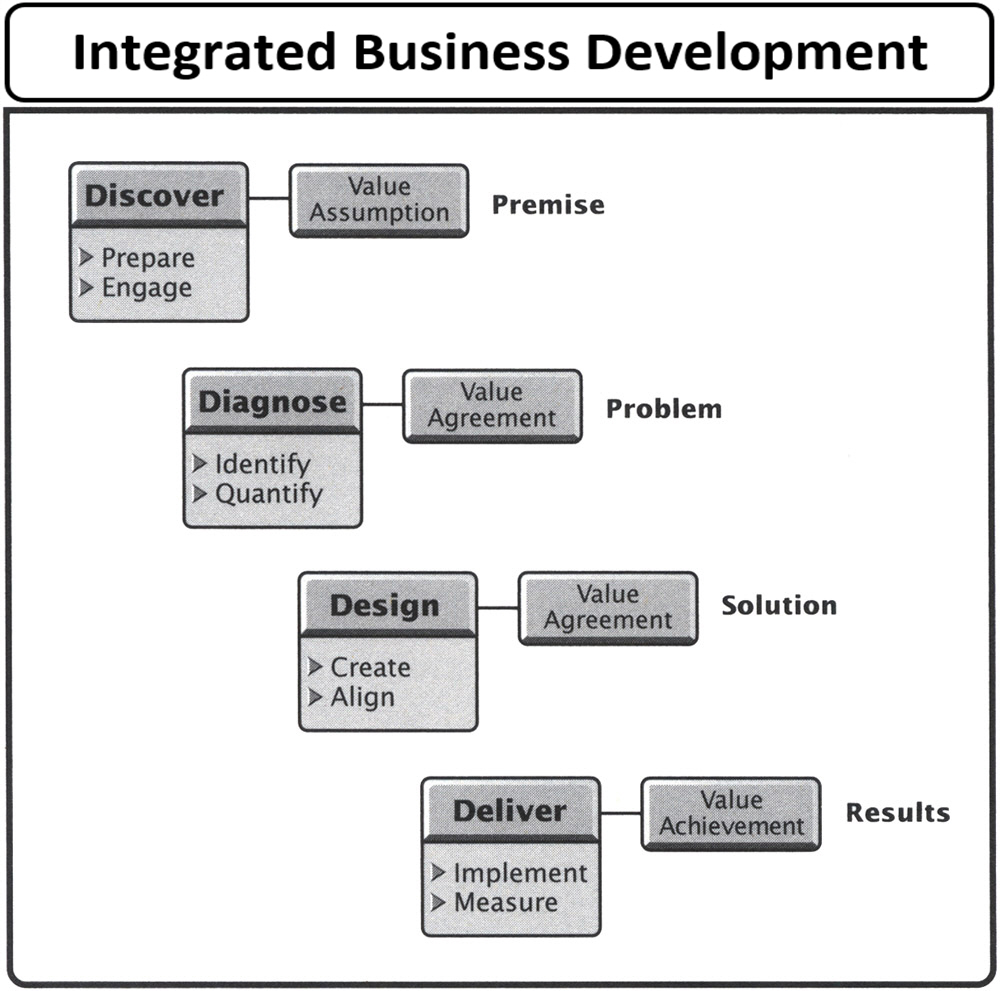

Because this method covers the entire profession of enterprise selling, it naturally encompasses a great deal of information. To facilitate comprehension and ease of use, we divided the process into four subsystems or phases. The phases of the process are related in a linear fashion and are organized by the major activity that is undertaken in each specific phase. They are Discover, Diagnose, Design, and Deliver (see Figure 3.3).

Discover

Discover is about research and preparation. It encompasses how salespeople get ready to engage and serve customers. Everyone who sells starts at the same point - the identification of a customer. In conventional sales, this is called prospecting and qualification, which, unfortunately, is often characterized by minimal preparation. In Discover, however, we expand the preparation into a process, which is aimed at the identification of a specific customer who has the highest probability of change.

Discover means pushing beyond the traditional boundaries of prospecting to create a solid foundation on which to build a long-term, profitable relationship. It recognizes the fact that every qualified prospect will not become a customer. It embraces that realization by actively looking for reasons to disqualify a prospect and by refusing to unnecessarily waste the time and resources of the prospect or the sales professional.

The tasks in the Discover process include precontact research of potential customers and their industry. Discover also includes the preparation of an engagement strategy, which includes an introduction, some basic assumptions about the value that could be created, and a conversational bridge designed for that specific customer. In addition, it includes the initial contact with the prospective customer, during which this information is communicated. Customer and salesperson mutually decide whether the sales process should continue.

In the Discover phase, as in each succeeding phase of this process, salespeople are actively building a perception of themselves in the customer's mind. In this case, that perception is one of professionalism. We want customers to understand that mutual respect and trust govern our relationship. We want them to see us as competent, well versed in their business, and a source of competitive advantage.

Diagnose

The Diagnose stage encompasses how salespeople help their prospects and customers fully comprehend the inefficiencies and performance gaps. It is a process of hyperqualification during which we pursue an in-depth determination of the extent and financial impact of their problems.

Most selling methodologies recognize the importance of understanding customers' problems and, accordingly, often tack some form of needs analysis onto their process. However, the true intention of needs analysis is usually subverted. First, we find that it is used to get the customer to make observations and reach conclusions. In essence, customers are asked to diagnose themselves: What are your issues and what are you looking for? Second, the questions salespeople ask their customers are more often about the customer's buying process than their situation: What are you looking for, who will make the decision, when will you make the decision, how much do you want to spend? Finally, and in the worst cases, needs analysis is used as a highly biased review to justify the salesperson's solutions.

With our method, diagnosis is not subordinate to solutions or the sale. It is meant to maximize customers' objective awareness of their dissatisfaction, whether that dissatisfaction supports the salesperson's offerings or not.

In the Diagnose phase, the process most radically diverges from conventional selling. Our research tells us that during a well-executed diagnostic process, the customer makes the decision to buy and from whom to buy. In the more traditional approach, salespeople are looking for this decision after the presentation and during "the close." Therefore, in the Diagnose phase, the most critical elements of the enterprise sale occur.

The salesperson's tasks during the Diagnose phase begin when we shift the emphasis of our fact finding to focusing on the customer's internal issues. At this point, we need to deepen our understanding of our customers' business, their job responsibilities, perspectives, and concerns. Diagnosis also includes measuring the assumptions about customers' problems that we presented in the Discover phase against the reality of the situation and quantifying the actual cost of the problem. It includes a collaborative effort to evolve a comprehensive view of the problem to customers, thus allowing them to make an informed decision as to whether they need to change.

In the Diagnose phase, we want our customers to perceive us as credible. We establish our credibility by our ability to identify, evaluate, and communicate the sources and intensity of their problems, as well as helping them recognize opportunities they are not aware of. We reinforce that credibility by refusing to alter the customer's reality to fit our own needs.

Design

Design encompasses how salespeople help the customer create and understand the solution. It is a collaborative and highly interactive effort to help customers sort through their expectations and alternatives to arrive at an optimal solution.

In a more conventional sales approach, design equals presentation, and, in presentation, the customer is not involved in the design of the solution. As a result, they do not develop a significant degree of ownership of that solution. The conventional salesperson may say, "This is the product we offer that is best suited to your situation." Then they proceed to reel off a litany of features and technical information specific to that solution.

In our process, however, the Design phase is not focused on a specific solution. Its goal is to get salespeople and customers working together to identify the optimal solution to the problems that were uncovered and quantified in the Diagnose phase.

There is an important distinction here. An optimal solution does not mean the product or service that we are charged with selling right now is best suited to the customer's problem. Rather, the optimal solution is a series of product or service parameters that minimizes the customer's risk of change and optimizes return on investment. By staying true to the objective of a quality business decision, where that solution will be found is a secondary consideration at this stage in the decision process.

The tasks included in the Design phase are aimed at establishing and understanding the decision criteria the customer will use to find a solution to the problem. This aim requires us to establish the solution results the customer would expect, the quantifiable business values for those outcomes (and thus, the available funding for the acquisition of the solution), and the timing in which it must be delivered. We manage customer expectations during the Design process by introducing and exploring alternatives, including solutions offered by competitors. We also teach customers the questions they should be asking of all potential suppliers to assure their quality decision.

In the Design phase, we want our customers to perceive a high degree of integrity in all our behaviors. We establish our integrity by creating a solution framework that best solves their problems. It frames a set of decision criteria that we would use to determine what to select for ourselves or would recommend without hesitating, if our best friends were experiencing this particular problem. The conclusion of the Design phase is what we call a discussion document. This document provides a summary of the diagnosis with a "pencil sketch" of the solution. It is used to do a final sanity check before completing a formal proposal and presentation. It is the dress rehearsal, your final run through, and it assures there will be no surprises during the final presentation.

Deliver

In the final phase of the process, the work of the previous phases comes to fruition. It encompasses how the salesperson assures the customer's success in executing the solution.

While the conventional sales process forces salespeople to overcome objections and try to close the sale, the diagnostic approach allows customers to evolve their own decisions. Customers who have traveled through this process have a clear understanding of their problems, and they know what the best solution will look like. In fact, they are coauthors of that solution. Salespeople who use this process and have not disqualified the customer by this point in the process experience exceptional conversion ratios. That is why we say that the ultimate goal in the Deliver phase is to maximize the customer's awareness of the value derived from the solution that is being implemented.

The tasks in the Deliver phase begin with the preparation and presentation of a formal proposal and the customer's official acceptance of the solution. The next steps include the delivery and support of the solution and the measurement and evaluation of the results that have been delivered. The final task of the Deliver phase is the maintenance and growth of our relationship with the customer.

In the Deliver phase, we want our customers to perceive us as dependable. We literally do what we said we were going to do. As we complete the sale, our customers should be thinking: You are there for me; you will take care of me; I can depend on you.

The four phases of this method represent a reengineering of the conventional sales process. The process eliminates the inherent flaws in conventional sales processes and directly addresses the challenges that salespeople face while trying to master enterprise sales in today's marketplace.

Creating Value through The Business Development Method

Value is a critical concept that no salesperson can afford to ignore. Value can be defined as incremental results the customer is willing to pay for. To successfully complete a sale, salespeople know that they must be able to create value for their customers and they must be able to capture a reasonable share of that value for their company.

Most salespeople are unable to manage the challenge of creating and capturing value for two reasons:

The increasing commoditization of their offerings renders their ability to communicate that value to customers ineffective.

The increasing complexity of problems and solutions makes it ever more difficult for customers to comprehend the true value of their solutions when that value is present.

Even when their managers instruct them to create and capture value, they are rarely told how to accomplish this feat. As a result, value creation is more of a buzzword than a tangible reality.

This process offers a two-part answer to that dilemma. First, it is a unique value-based process that is connected to value in a lock-step progression. Thus, as you complete each of the four phases of the process, your customer is one step further along the path to attaining value.

We all approach our work from a value proposition established in our companies. These propositions, which are usually stated in the most general terms, define the markets addressed by our solutions and identify the potential value our solutions offer that group of customers. The guidance provided by value propositions gives us a platform from which we can undertake the Discover phase of the process.

In discovery, we identify a prospective customer and refine our value proposition in the specific terms of that customer's likely business situation, problems, and objectives. We literally tailor the value proposition so it fits a single customer. We call this version of the value proposition a value assumption (see Figure 3.4). The value assumption is a hypothesis as to the value we believe we could bring to this specific customer. The key point is we are not making a boastful claim; we are discussing possibilities.

In turn, a value assumption becomes the premise for the diagnosis. In the Diagnose phase, we further develop and test the assumptions we have made about the definition and scope of the customer's situation. We determine to what degree our assumptions are correct; that is, the symptoms and indicators are occurring in the customer's business. We identify and quantify the impact of the absence of our value. To the degree the assumptions are correct and the customer agrees with us, we have the beginnings of value agreement with the customer on the dimensions of the problem.

We continue the evolution of the value agreement during the Design phase. The objective of the Design phase is to collaborate with the customer to create a solution that is aligned with the issues and expectations of the customer. The outcome of the Design phase is a value agreement with the customer on the dimensions of the value our solution will bring to the customer.

With a complete value agreement defined, we can move to the final step of our process - Deliver. In the Deliver phase, we implement the solution and measure results. Delivering value to the customer is the ultimate and highest goal of salespeople: value achievement for our customers and ourselves. The integrated process is shown in Figure 3.3.

Second, this process enables sales professionals to leverage the value they deliver to customers at three levels. In ascending order of complexity, profitable return, and competitive advantage, these are the Product, Process, and Performance levels of value.

At the Product level, the value focus is on the product or service itself. Product quality, availability, and cost are the major sources of value at this level. Typically, the salesperson is dealing with purchasing and competing with like products and services.

Conventional sales strategies are limited to the leverage of value at the Product level. They make only the most tenuous connection with the customer. Thus, in their customers' eyes, this is a commodity sale, subject to the price pressures we have already described.

At the Process level, the delivery of value is expanded from the product (or service) being sold to the process in which the customer will use it. The optimization of the process becomes the major source of value at this level. Typically, the salesperson and his team are working with operating managers in the various departments at a tactical level. The sale itself becomes an integral part of a process improvement effort.

At the Process level of value, sales professionals are creating a limited partnership with the customer. In their customers' eyes, this sale delivers a greater degree of value than a commodity-based transaction, but the relationship has shallow roots. It can easily lose its value for the customer when the process is optimized or if the process becomes outmoded or is eliminated.

The Performance level offers the greatest potential for value leverage and it is the highest value level which a sales professional can achieve. The development of the customer's business becomes the major source of value at this level. Typically, the sales professional is working with senior executives, as well as the operations level, and the sale is only one manifestation of an ongoing relationship that is connected to the organization at an enterprise level.

As sales professionals are creating and capturing the optimal value at the Product and Process levels; their ultimate objective is to reach the Performance level. At this level, they create strategic partnerships with their customers. In their customers' eyes, the sale is an investment in a more profitable future and the relationship with the seller is a valuable asset. Relationships like this are not easily uprooted. (The relationship among the three levels of value is shown in Figure 3.5.)

In terms of value leverage, it is important to note that we define customers in a broad sense that includes all sales channels. For instance, if you are delivering products and services through a distribution network or channel partners, you should be considering how to enhance each of their businesses, as well as your end-users' businesses, at the Product, Process, and Performance levels.

In this chapter, we introduced the systems, skills, and disciplines behind controlling the enterprise sale. In the next four chapters, we show each phase of the process in greater detail to help you better understand how the major elements of the enterprise sale operate in practice and to help you get the results you are looking for.